CHAPTER 1:

PRIMARY EDUCATION

CLOSING

THE GAP

A young Burundian refugee learns Kirundi at Jugudi primary school in Nyarugusu refugee camp, Tanzania. There are only 31 teachers for over 1,100 primary-age children in the school. © UNHCR/FARHA BHOYROO

Millions of refugee children and youth are missing out on a fundamental human right: the right to a quality education.

Today, there are around 3.7 million refugee children out of school – more than half of the 7.1 million school-age refugee children.

Despite major investment in primary education, the inexorable rise in forced displacement around the world – including refugees, asylum-seekers, people displaced within their own borders and the stateless – means there are big gaps between refugees and their non-refugee peers when it comes to access to education[1].

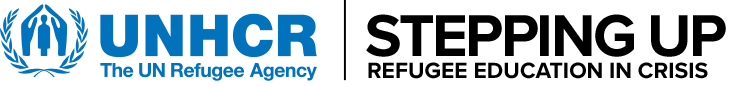

At primary level, the number of refugee children enrolled in school in 2018 was 63 per cent, up two percentage points on the previous year. That compares with a global figure for all children of 91 per cent.

Turning the tide

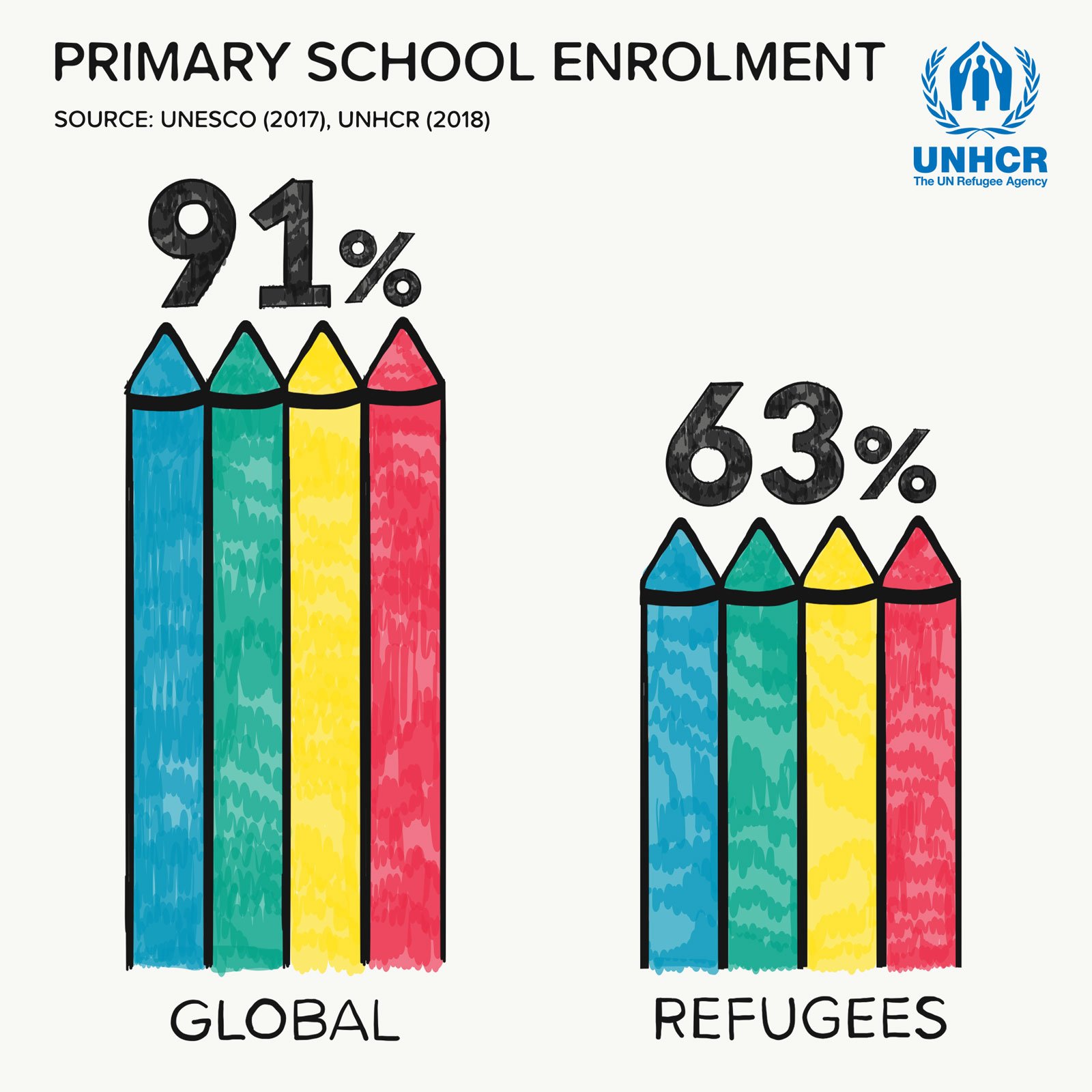

The small gains are thanks to impressive efforts by host states, donors, UNHCR staff and partner organizations to get more refugee children into the classroom. A range of countries have made significant progress, from Uganda, Chad, Kenya and Ethiopia in sub-Saharan Africa to Pakistan, Iran, Turkey and Mexico – giving refugees access to schools, making school timetables more flexible, offering special help to children to catch up on missed schoolwork or to learn new languages, training more teachers, providing more educational materials and helping children adjust to the challenges of life as a refugee.

The rise also reflects a commitment by an increasing number of host governments to include refugee children and youth in their national education systems – the essential, fundamental strategy for boosting enrolment. Providing all learners with a proper curriculum and school certification is the pathway to progressing to secondary and higher education, and onwards to employment. In Rwanda, for instance, thousands of refugee children have been enrolled in primary schools thanks to progressive government policies and targeted funding from donors. In Uganda, 23,000 over-age learners who were previously out of school are now participating in primary education thanks to accelerated education programmes.

