In Kutupalong, small acts can keep hope alive

In Kutupalong, small acts can keep hope alive

Less than ten years ago, hardly anyone knew what the term “Rohingya” meant. Today, it is tied to one of the clearest crises of forced displacement in our time.

Rohingya refugees play soccer at a refugee camp in Cox's Bazar.

The Rohingya are often considered “one of the world’s most persecuted minorities.” An ethnic group native to what is now known as Myanmar, they were stripped of their citizenship and over time forced to flee their homes in the face of horrific violence and targeted persecution. The most recent exodus came in August 2017. According to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, more than 750,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh—many forced to leave at a moment’s notice as their villages came under attack, carrying only what they could. Today, more than 1 million Rohingya refugees live in Bangladesh.

To this day I still think about what “only they could carry” actually looks like. A child on the hip. A bag with a change of clothes. An elderly mother too weak to walk. That is how they arrived in Bangladesh; exhausted, traumatized, and carrying the entirety of their lives in their arms.

In Cox’s Bazar, what was once forest has become a vast settlement: Kutupalong, now the largest refugee camp on earth. The population is bigger than that of Boston, Las Vegas, or even Detroit. It has the density and rhythm of a city, but it is built from bamboo and tarpaulin. Most Rohingya cannot safely return to Myanmar, and in Bangladesh their lives are constrained by overcrowding and limited opportunities. And nowhere is that limbo more visible, or more heartbreaking, than among the children.

As humanitarians, we carry a different kind of weight in places like Kutupalong. We can leave. Refugees cannot. We can get on a plane and return to running water that doesn’t make our children sick, to a life where the biggest worry is homework and bedtime. That contrast stays with you. And it also sharpens what our work demands of us: showing up, day after day, even when it means making sacrifices of our own.

One year while working in the camp, I was able to return home for Christmas. I had been away from my family for some time, like so many of my humanitarian colleagues who miss birthdays, graduations, and everyday routines so they can help build safety and stability for families who have lost everything. But even at home, Kutupalong stayed with me, and before long with my children too.

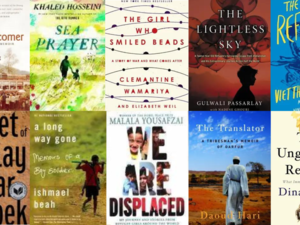

My children, then seven and five, were so happy to have me back for Christmas that they didn't want me to leave again. I then showed my children videos from Kutupalong, and after watching, my daughter told me, reluctantly, that I could go back—but only if I brought toys for all the Rohingya children. She offered to part with a doll, then paused and realized that giving one doll to one child would only create more sadness for everyone else. The next day she ran in with an answer: soccer balls. “If you bring soccer balls,” she said, “everyone can play together.”

So we bought as many soccer balls as we could find, deflating them to fit into a suitcase. Back in Kutupalong, I pumped them up one by one and handed them out to schools and small groups of children. I have rarely seen joy like that—pure, immediate astonishment at something so ordinary to so many of us: a real soccer ball, full of air.

It didn’t change the scale of the crisis Rohingya families face or resolve the displacement that forced so many to flee. But it did underline something the world too often misses: in a place as unforgiving as Kutupalong, no act is too small to matter, and something as simple as a soccer ball can create enduring joy, connection, and hope.

That is the lesson I carry with me. You can do very much with very little, a ball for a child, bread for a mother, sleeping bags for a family. In each case, you are doing more than meeting a need. You are offering dignity, and a reason to keep going, whether it’s Christmas or not.