Refugees lobby for identity in South Africa

Refugees lobby for identity in South Africa

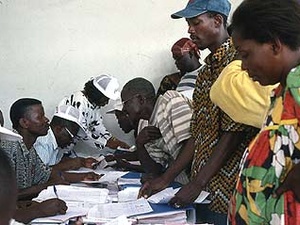

An Angolan refugee (right) explaining the validity of his identity document to a security official in Pretoria.

PRETORIA, South Africa (UNHCR) - When Omari Shabani became the first person to receive a refugee identity document (ID) in South Africa four years ago, he said he was "overwhelmed" and hoped it would make his family's life "easier and better".

Today, the Congolese refugee is a counsellor with a youth HIV/AIDS prevention programme at the Planned Parenthood Association of South Africa. With an honours degree in psychology, he is pursuing a Masters Degree in Public Health at the Medical University of South Africa.

So has the identity document changed his life?

"After I got it, it made things a bit easier," says Shabani after some hesitation. When prodded, he admits that most people from police officers to shopkeepers and bank tellers do not seem to recognise his refugee ID. "I don't know if it is because of a lack of information, or if they are doing it purposefully because of xenophobia, but whenever they ask for your identity number, and you produce the refugee ID, they act like they have never seen before."

The South African government first introduced these IDs when the Refugees Act 1998 - drafted with help from UNHCR and non-governmental organisations - came into effect in April 2000. This gave refugees access to services that were not readily available to them previously, and gave them the right to apply for IDs and permanent resident status.

"Our society and its legal structure are very institutionalised and therefore it is extremely important for refugees to have IDs," explains Fritz Gaerdes, a legal counsellor with Lawyers for Human Rights, one of UNHCR's implementing partners in South Africa. "Without an identity document here, you cannot do anything, you're nobody."

However, problems have arisen from the fact that refugee IDs are maroon in colour, while South African IDs are green.

"Most people would not recognise a maroon-coloured refugee ID as valid, unless they look up the Refugees Act 1998 and the description of the document. At face value, it will not be recognised as a bona fide identity document in South Africa, and therein lies the problem," says Gaerdes.

He adds, "Legally living in a country with serious levels of xenophobia, we don't necessarily want refugees to stand out as different and easily identifiable. That way, their rights are easily violated. We want them to blend in and integrate. That should be part of the government's strategy. I know it is part of UNHCR's and this is one of the tools through which local integration must be facilitated."

UNHCR's Assistant Representative for Protection Abel Mbilinyi says that the agency has been urging the South African government to change the format and even the nature of the document, or to make the refugee ID the same as a South African one.

"In a society where everyone is identified by 13 digits [on the ID card], the ID is critical in promoting integration for refugees," says Mbilinyi. "In some cases we have been arguing for public relief such as social grants for refugees. The government has made it very clear that it will consider, in the long run, such assistance to refugees, but an authentic and acceptable ID is primary in identifying somebody who qualifies for such assistance."

Congolese refugee Shabani says he is able to succeed in accessing services nearly all of the time, because he is more persistent than most. He makes it his business to exercise his rights, even if it means spending several hours in lengthy discussions on his status in the country. Ultimately, he may be able to persuade service providers to do business with him.

He says, "But what of the many refugees who cannot speak English or any of South Africa's 10 other languages? Besides, who has the time or the patience to always explain that their ID is valid? You feel defeated before you've begun. The situation is still very difficult and complicated."

Despite these difficulties, Lawyers for Human Rights, the Department of Home Affairs and UNHCR all agree that to a certain extent, some refugees have benefited from the IDs. Richard Sikhakane, Assistant Director of Refugee Affairs at South Africa's Ministry of Home Affairs, says that it has made it easier for refugees to access employment and to travel outside South Africa, whenever they need to.

"According to my knowledge," notes Sikhakane, "the refugee identity document was introduced to quite a number of sectors, including business, banking institutions, the transport sector and education, to name a few. I think the problem lies with managers not informing relevant staff so that in the end, front line staff who engage with the public remain unaware of the refugee ID."

Asked if organisations or businesses like a bank can be forced to provide services to refugees, he states, "If refugees experience problems with certain institutions, then we at Home Affairs would be willing to give clarity to those institutions on the legislation affecting this issue, so that they accept the refugee ID, on verification on its validity. Institutions are bound to offer refugees services, without discrimination."

He adds that any refugee facing problems should consult the Refugee Reception Office.

"Theoretically, yes that is what should happen," agrees Gaerdes. "However, we have on numerous occasions taken this matter up with Home Affairs but our interaction with them has not been as positive as we would have liked."

Sikhakane is quick to add that South Africa is still relatively new to the refugee situation: "Ten years into its democracy and almost three years since the Refugees Act 1998 came into effect, there are bound to be serious difficulties with institutions being suspicious and wary with the unfamiliar. Many institutions don't realise, for example, that the refugee identity document has more security features than even the green ID. It is not an easy document to forge."

Recently, the South African Director General of Home Affairs informed UNHCR that the government has in principle agreed to issue the green ID to refugees, hopefully during the course of this year. In the longer term, refugees will receive a "smart card".

"We are in the computer age where everything works with the swipe of a card," says Sikhakane, adding that the fingerprint-based system will first be introduced to refugees, then to South African citizens.

"Refugees will be initiated into this as a pilot, to see how successful this system will be and whether it needs any modification. South Africa will also change from the green book to the smart card, which will be the same ID document for everyone legally resident in the country, with some distinguishing features. This will ultimately take place in the near future."

With this news, Shabani and many refugees around South Africa are optimistic. South Africa has become their home away from home, but without valid and widely recognised identity documents, they will remain feared, fearful and faceless.

By Pumla Rulashe

UNHCR South Africa