Alamuddin, 16, an unaccompanied child refugee from Ethiopia, was able to join an accelerated education literacy class in Yemen thanks to the Educate A Child programme. Three years on, his Arabic skills allowed him to enrol in the 7th grade in a national school. © SDF/MAJED AL-ZOMALY

Turkey, which now hosts 3.7 million refugees, including 1 million school-age children, has implemented a Turkish-language programme – along with new learning materials, subsidized transport, additional teacher training and other measures – to prepare refugee children for the transition from unofficial temporary schools to Turkish ones. Ecuador has passed legislation to make school enrolment much more accessible for Venezuelan refugee children and youth, even in cases where they do not have the required documentation.

These and many similar initiatives led to gains that were further supported by an ambitious partnership between UNHCR and Educate A Child, which implemented education programmes across a dozen countries that resulted in the enrolment of more than 250,000 children in primary school in 2018.

Yet this commitment to giving refugee children and youth the same access to the full range of educational opportunities – from pre-primary right up to higher, as well as technical and vocational education and training, and non-formal education that leads to recognized certification – is not universal. Uncertified parallel systems persist as a temporary response to refugee emergencies, even though they are usually of poor quality, are far less likely to follow a formal curriculum, and result in unrecognized certification. As a consequence, children who have worked with dedication and courage in temporary learning centres finish their studies with no official qualifications and little hope of progressing to a formal secondary education. As long as refugee children are shut out of national systems, the gap in enrolment will remain.

© UNHCR/CLAIRE THOMAS

Morsal, 12, was a refugee in Pakistan and returned to her native Afghanistan in 2016. She is the only girl in her sixth-grade class. Over the years, all the other girls – along with many boys – have dropped out to help with household responsibilities, start working or get married.

