Feature: Barakwena refugees forage and forge ahead in Botswana camp

Feature: Barakwena refugees forage and forge ahead in Botswana camp

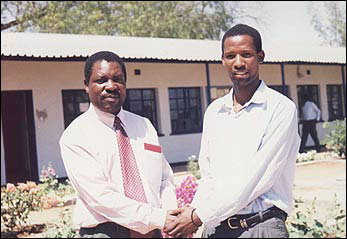

Warm welcome home for Namibian refugee William Mahingi (right) by the acting paramount chief of the Barakwena, Thadeus Chedau.

GABORONE, Botswana (UNHCR) - Jamaica Mahundu comes from a long line of hunter-gatherers, but unlike the older generation, the only things this young Namibian refugee is keen on gathering are skills and knowledge to improve the lives of his people back home.

Reflecting the generation gap, his uncle William Mahingi scoffs: "I know that hunting and gathering is considered old-fashioned. Our children now go to school but what is it worth? We remain hungry with the formal education they have. At least I am able to put food on the table!"

Both men have lived in Botswana's Dukwi camp since 1998, when they fled instability in the Caprivi region of Namibia. After four years in exile, they - along with 2,300 other Namibians at Dukwi - were recently given the option to return home under a tripartite repatriation agreement between the governments of Botswana, Namibia and the UN refugee agency.

"I am so happy!" exclaims Mahingi, turning to gauge his nephew's reaction. Mahundu looks away, more circumspect about his uncle's obvious joy.

The old man is disappointed he cannot persuade his nephew to return home to some semblance of their old way of life. However, Mahingi himself does not know what lies ahead. He has no idea whether his livestock is still alive, whether they have been stolen, or whether his house still stands. All he knows is it is time to return to a more familiar life, albeit now somewhat confined to a more sedentary existence.

Like many of the residents at Dukwi camp, Mahingi and Mahundu are from the semi-nomadic Barakwena ethnic group, also known as the San or the more derogatory Bushmen.

"They are still very traditional and conservative and their survival relates quite significantly to the environment, which they require uninterrupted access to," notes Cosmas Chanda, who heads UNHCR's liaison office in Botswana.

"They are to a certain extent still hunters and gatherers on a small scale," adds Lethlogile Lucas, Public Affairs Officer with the Botswana Christian Council. "Given the restrictions placed on how far they can hunt and gather, they've been forced over time to change their lifestyle to a degree and this hasn't been easy."

"Change for my people has been inevitable," concedes Mahundu, translating for his uncle. "My uncle still forages as much as he can, but the areas he roamed and hunted in as a young person are now private and government-run game parks. If he's found without permission in these areas, he can easily be arrested for trespassing without even realising it."

Though respectful of his roots and his people's lifestyle, Mahundu knows that he is not cut out for hunting and gathering. Neither is he interested in the compromise that the Barakwena have been forced to accept - coaxing a living from their hostile habitat as small-scale subsistence farmers.

Mahundu, who has always dreamt of becoming a teacher, believes that education is key to the Barakwena's future. To pursue his dream, he decided not to follow his uncle back to Caprivi in October.

Francis Mambeleko Kuphulo, a Form 3 student at the Educational Resource Centre, a secondary school at Dukwi camp, also bade his mother and siblings farewell when they returned to Namibia. He chose to stay at Dukwi to complete his studies till Form 5, after which he hopes to pursue tertiary education in Botswana. He says with determination, "Then, and only then, can I return to my people. I have to make it!"

The one who stayed behind - Barakwena student Francis Mambeleko Kupulo (right) with his school principal at Dukwi camp, Frederic Musonda.

Primary and secondary education is free at Dukwi. Refugees who wish to go on to university in Botswana or the region pay the same fees as local students under a UNHCR-negotiated waiver of the foreign student levy.

"We have 11 refugee students enrolled in the University of South Africa, two in Namibia and three in Botswana," says UNHCR Botswana's Chanda. "Any person who passes through university is more likely to find a job and leave Dukwi and support his family. We are confident that this is one way of finding a better durable solution for refugees."

Frederic Musonda, Principal of the Educational Resource Centre, adds, "From what I have seen, the Barakwena students are highly intelligent. But as they grow older, other things occupy their minds, like getting married. I suspect that because of these distractions, pressure from their married or pregnant peers and even from their parents, their interest in school diminishes and eventually they leave. I believe it is a cultural thing."

"It is true," confirms Kuphulo. "Girls and boys marry young and drop out of school. Unfortunately, we do not have positive role models in our community who can talk about the benefits of completing our education. There are no formally educated Barakwena of note, at least not that I'm aware of, and our parents cannot help either because they only want their old life back."

Kuphulo adds, "As a young person, I have no choice but to encourage and push myself. Fortunately I have good friends among the other refugee students who help me stay focused and strong. If I do well, I intend to be one of the people to turn things around in my community. Life is different today and young Barakwena have no choice but to be prepared for it, otherwise they'll always be at a disadvantage."

Unfortunately, the recent repatriation meant that some of the refugees had to compromise their studies. Principal Musonda notes that about 20 students have left since August. "I'm made to understand that the schools they will attend back in Caprivi lack serviceable facilities, so I was requested to provide them what the Resource Centre could spare. We gave them textbooks, exercise books, stationery and school uniforms. We also urged them to write to us with whatever problems they had and hopefully we will be able to assist wherever possible."

But even for those who remain at Dukwi, success is not guaranteed. Mahundu has failed to secure financial assistance for college, especially given the UN refugee agency's limited budget and funding shortfall. But confident that qualified teachers are few and far between back home, Mahundu says he will reapply for financial assistance to study in 2003. However, if he is unable to realise this dream, he will settle for being a shop assistant or cattle herder, which seems to be his uncle's preference.

For the time being, or at least until the next phase of the repatriation exercise in March 2003, Mahundu will continue to take advantage of the protection and assistance offered by the government of Botswana and UNHCR as he ponders the direction of his future.

By Pumla Rulashe

UNHCR South Africa