CHAPTER 3:

TERTIARY EDUCATION

OUT OF REACH

Weam (left), 19, and Diala (right), 18, Syrian refugees, arrived in Lebanon in 2015. Weam is completing her first year in computer science at Lebanese University and Diala is a first-year biology student, both thanks to a DAFI scholarship. © UNHCR/ANTOINE TARDY

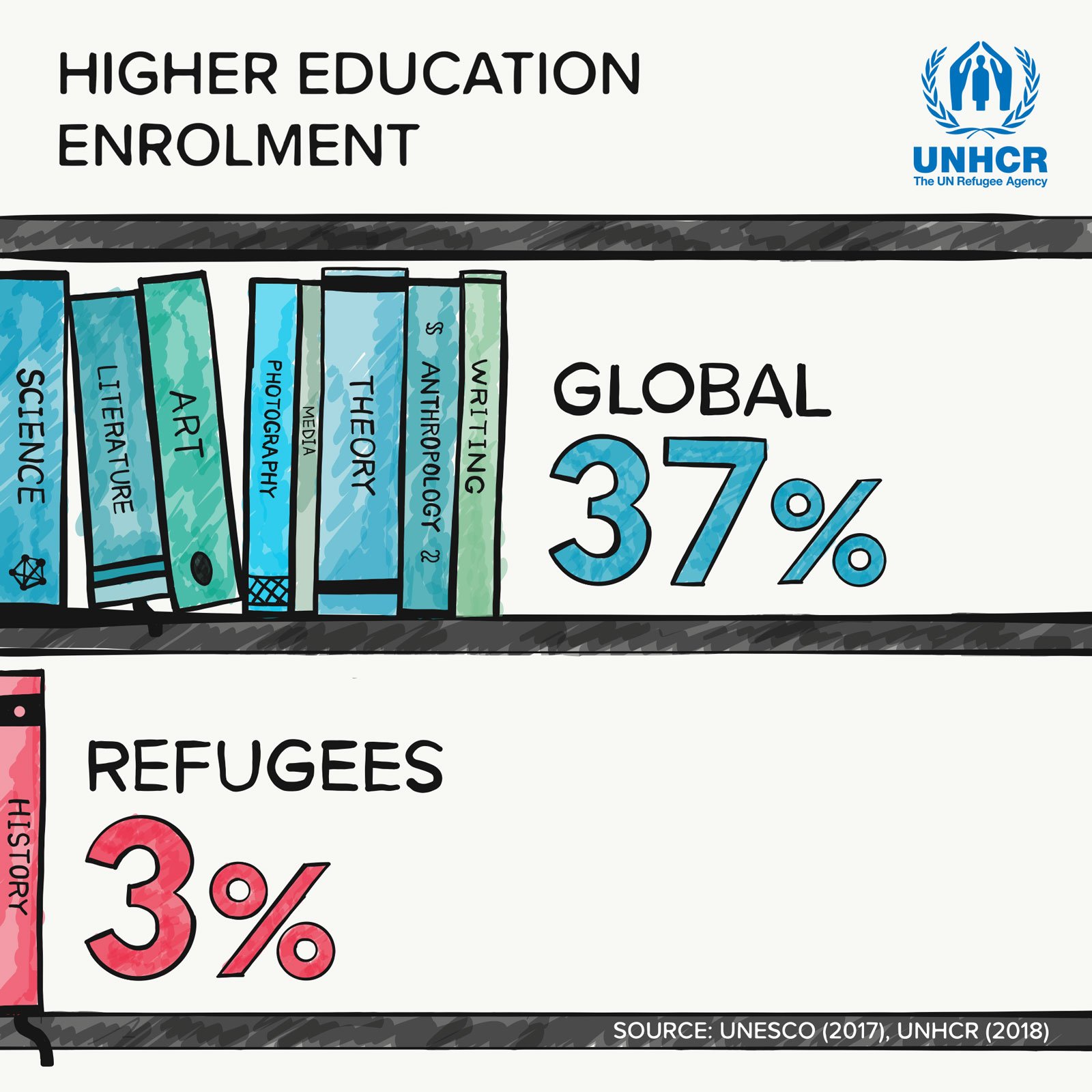

It should be cause for celebration: in 2018 there was a sharp increase in the number of refugees going on to higher education. In reality, the rise in enrolment from 1 to 3 per cent, while certainly a move in the right direction, pales in comparison to the global figure of 37 per cent. The gap in secondary education opportunities for refugees compared to non-refugees is so wide that the knock-on effect on higher education continues to be dramatic.

