In Utah, refugee sisters explore the physics of the universe

In Utah, refugee sisters explore the physics of the universe

Sisters Lina and Neriman explore cosmic rays through their original research, redefining what it means to belong in science as young refugee women.

In many ways, Lina and Neriman's refugee journey from Iraq to Utah parallels that of a cosmic ray: covering great distances, breaking barriers, and carrying light into new places.

The bright and charismatic sisters arrived in Utah as refugees with their family more than a decade ago. While memories of their life in war-torn Iraq have blurred over time, they remember vividly the challenges of adjusting to a new country. But, over the years, Utah has become more than just a place of refuge: “We made Utah our home,” Lina says with a smile. “It’s the best thing ever.”

As they grew more comfortable in their new environment, the sisters began seeking opportunities to learn and explore.

Their curiosity about the world gained purpose when they joined an after-school and summer program at the University of Utah, founded by professor Tino Nyawelo. Originally from South Sudan, he recognized the potential of refugee students and set out to create pathways for them to thrive. “At first, it was an after-school program to help refugee students with homework and schoolwork, and we later expanded it to guide them in transitioning to university after high school.” Today, Nyawelo’s program, now called REFUGES (Refugees Exploring the Foundations of Undergraduate Education in Science), provides hands-on science education, mentorship, and a space where students, including refugees, can feel like they belong.

For refugee students, programs like REFUGES can be life changing. There are 12.4 million school-aged refugee children worldwide, and nearly half are out of school, according to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. Those who do have access to formal education often encounter obstacles such as language barriers and a lack of resources, making it even more challenging to pursue fields like science, technology, engineering, and math.

In the face of these challenges, Lina and Neriman’s experience demonstrates that access to opportunities can spark curiosity, open doors, and alter life trajectories.

It was within that supportive setting that the sisters first encountered a topic that would leave a lasting impression: cosmic rays. These high-energy particles from outer space collide with Earth’s atmosphere, breaking into smaller particles that emit light. Scientists detect this light with special instruments, translating their signals into data that allows them to trace the particles’ origins and, in the process, uncover clues about the universe. To Lina and Neriman, the idea that distant galaxies, black holes, and even the sun could be measured and studied was exhilarating.

“Honestly, we didn’t know much about cosmic rays at first,” Neriman admits. “But once we learned more, we were all in. We loved the idea.”

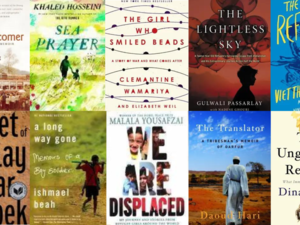

At the University of Utah, Lina and Neriman build cosmic ray detectors (pictured) to collect data and explore how particles from space interact with earth.

With the support of REFUGES and partner programs at the University of Utah, the sisters designed an original research project: “The Effect of the Moon on Cosmic Ray Detectors.” They investigated whether the moon’s position influences the rate of cosmic rays reaching Earth’s surface, deepening their skills in data analysis and the scientific method. Their work culminated in a presentation to undergraduate physics students, a moment that not only solidified their confidence as scientists but also marked a turning point in how they saw themselves in the world of STEM.

That transformation reflected the broader impact of REFUGES, something program manager Ricardo Gonzalez has witnessed time and again. Working closely with Lena and Neriman, he saw their growth firsthand. “It’s been good to see them grow, in terms of their academic endeavors, and then all the stuff that we worked on together has been awesome,” he says, noting how opportunities to engage in research can open new doors for students.

For Lina and Neriman, stepping into science means stepping into spaces where people like them — young refugee women — are often underrepresented. “Being a woman in science, to me, means that you’re pushing boundaries,” says Lina. “Any of us can be scientists. Breaking those stereotypes is the most important thing.”

“Being a woman in science is really important for us because we have to represent our communities… We need to prove to them that any one of us can do it.”

To young refugees and girls who might be unsure of their path, Lina and Neriman offer simple but powerful advice: Take the leap. No matter your background, reach for the stars.