Angolan refugees in Congo sign up for voluntary return

Angolan refugees in Congo sign up for voluntary return

Displaced Angolans returning on their own to Kiowa village in Angola, near the Congolese border.

KIMPESE, Democratic Republic of the Congo, May 26 (UNHCR) - After 27 years of war in their homeland, Angolan refugees in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are moving a step closer to home as UNHCR today began registering and signing them up for a voluntary repatriation set to begin next month.

Working together, the UN refugee agency and the DRC government on Monday began a registration exercise in two camps - Nkondo and Kilueka - in the eastern province of Bas Congo that will tally the total refugee population, make lists of those who want to go home over the next two years, and issue identity cards to those who wish to remain for now. Later this week, the registration will extend to Angolan refugees in camps in Katanga province, followed by those based in the capital, Kinshasa, and those who have settled in Congolese towns and villages.

"This is important not only for the Angolan refugees who want to go home, it is also for better protection for those who remain," said Yvan Serge Kragbe, the UNHCR registration officer who is leading the exercise. "If they have ID cards, the police and everyone know they are refugees, and sometimes the ID card allows them to work because it's like a residence permit, it confirms their legal status."

But the buzz in the camps is more about the possibility of going home after the end of the 27-year war in Angola. "Everyone wants to register to return home quickly," said Pedro Agostinho, president of the refugee committee in Nkondo camp. "After the peace accords, everyone was following developments and we knew there was no more war at home. We began to hope to go home and contribute to the development of our country."

Under a tripartite agreement signed between the DRC, Angola and UNHCR last December, the voluntary repatriation of some of the 170,000 Angolan refugees in the DRC is to begin on June 20 and run for two years.

Up until last year, an estimated 450,000 Angolan refugees lived in countries bordering Angola, with another 50,000 scattered across the world. Some 130,000 of them have returned spontaneously since Angola's civil war ended in April last year.

Many of the refugees were born and have grown up in exile; few have any illusions about the difficulties of starting life anew in their homeland. "I don't think life will be rosy at once," concedes Agostinho, who, at 50, has concrete memories of the country he fled. "It will be difficult, but people will help us so that we have time to find stable employment."

Since most of the residents of Angola are themselves former displaced people who went back on their own, he anticipates they will understand well the problems of the new returnees from the DRC.

Antonio Nelson, 62, vice-president of the Nkondo refugee committee, doesn't mind that life will be difficult at first: "The reconstruction of the country depends on the efforts of every citizen. I will do everything for my country and to improve the life of my children."

The sentiment is echoed by 70-year-old refugee Emmanuel Taverest: "I have information coming from the Angolan government that there are roads that aren't good. There are problems. But they say it is us who should build the country and I think that's true."

Even though there is excitement among refugees in Bas Congo about the imminent end of their exile, there is some reluctance to be on the first convoy on June 20. "I don't want to be the first but I also don't want to be the last," said Agostinho.

Other refugees have personal reasons for not rushing to the front of the queue: A 34-year-old mother holding her three-month-old baby girl doesn't want to leave Nkondo camp until she completes her post-natal care. A 62-year-old woman wants to harvest her crop of peanuts before moving out of the camp. Refugees from Angola's Mbanza-Congo province are more eager to go home than those from Uíge province because of damage to an important bridge and roads in Uíge province that would make the area hard to access.

At Kilueka refugee camp, workers are making preparations for the movement of large numbers of refugees when the voluntary repatriation gets under way. The reception centre that welcomed the refugees when they arrived at this camp in 1999 is being rehabilitated to serve as a departure hall. Special pens are being built for the animals the refugees will take home - goats, sheep, pigs, chicken and ducks.

The first wave of the voluntary repatriation from the DRC targets refugees from the northern provinces of Angola bordering Bas Congo, which leaves one refugee wondering where he stands. "No one is talking about repatriation to the south, where I come from," said Domingo Handa, 37, who heads a family of 10 at Kilueka camp.

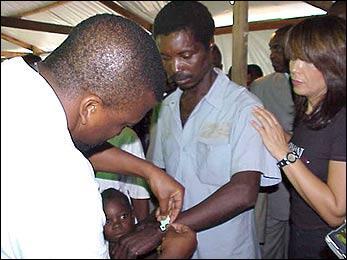

Registration for Angolan refugees in Kilueka camp, DRC.

"If UNHCR is disposed to take us home in an orderly manner, we want to go home," said Handa. But he has some qualms: "The war started in the south of Angola and everyone fled. I was outside the country with my family. I don't know the reality of my village so I don't know whether it will be easy or hard to go home. But I don't think it will be easy."

His 26-year-old wife Maria Matadi, cradling her small baby wearing a green crochet hat, voices with her fears: "I am in agreement with the repatriation. But I was born after the war started. We fled as children and grew up in exile. Tomorrow if I go back to Angola, I will go to the transit centre. But after that where will I go? I don't even know which is my home village anymore."

It is just one of many issues that will need to be sorted out as UNHCR begins to write the final chapter for one of Africa's longest-running refugee sagas.