Over the past three years, the data has pointed to an apparently intractable problem: only 1 in 100 refugees of the relevant age was enrolled in some form of post-secondary education, a figure that seemed impossible to budge – until now. The small but significant shift to 3 per cent enrolment in 2018 means that there are now a total of 87,833 higher education refugee students. With secondary education provision largely static, this improvement is largely attributable to a greater acceptance on the part of states, higher education institutions and their partner organizations of the importance of higher education in nurturing leaders among the refugee population. Connected higher education, where digital programmes are combined with teaching and mentoring, continues to extend opportunities for those who cannot access a university. And data collection on refugee enrolment is improving as the issue rises up the agenda.

All this has led to increased investment in, and greater numbers of, scholarships, grants and innovative connected learning programmes. As such opportunities expand, education providers are also fostering a more welcoming environment for refugee students.

Even so, 3 per cent compares poorly to the global statistic for the world’s youth. And it is still a long way off UNHCR’s target of seeing 15 per cent of the eligible refugee population in higher education by 2030[1].

Yet among those who have managed to navigate the many daunting obstacles and have completed their secondary education, demand for degrees, connected education and vocational programmes remains high. For example, the DAFI programme[2], funded by the German government and other partners, is able to award scholarships to only 1 in 5 applicants. Without question, the appetite for higher education among refugees is strong and remains largely unmet.

For refugee girls and women, the prospect of attaining higher education is even slimmer. Forty-one per cent of refugees who enrol in DAFI scholarship programmes are female – by contrast, according to UNESCO data there were more female than male graduates from higher education in three-quarters of the world’s countries. Some progress can be seen for Syrian refugee students, where enrolment stands at 52 per cent for girls – but much more needs to be done to help them battle the social and cultural conventions that prevent them from reaching their potential.

© UNHCR/GORDON WELTERS

Just a year after he arrived in Berlin, Germany, in 2015, Ehab Badwi, 26, a Syrian refugee, set up the Syrian Youth Assembly, an online network that gives would-be students access to higher education. Three years later, around 40,000 young Syrians belong to the network’s Facebook group and 12,000 people have completed online courses.

“We are trying to build peace in Syria in a non-political way. We speak about how education and development can be key to that,” he says.

Obstacles at every step

Certificates, languages and cost comprise some of the biggest barriers to higher education for those who make it through secondary school. During flight, many refugees lose or damage the documents that prove their qualifications or prior learning, while the countries where they seek refuge may not formally recognize certificates issued by their homeland. Secondly, the academic demands of higher education call for advanced language skills. It can take months or even years to master a new language to this level. Thirdly, the high cost of tertiary education can deter or exclude many students – especially if, as is the case in some countries, refugees are required to pay the higher international student rates. When weighing such costs against competing (and often more pressing) obligations to work, it is easy to see why such a small number of refugees make it to higher education.