Morsal managed to stay in school but has had to battle huge odds, from a lack of infrastructure to cultural pressures. “I love science and English,” she says as the wind blows dust around the 520 students gathered in the field where this makeshift school stands.

The difficulties facing Morsal and her fellow students – including 200 other girls – are representative of the many challenges plaguing the education system in Afghanistan. Children in a village north of Kabul hope a UN-funded school building will encourage parents to allow more of them to stay in education.

Even countries that have made robust efforts to have all children included in education systems can be hindered by shortfalls in resources or undermined by conflicting policies. For instance, over the past two years Greece has set up official kindergartens and increased the number of special reception classes in primary and secondary school to integrate refugee children into state-run schools on the mainland. On the islands, by contrast, where thousands of refugees reside in often overcrowded conditions in five reception centres, little progress has been made in enrolment. Asylum-seekers are expected to stay only temporarily in island facilities but the process of moving them to the mainland can take months, and in the meantime children are unable to access formal education. With the additional issue of the language barrier, some refugees miss out on several years of school.

Evidence suggests that building and broadening the capacity of national education systems benefits local communities and refugees alike. It not only strengthens existing education services for all children and youth but also promotes social cohesion and tolerance of people from different backgrounds. Between 2009 and 2018, for instance, the Refugee Affected and Hosting Areas initiative in Pakistan invested more than US$45 million in over 730 educational projects. Of the nearly 800,000 children who benefitted, 16 per cent were Afghan refugees while the rest were local Pakistanis.

An entire childhood in exile

In 2018, almost four in every five refugees were in protracted situations – up sharply on the previous year[2]. As a result, children who have been forcibly displaced across borders are likely to remain there for much if not all of their childhoods. That means refugee children are very likely to go through an entire school cycle – from age 5 to 18 – in exile, while those who had begun school before being uprooted may well never return to the classrooms with which they were once so familiar. Given that nine refugee situations joined the “protracted” list last year, more and more children face missing out on school if their education is not prioritized.

Education is such a priority for refugees not least because children under 18 comprise about half of the global refugee population. And there are parts of the world where children far outnumber adults, especially in the low- and middle-income countries that host millions of refugees. For example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and Uganda, more than 60 per cent of refugees are under 18. Because 84 per cent of refugees live in developing countries – including 6.7 million in the least developed ones – it is clear that those regions are host to high concentrations of refugee children. Yet these are the very areas that struggle to provide enough schools for their own populations, let alone the sudden influx of tens of thousands of new arrivals.

The importance of pre-primary schooling should not be overlooked, either. Very few refugee children participate in pre-primary programmes even though the benefits are long-established, with plenty of evidence to show how much they help children to develop socially and emotionally as well as to make a better start in primary school. If every refugee child could spend their early years playing in a safe place, happy and cared for, they would reap benefits for a lifetime.

© UNHCR/ARTURO ALMENAR

Claudia* fled El Salvador following a barrage of death threats. She left her son Samuel*, 7, with her mother. Samuel missed more than a year of school as his grandmother tried to protect him from the gangs targeting the family. He was reunited with his mother in Saltillo, Mexico, after a harrowing journey.

In 2017, UNHCR estimated that in Mexico’s southernmost states — where most of the Central American refugees seeking safety from gangs wreaking havoc in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala are concentrated — only 18 percent of refugee children attend school. This is despite legislation that guarantees all children on Mexican soil have the right to enrol in state schools, regardless of their immigration status.

But in Saltillo, it is a different story. For refugees relocated here, UNHCR identifies suitable jobs for adults, assists in enrolling children in school and provides psychosocial support. Refugees also get legal help in acquiring naturalization, which normally happens within two years, and in obtaining their own home, which happens within three. Some 92 per cent of the refugees who moved here have been successful in finding a job. All children are enrolled in school.

*Names have been changed for protection reasons.

Obstacles at every step

By its very nature, displacement disrupts children’s education because of the difficulties and dangers they face in reaching safety, accessing vital basic resources, acquiring new identity documents and helping their families in often vulnerable situations. Compounding this are numerous other obstacles that stop refugee children from resuming school.

