'I have seen first-hand how children's education has suffered'

'I have seen first-hand how children's education has suffered'

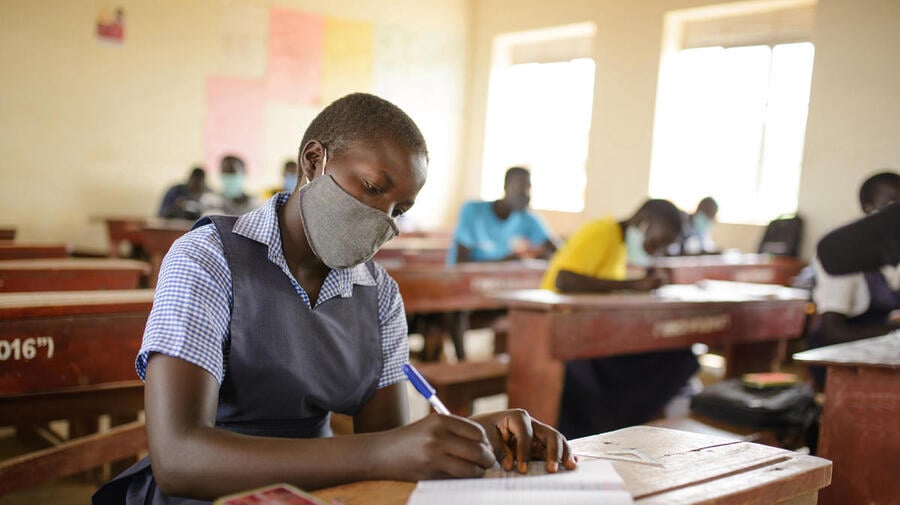

A South Sudanese refugee student attends primary school in a refugee settlement in Uganda.

Young people tell me again and again what keeps them from school: a shortage of materials (books and pens), long walks to reach the school; they are hungry.

In the Palabek refugee settlement in Uganda, I have seen first-hand how children’s education has suffered since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. After two years of school closures, only 44 per cent of school children in Palabek returned to school when it opened, according to Lazar Arasu, director of Don Bosco Catholic organization. The majority of children in child-headed families are unable to return to school at all. Although Uganda’s Universal Primary Education policy stipulates free compulsory primary education of good quality for all children, hidden costs to accessing education remain. Parents are compelled to cover the costs of scholastic materials, school uniforms, and examination fees. For many families, including those who have been forcibly displaced, covering these costs is impossible.

Since its inception in April 2017, the settlement has had only one secondary school, yet the school is not strategically located. Many students must leave home at 5:00 a.m. and walk more than 10 kilometres to reach it. Due to a lack of funding, food rations given to the most vulnerable refugees have been cut 30 to 60 per cent in Uganda, so many students leave without taking breakfast and stay in the school hungry until they return home at 5:00 p.m. There are often no lights to read books or do homework at night. Some students cannot afford books or even pens. So many perform poorly and many drop out.

As a refugee student who is passionate about community service, I have always volunteered as a community mobilizer, social worker, and youth leader. I also joined several trainings, including basic video advocacy training, which later motivated me to advocate for the rights of my community. My dream was to go to university. I was so excited to receive the DAFI scholarship from UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. The scholarship, funded by the German and Danish governments, was based on my academic excellence, leadership potential, and my engagement with the community. After I joined university, I wanted to support my fellow young refugees in the settlement. I founded an organization, The Leads, whose goal is to reverse the worsening school dropout rates and empower refugee children and youth to achieve their dreams. Currently, we are supporting about 120 students with pens and books, mathematics and English lessons as well as motivating them and providing information on higher education opportunities. UNHCR has provided some funding to my organization.

Forcibly displaced people too often find themselves at the centre of international debates, while being left out of them. One thing that motivates me is knowing that the voices of the people most impacted by global education policies and programmes have been chronically under-represented at decision-making levels. Goal 4 of the Sustainable Development Goals, set out by the UN, states that we must ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. It adds that, by 2030, we must ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes. According to Yasmine Sherif, director of Education Cannot Wait, “educating girls, especially those left behind in crises, is critical to the COVID-19 recovery plan, to mitigating climate change, and to ensuring equal and prosperous societies”. For refugee children, especially girls, school is not just a place where they go to learn, it also provides structure and a refuge from the harshness of life outside. As a refugee, I understand this. In fact, refugees who have experienced the life changing effects of school often have the best ideas for reaching the goal of quality education for everyone.

"Refugee children are five times more likely to be out of school than non-refugee children."

UNHCR advocates for education systems that include all, including those who have been forcibly displaced. The Agenda for Protection, and the subsequent Action Plan approved by the Executive Committee in October 2002, especially underline the importance of “education as a tool of protection”. And yet the problem I see in Palabek Refugee Settlement is unfortunately not an anomaly. Refugee children are five times more likely to be out of school than non-refugee children. For those children who can access education, the quality is often very poor. Most of the world’s refugees live in low and middle-income countries whose education systems already struggle.

According to UNHCR’s recent education report, enrolment in primary school is only 68 per cent globally and drops dramatically to 37 per cent at secondary levels. Girls are at a particular disadvantage; in Eastern and the Horn of Africa, only five girls are enrolled for every 10 boys. Currently, in Uganda, 53 per cent of the primary-aged and 92 per cent of the secondary-aged children are out of school. Nationwide in Uganda, there are still sub-counties without a secondary school, including where refugees are hosted, and only 18 secondary schools in 12 refugee-hosting districts. I have made it my mission to reverse these trends.

Thousands of vulnerable young people in Palabek and around the world await our collective action – so that they are not left behind and can achieve their dreams of becoming doctors, teachers, engineers, and more. Many, like me, want to become positive change-makers for themselves, their families, their communities, and our world. I will not give up on them – I have been in their shoes.

Opira Bosco Okot is the founder of The Leads, an organization based in Uganda that strives to keep refugee children and young people in school. He was a participant in the UNHCR Journalist Mentorship Programme, a project created to support refugees, internally displaced and stateless people who want to tell the important stories of today.