Families settle in Afghan's Baghlan province after years on the road

Families settle in Afghan's Baghlan province after years on the road

Building a new home in Darkhat.

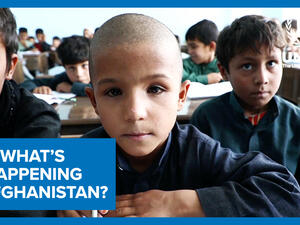

DARKHAT, Afghanistan, October 9 (UNHCR) - The Afghans have a proverb that says: "There is always a path to the top of the highest mountain." It has proved prophetic for a small group of internally displaced families carving out a future for themselves and their children on the fertile plains of Baghlan province.

"We have been living like nomads for 20 years," says elder, Shah Wali, speaking on behalf of 140 families now scattered across a cluster of eight neighbouring villages in Darkhat, a stone's throw from the provincial capital, Pul-i-Khumri. They're still afraid that they will be killed by those who took over their lands if they attempt to return home.

Originally from nearby Sari-Pul province to the west, the families found some measure of peace and stability when they were welcomed by locals to Darkhat three years ago and were allowed to stay after roaming around the north.

Today, young girls in brightly coloured scarves play hide-and-seek behind partially completed shelters provided by UNHCR. Their mothers, meanwhile, bake bread and send their older children to fetch water from a well across the valley, in another returnee settlement.

The air is crisp and the silence almost complete, occasionally broken by the cries of a baby or a donkey. But things weren't always so peaceful and the villagers have faced struggle after struggle.

When they first arrived, the families applied for plots in the nearby Khoja Alwan settlement, set up by the government to provide land to uprooted and landless returnees and internally displaced persons. But a mix of administrative complications and corruption at local government level prevented them from securing land.

"We felt angry and upset. So we decided to come together and buy the land," says Shah Wali. "We didn't have the money outright so we paid what we could and the landowner has given us a credit line for the rest."

Today, 24 families have started to build their homes with the assistance of UNHCR on six jeribs of land, the equivalent of 12,000 square metres. A third of the land has now been paid for. Agreement on how the rest of the money will be paid has also been reached. The initiative is raising hopes for other communities who are landless and who are trying to find land space to build their homes.

"We need to pay attention to what's happened here," says Alex Mundt, head of the UNHCR sub-office in Kunduz. "This is an example of a community that has found a durable solution almost entirely on its own and against all odds."

The issue of landlessness, alongside homelessness and security, is one of the major obstacles facing returnees. Many of them have no choice but to occupy land from which they will be later evicted and on which they cannot rebuild their lives in a durable manner. But despite many difficulties, solutions are being found through dialogue, community efforts and resilience.

"Throughout the country we are seeing returnees use their own initiative to try and solve the most urgent problems, such as homelessness, land ownership and a lack of jobs, water and basic services," notes the head of the UNHCR mission in Afghanistan, Salvatore Lombardo.

"But like all the other problems facing returnees, such initiatives take time, patience and effort. There is a need for a continued and consistent commitment to ensure that such problems can be dealt with on a durable and long-term basis."

For the community in Darkhat, it's a matter of one step at a time. Many of the families are putting the final touches to their homes. While they have now secured their own land and have been able to build their homes with the help of the UNHCR shelter programme, there is still much to do.

UNHCR has also been assisting the community in Darkhat with homes and shelters. Last year, many of the families spent the winter in holes dug in the ground and covered with plastic sheeting.

Today, they still don't have any access to drinking water and schools may be some 25 kilometres away. Job opportunities also remain a problem and the cost of transport to the nearest town is equal to a day's wage.

But for the time being, even if there is still some distance to travel, villagers hope they aren't just settling into new houses. As the last mud bricks are plastered over, they hope they have now reached the end of the path and can finally rebuild a community in a land they can call home.

By Maryann Maguire in Baghlan, Afghanistan