First, in the under-resourced regions in which millions of refugees are located, there may not even be a school to attend. Where one exists, it may already be stretched to breaking point – with overflowing classrooms, a lack of teachers, a shortage of basic facilities such as water, sanitation and hygiene, and insufficient teaching and learning materials.

The chaos attending forced displacement also means that many people flee home without the documents – birth certificates and other forms of identification, educational records and exam certificates – that grant them entrance to a local school in a new country. Even when they have those records, a school in another country will not always accept them. Despite Ecuadorian efforts to make school enrolment more accessible, a recent survey found that missing documentation was one of the main reasons why refugee children were not in school in the first year (while the biggest barrier in the second year was lack of funds). And school enrolment is only half the battle. As primary-age refugee children get older, fewer and fewer manage to stay the course.

There has certainly been progress at primary level, but the grim statistics at secondary and higher levels reveal how the barriers to the classroom get bigger and bigger – just as the pressures to quit school increase.

CASE STUDY: LEBANON

Friends from different countries are uniting to give Syrian kids a route off the streets and back into class

By offering basic literacy and numeracy courses, the Borderless Centre in Beirut is part of a nationwide drive to get refugee children out of work and into school.

Fahed, 11, a Syrian refugee, was able to stop working and start learning thanks to the Borderless NGO in Beirut, Lebanon. © UNHCR/DIEGO IBARRA SANCHEZ

In a small classroom overlooking the Mediterranean, young Syrian refugees learn mathematics on portable computers – their first steps towards formal education. A few months ago, most of them were trying to make a living on the streets of the Lebanese capital, Beirut.

One of the pupils, Fahed, was just 10 when he started working at a vegetable store to help his mother make ends meet. He put in 10-hour shifts for just US$3 a day. Originally from Aleppo, he fled to Lebanon with his family in 2015 during the brutal battle for control of Syria’s second city.

“My employer used to beat me,” Fahed recalled. “If I couldn’t carry something, he would beat me and tell me I should.”

Earlier this year, however, Fahed enrolled at a learning centre run by the Borderless NGO in the Ouzai neighbourhood of Beirut, and has since stopped working. “It’s very nice here. I learn, study and laugh with my friends,” he said. Every day from 8am until noon he learns Arabic, English and mathematics.

“What we do is get them here, give them a basic education and try to catch up with their levels of education, and ultimately send them into the formal schools,” explained Lina Attar Ajami, a co-founder of the Borderless Centre, herself originally from Damascus.

Lina set up the centre with a Lebanese friend, Randa Ajami. They share not only the same surname, but also many values. As mothers whose children are now grown up, they know the importance of education for youngsters.

“Education is a lifeline for all of us, but especially the young at the right time,” said Lina.

Located in an underprivileged neighbourhood in the city’s suburbs, the community centre runs basic literacy and numeracy classes for more than 150 Syrian children. The classes are a route into formal education, giving refugee children the basic learning they need to enter government-run catch-up programmes.

“Most of them [have not] been to school before because of their situation,” explained Samah Hamseh, who teaches English here. “They come in order to have the chance to go to school. They want to get out of the conditions they are living in.”

Lebanon hosts more than 935,000 registered Syrian refugees, the highest concentration of refugees in proportion to the national population, which is just over six million people. More than half of Syrian refugee children in the country do not attend formal education, even though the Lebanese authorities have organized special afternoon shifts in state-run schools for Syrian students.

Many children have also missed years of schooling and struggle to meet the minimum educational levels required to enrol.

To address this, the Lebanese Ministry of Education has published a framework for non-formal education that is designed to give children who have been out of the classroom for at least two years – or never been at all – a chance to enter public schools.