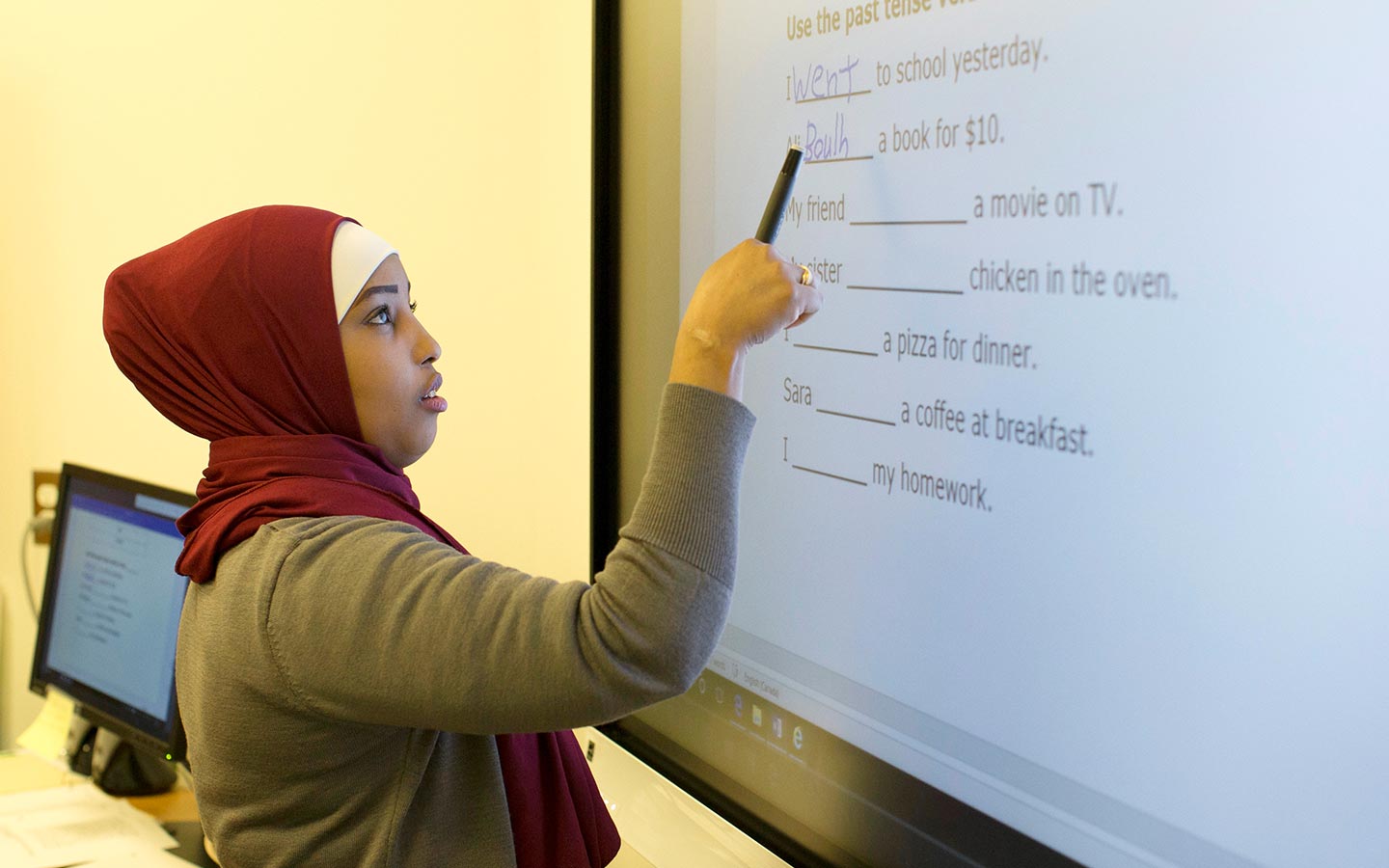

Iqra Ali Gaal, 25, a Somali refugee, attends English classes as part of the language instruction for newcomers to Canada programme at College Boreal in Hamilton, Canada. © UNHCR/CHRIS YOUNG

Yet access to higher education is life-changing. It opens new horizons and creates opportunities that seemed to have disappeared in the chaos of displacement. It is a powerful agent for sustainable development when linked to the right to work, offering as it does a route to socio-economic inclusion in host countries and a reduced dependency on humanitarian aid – in short, turning refugees from financial and social dependents into self-reliant contributors to society.

As of 2018, however, around 50 per cent of refugee-hosting countries did not allow refugees to work[3], a self-defeating policy which means that refugees who have overcome all odds to access and complete higher education find themselves back in a state of limbo, unable to use their skills and fulfil their potential.

To break down this wall, the DAFI programme is expanding to a scheme called DAFI+, which aims to engage national authorities, business and labour organizations in helping refugees overcome this barrier. DAFI+ is piloting in Pakistan with the support of the German Corporation for International Cooperation, GIZ, and in 2018 placed dozens of refugee graduates into work and internships. The ambition is to inspire similar projects all over the world.

Farzana, 21, an Afghan refugee, was granted a DAFI scholarship in 2016 that enabled her to complete her bachelor’s degree in pharmaceutical studies in Islamabad, Pakistan. She graduated in 2018 with excellent grades, finishing second in her final exams. Thanks to DAFI+, Farzana is now able to put her skills in practice in an on-the-job training as a clinical pharmacist at Islamabad Medicure Hospital. © UNHCR/ASIF SHAHZAD

Closing the gap

To bring the 2030 higher education target within reach, first and foremost refugees must have far greater access to a quality secondary education. After that, as a minimum those who complete secondary school must be allowed to apply for, and enrol in, higher education under the same conditions as nationals.

Furthermore, refugees need additional support to meet the daunting cost of education. Universities and other institutions that offer scholarships, bursaries and support services for students from marginalized backgrounds should extend them to refugees. Scholarships for refugees in their host country and abroad should consider the full cost of tuition and living – including the potential economic impact on the student’s family when they are studying full time and unavailable to work.

The private sector has a role to play, too, by becoming key investors in higher education for refugees. In 2018, only 10 per cent of the DAFI budget was funded by the private sector[4]. The private sector could go further by helping refugee graduates find suitable employment opportunities – offering them internships, mentoring programmes, career guidance and, where possible, jobs.

