Drawn home to a land of peace and red lizards

Drawn home to a land of peace and red lizards

Although many Somalis are eager to return, children like this girl in Aisha camp recognize the benefits -- especially the free education -- they received in the refugee camps in eastern Ethiopia.

AISHA REFUGEE CAMP, Ethiopia, March 4 (UNHCR) - When Barkad Omer Alale fled the civil war in his homeland, Somalia, "there were bullets flying all around."

During 15 long years of exile, his dream was always to go home. "Now there is peace there," he says of north-west Somalia. "I am old now and I want to live the rest of my life there."

Abdi Mohamed Hussein, a small boy who looks about 10, but claims to be 13, also talks of "going home" to the self-declared (but unrecognized) independent state of Somaliland in north-west Somalia, a place he has never even seen.

Born in Aisha refugee camp, he says of his homeland: "I want to return." Return? "That's the word my parents use. It is my country. To live in my country is better."

Old and young, the remaining few thousand Somaliland refugees in Aisha are going home in the next two months, bringing to over one million the number of Somali refugees who have returned home from exile, half of them with assistance from the UN refugee agency.

With their departure, UNHCR's eastern Ethiopia operation - once one of the largest refugee-hosting areas in the world with some 628,000 Somali refugees in eight camps - comes closer to winding down. Aisha camp is scheduled to close by the middle of this year, and only Kebribeyah Camp will remain, housing about 10,000 refugees from central and south Somalia who cannot return because of continuing lawlessness there.

Although unfortunate ones may remain in exile for two decades or more, refugees around the world almost always fervently want to go back to their own countries - as long as there is peace at home.

And the Somalilanders in Aisha are no exception. "I want to return to my own country. They were fighting before, but it is safe now," said Halima Ilmi, a 38-year-old refugee woman who left the camp at the end of February on a UNHCR-organized convoy, together with her husband and their seven children. "We are going back to start a new peaceful life. I am happy finally to be able to go back."

Like so many Somalis who have gone to north-west and north-east Somalia (also known as Puntland), she is prepared for the hard work of rebuilding her family's life, and the economy of the country. She hopes to become a trader or shop owner to support her family.

She realizes life will be difficult in one of the poorest corners of Africa, where almost half the population lives on less than $1 a day, but she says confidently: "Once we go to a peaceful place and we are healthy, there will be no problems."

Six of her seven children were born in the refugee camp and "they are very excited," she said shortly before boarding the convoy bus home. "They have never seen Somaliland, but they have heard a lot. I have told them about every mountain, every hill, every river, every insect. It won't be a foreign country to them."

Although the border here between Ethiopia and Somalia is unmarked - locals recognize it because of a nearby hill - Somali refugees in Aisha have a keen sense that they are away from their own country.

"Refugee?" says a teenage boy from Mogadishu. "The word itself is not good. Who wants to be a refugee?"

Young Abdi, the one who says he's spent all 13 years of his life in the camp, sees Somaliland through the eyes of his older sister, who was no more than five when she fled with their parents. "She told me that while looking after the goats, she saw different types of lizards. Over there, they have red lizards."

Similarly, 15-year-old Mohamed Hirsi Jama is convinced that his "home town" of Harrirad, just 3.5 km inside Somaliland from the border, "doesn't look like this. It's hilly and the houses are different. I will be happy to be in my own country."

Despite the safe refuge he has found in Ethiopia, "this is not my land, and I know it's not my land. I have to return home."

At the height of the Somali crisis in the early 1990s, nearly half the country's entire population of 7.5 million was displaced - either within Somalia or as refugees elsewhere.

During the 1990s, many came home on their own, even before UNHCR started assisting their return in 1997. There are still some 350,000 Somali refugees in exile worldwide, mostly in nearby countries. There are also estimated to be as many as one million Somalis who are not registered as refugees, but who live abroad.

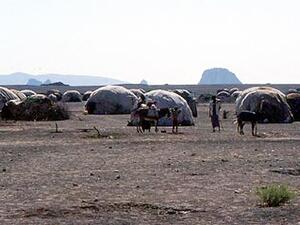

As the last Somalilanders go home from Aisha, the camp is shrinking. Refugees cart away scarce building materials such as tree trunks and cardboard cartons to reassemble their tukuls (traditional dome-shaped huts) at home.

On a recent convoy, returnees hired herdsmen to walk their 60 donkeys across the border, and their 120 goats were put on UNHCR trucks to join the procession of six passenger buses and 46 trucks (carrying 451 people) bound for Harrirad. The UN refugee agency gave returnees plastic sheeting, blankets, jerry cans, kerosene stoves and nine months' supply of food to help them settle in back home, as well as a transportation allowance in case Harrirad was not their final destination.

The refugees' joy at going home has been matched by that of UNHCR's Ethiopian employees, some of them former refugees themselves who, ironically, once found safety from Ethiopia's political upheavals inside Somalia.

"I feel happy to see these people go back to their homes," said Mohammed Tahir Garse, a UNHCR field assistant who has worked in six of the eight Ethiopian camps for Somali refugees over the past 15 years.

"These people have stayed out of their country for 15 years. We have given them protection, and the government of Ethiopia has given them protection," said Garse, who has had his life threatened by bandits four times while carrying out his UNHCR duties in eastern Ethiopia. "Now the time is right for them to go home. People can't be refugees forever."

By Kitty McKinsey in Aisha Camp and Harrirad, Ethiopia