This is achieved through accelerated education programmes, aimed at helping children who are out of school to catch up with the curriculum. A minimum level of learning is required to attend accelerated education programmes, which is where community centre programmes offering basic literacy and numeracy classes, such as the Borderless centre in Beirut, have a role to play.

Over the past two years, more than 90 children from the centre have gone on to enrol in public schools.

Even where children are unable to enrol because of a lack of places or funding, the programme still provides important benefits, said Vanan Mandjikian, Assistant Education Officer for UNHCR’s Mount Lebanon field office.

“This programme is essential for the future … because basic literacy is something very important for every child,” she said.

CASE STUDY: GREECE

Majority of refugee children on Greek Islands are out of school

Greek islands are struggling to provide schooling for thousands of asylum-seeking children.

Samir, 11, is a refugee from Afghanistan in the Pyli Reception and Identification Centre on the island of Kos, Greece. He takes Greek lessons at the KEDU non-formal education centre. © UNHCR/SOCRATES BALTAGIANNIS

More than three quarters of the 4,656 school-aged children on the Greek islands who are asylum seekers and live in reception centres do not attend school.

It is a situation UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, wants to improve.

“Every child should have real access to formal education as early as possible. More should be done if they are to avoid falling behind,” said Philippe Leclerc, UNHCR Representative in Greece.

Around 1,800 asylum seekers live in the reception centre on the Greek island of Kos in the southeastern Aegean Sea, and conditions there are difficult, in part because it was set up for a temporary stay and for just 800 people.

Many of the refugees say they are angry about the poor conditions and overcrowding at the centre, which does not even have enough toilets. Accommodation includes makeshift shelters held together with sticks, while some recent arrivals said they did not have mattresses. Several people said overcrowding and lack of facilities meant the centre was not safe. For the children this is a particularly stressful situation.

“The camp is awful,” said Samir, 11, who is concerned about growing frustration among people at the reception centre.

Like most other refugee children, Samir and his friends want to get back into school as soon as possible and make up lost time before the gap becomes too large to bridge.

However, Samir, who arrived on Kos from the Afghan capital Kabul, knows he is one of the lucky ones.

Even though his overall education was disrupted because of the security situation in Afghanistan and he again missed school during his journey overland to Turkey and on to Greece by boat, he is back at school.

He has started to learn Greek by gaining access to KEDU, a non-formal school on Kos that is run by a Greek NGO, the Association for the Social Support of Youth, and supported by UNHCR.

Asylum-seekers are expected to stay only temporarily in island facilities and those who complete procedures or are particularly vulnerable are authorized to move to the mainland. But in reality the process can take many months. Priority is given to competing humanitarian needs. The low population of local children on tiny islands means that often the schools are too small to cope with this sudden new demand.

Around 112 children attend KEDU daily. There are no exams or homework, but the school uses projects and fun to introduce young asylum seekers to Greek. As an informal school, there are no certificates to show the progress.

According to UNHCR, a certified school that is based on the national curriculum should be accessible for all refugee and asylum-seeking children in Greece.

School routine helps restore normality after the trauma many young refugees have endured and starting quickly helps them return to a form of normality. Beyond that, young refugees – just like any other child – need school to achieve their potential.

But unfortunately it is not that easy.

The language barrier makes integration hard. The Greek government provides some afternoon classes to help asylum seekers cope with the transition to a new system and local non-governmental organizations have stepped in with support for homework.

UNHCR says more is needed. The government has tried to include all asylum-seeker and refugee children in formal education, but the islands face particular challenges. Even those asylum-seekers on the Greek islands who are eligible for the move to the mainland are often unable to leave because there is not enough accommodation ready for them, while new arrivals outpace the rate of transfers, exacerbating the overcrowding issue.

“Most refugee children on the Greek mainland are enrolled in formal education as the school year begins. Greece has made important progress in granting access to kindergartens, and primary and secondary schools. Now the Government must expand and consolidate its efforts, with the continued support and funds from the EU, so that all refugee children can enter a classroom,” Leclerc said.