Refugee students from the Democratic Republic of the Congo participate in Kepler’s Iteme Programme in Huye, Rwanda, which helps refugees and host community students improve their English and math which will increase their chances of being admitted in higher education programmes. © JULIA CUMES

The social and economic barriers that hold girls back at every stage are also a reality at the level of higher education, and demand extra efforts if they are to be overcome. In Rwanda, for example, Kepler’s Iteme (“Bridge” in Kinyarwanda) secondary school girls make the transition to further education by giving them extra training in English, mathematics, and information and computer studies to improve their chances of conquering the admissions process, while also assisting them when they apply to tertiary education opportunities in Rwanda. Iteme served around 140 students in 2018, 40 of whom were Rwandans from vulnerable backgrounds. By the end of the year, 40 per cent of the student cohort had successfully enrolled in further education.

Higher education is not a luxury – it is an essential investment It gives young refugees the perspectives, maturity and experiences they need to become peace builders, policy makers, teachers and role models. It gives women the platform to participate in society on an equal footing with men. And it forms the people who contribute to their host communities, act as the voice of their fellow refugees and, one day, rebuild their home countries.

CASE STUDY: KENYA

Technology connects Somali refugee with university in Canada

Despite being thousands of kilometres away, a group of refugees in Kenya’s Dadaab refugee camp are studying at Canada’s York University. From seven master’s students, the programme is now expanding to 60 learners.

Abdikadir Bare Abikar, 29, a Somali refugee, is pursuing a master’s degree in education from Canada’s York University. He is studying online from Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, where he lives with his wife and three daughters. © UNHCR/ANTHONY KARUMBA

Abdikadir Bare Abikar, 29, is on the verge of completing his Master’s of Education from York University in Canada.

That fact may be not particularly remarkable. What is remarkable is that he is doing it 12,000 kilometers away from Toronto. Since 2013, Abdikadir has been studying online from Dadaab’s remote Ifo refugee camp in Kenya. He is one of only seven refugee students enrolled in a master’s degree in a camp of more than 200,000 people.

Every day, Abdikadir walks for almost two hours on the sandy, rocky roads of Dadaab to the computer lab, where he connects to the online learning platform that allows him to speak to his classmates and professors.

“Education changes a person. It has transformed me,” says Abdikadir, who is now a teaching assistant for the new cohort of students at the camp. He has recently co-authored an article in the Forced Migration Review, a journal edited by the Refugee Studies Centre at Oxford University, and is busy writing a chapter for a book to explain how Dadaab has benefited from technology.

His professors at York University could not be more proud. Don Dippo, Professor of Education at York, explains:

“The refugees that have been trained are now in a position to replace the faculty that taught them years ago.” He adds with a smile: “I long for the day when Abdikadir will be my professor and I will be his teaching assistant.”

Abdikadir knows he is defying the odds. Globally, only 3 percent of refugees are able to access university. The road that has taken him there has been a harrowing one.

By the age of 10, he was an orphan. His father passed away from illness and his mother was killed by members of a militia in Somalia. Fearing for their safety, Abdikadir’s older brother Adam, who was only 15 at the time, fled with him to Kenya. They found refuge in Dadaab. That was 20 years ago.

As soon as he arrived at the camp, Abdikadir enrolled in primary school. With his brother’s help, he excelled in his studies. But even for those who make it all the way through secondary school – an achievement in itself – accessing higher education from somewhere as remote as Dadaab isn’t easy.

Technology provided a solution. Studying online, Abdikadir obtained a teaching diploma from Kenya’s Kenyatta University, one of 23 universities that are part of the Connected Learning in Crisis Consortium, co-chaired by UNHCR. Today more than 12,000 students worldwide are on courses supported by the Consortium.

Abdikadir didn’t stop there. Determined to keep going with his education, he applied for a Bachelor of Arts programme at York University, another member of the Connected Learning in Crisis Consortium, and was accepted. He is now also doing his master’s there.

Abdikadir stresses that studying online does not leave him disconnected from the university campus experience. He follows most of his courses face-to-face with his professors and constantly interacts with his fellow York students. “We learn from each other and exchange ideas on the learning platforms. The PhD students also kindly help proofread my assignments,” he explains.

He has even been elected as one of the representatives of York’s Graduate Students Association.

“I am the information technology coordinator. All the way from Dadaab, I help improve the social media protocols of York University.”

Abdikadir has high hopes for his future and that of his three daughters, aged three and a half, four and five. “As soon as they reach four years old, I will take them to school.

He wants to use his education to make a difference. “One day, I will be a changemaker and go back to my homeland, Somalia. I want to apply new ideas and help bring education to communities outside cities,” he says.

“Without education, a person’s eyes are always closed.”

CASE STUDY: COLOMBIA

Daniela’s dreams of becoming a doctor on hold as she struggles to provide for family

While many Venezuelan refugees and migrants in Colombia have enrolled in school, without the right papers, they cannot be issued diplomas and may not sit the national college entrance exam, putting their future at risk.

Daniela Puente, 22, fled Venezuela in 2018 when she was just a few courses away from graduating from medical school. She currently works as a waitress in Bogotá, Colombia, hoping to make enough money to one day go back to university. © UNHCR/HELENE CAUXS

All her life Daniela Puente dreamed of becoming a doctor.

Four years into medical school, it was almost within her grasp. Then came Venezuela’s crisis.

Her life was thrown into turmoil and like 4.2 million of her compatriots she had to leave. Uncertainty now clouds her future.

Her dreams began to fade the penultimate year of medical school in Merida, Daniel’s hometown in western Venezuela.

Suddenly the university cafeteria stopped serving its usual copious breakfast of eggs, arepas, pancakes, and fruit. Instead, students got a glass of warm milk.

It was a symbol of the crisis that had turned her university into a shadow of its former self, deserted by faculty and students alike, and reduced her middle-class family to penury. Meals were becoming so scarce her younger brother was wasting away. Daniela knew she had no choice but to flee.

“My family is the most precious thing in my life, so I knew I had to walk away from all my dreams to make sure they survived,” said Daniela, now 22.

That also meant dropping out of medical school even though she had worked so hard to get there, juggling a demanding class load with a part-time job as a waitress. If she managed to get to Colombia, she reasoned, perhaps she could register at a Colombian university to finish the few classes she still needed to get her degree.

In February 2018, Daniela slipped across the border, using nearly all her savings to buy a one-way bus ticket to the Colombian capital, Bogotá. She arrived with just 10,000 Colombian pesos, about US$3, to her name.

Her plans hit problems immediately. Public universities required a student visa and notarized copies of her high-school diploma and her medical school transcripts – official documents that are all but impossible to obtain in Venezuela. The private universities were more flexible on documentation but the fees put them out of reach.

Daniela’s problems are faced by many of the four million Venezuelans estimated to have left their country amid the ongoing crisis, which has taken a heavy toll on economic stability, public security and basic healthcare.

A recent UNHCR report, based on interviews with nearly 8,000 Venezuelans, revealed that less than half of the children were attending school. The report cited the reasons as being “lack of documentation to enroll, limited space in (host country) public schools and lack of financial resources to cover the fees.”

In Colombia, which hosts the highest number of Venezuelan refugees and migrants, the authorities have made some progress towards removing these barriers. Some primary and secondary schools are enrolling Venezuelan children regardless of their documents or legal status. The Bogotá region recently reported an increase of more than 600 per cent in the number of Venezuelans enrolled in its public primary and secondary schools – from around 3,800 in August 2018 to 23,000 the following May.

But this decision does not solve everything. Without the right papers, students cannot be issued diplomas and may not sit the national college entrance exam, for example.

That’s the issue facing Andrea González, 17, who fled Venezuela in late 2017 with her family in the first term of her final year of high school. After settling in Cúcuta, a Colombian city near the border and a major point of entry for Venezuelans seeking safety, Andrea and her mother started lobbying the director of the nearby public school to allow her to attend classes. Like Daniela, she lacked proper documents.

Eventually the director relented, although she was then placed in the ninth grade, two years behind where she should have been.

Undaunted, Andrea said she saw this not as a demotion but as “a chance to learn more and hone my skills”. Now in tenth grade, she’s top of her class and has set her eyes on university.

But unless the law changes in time, Andrea’s legal status in Colombia will prevent her from sitting the entrance exam that is a prerequisite to get into any Colombian university. She is staying optimistic, saying: “I think things will change by the time I get there and that I’ll be given a chance to make the most out of my life by going to college.”

Daniela is similarly hopeful. At present, she is a waitress in a Bogotá restaurant, earning slightly more than the monthly minimum wage of around US$250 – the lion’s share of which she sends home to her family.

“There are so many of us young people who have been forced to abandon our dreams,” she says. “But I know that one day, I’m going to finally become a doctor. I don’t know how, and I don’t know when. But I know it’s going to happen.”