A ray of hope from Colombia's badlands

A ray of hope from Colombia's badlands

BARRANCABERMEJA, Colombia (UNHCR) - Colombia's foremost writer Gabriel García Márquez ends his novel, "Love in the Time of Cholera", with a memorable scene: the hero, after waiting a lifetime for his childhood sweetheart, invites her on a river cruise. In order to be alone with her, he persuades the ship's captain to fly the yellow flag that warns of the presence of the dreaded disease on board. Undisturbed, the two elderly lovers are able to consummate their love while sailing slowly up and down the great Magdalena River, which, from South to North, flows through the heart of Colombia.

Today the Magdalena, badly polluted with urban sewage and industrial waste from Colombia's petrochemical industry, is far from being the perfect background to an old-fashioned romantic story. Instead, the region of the Middle Magdalena has been the scene of some of the worst human rights violations perpetrated in a bloody conflict that made news headlines recently with the massacres at Bojayá.

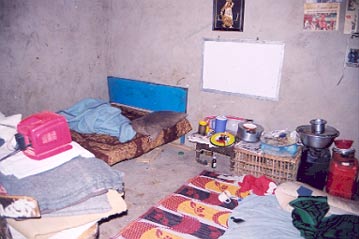

Fighting between left-wing rebel groups, right-wing paramilitaries and organised crime syndicates has forcibly displaced as many as 2 million people within the country since 1985. Many internally displaced persons (IDPs) have moved from the countryside to the grim slums that surround Barrancabermeja, the region's main city.

"People don't want to move unless they start killing people, then we run away," said a displaced Colombian in a nearby settlement, speaking on the condition of anonymity. "The 'paras' [paramilitaries] kick all those they don't like out of town. Many IDPs come but they don't register with anybody because they are afraid or they simply don't know."

Barrancabermeja's shantytowns used to be a stronghold of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) until the paramilitary Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) wrestled control of the city from them through a spate of savage killings, death threats and forced expulsions in December 2000.

These are Colombia's badlands. They are still predominantly rural, but accelerated unplanned urban development, combined with forced displacement, have led to chronic overcrowding and other social problems in the towns and cities. They have also led to unequal land and income distribution in the countryside. Of the illegal armed groups now taking part in the Colombian conflict, two originated in the Middle Magdalena region: the AUC and the left-wing National Liberation Army (ELN), who are still active around their stronghold in the San Lucas mountains.

In the small settlement of Carmen del Cucu, close to San Pablo on the west bank of the Magdalena River, a group of 26 families have returned to their homes after being displaced by the conflict two years ago. They formed a Producers' Association, which has started a project to grow rice. UNHCR is helping them through its Barrancabermeja office and the Parish of San Pablo. A tractor has been hired to clear the land, and seeds and tools have been distributed. A threshing machine for the rice is on its way.

"Other people around here will also plant rice now that they know the threshing machine is coming," said José Natividad Ortega, a former IDP and now President of the Producers' Association. "UNHCR has not forgotten us. Now we have hope and we are working tooth and nail to improve our lot here."

UNHCR's Field Officer Antonio Menendez explained, "The idea is to help people work together to recreate a spirit of community and, at the same time, to contribute to food security."

Carmen del Cucu is not the only place where displaced people have organised themselves to improve their lives. In Yondo, just across the river from Barrancabermeja, some 1,000 IDPs from more than 190 families have formed an association to defend their rights. With help from the local municipality, the association was able to buy a plot of land that became a small farm called La Esperanza ("hope" in Spanish).

Many of the families involved are headed by women. "Women IDPs are the most enthusiastic about the farm," said UNHCR's Menendez. "For them it is not only an opportunity to work and receive an income, but also something to hold on to and feel responsible and proud about."

The UN refugee agency and its operational partners have been supporting the work of La Esperanza by developing income-generating projects on the farm, including raising pigs, planting vegetables and fruit trees and breeding fish in a pond. About 30 families work directly in the implementation of these projects.

Still, life is tough in Yondo. Most of the settlers do not manage to meet even their basic needs. Many of them live in constant fear of illegal armed groups operating in the area. Some, accused of supporting rival armed groups, are discriminated against.

But they have not lost their dignity and, with UNHCR's help, they are working hard at rebuilding their lives. After all, if love can flourish even in the time of cholera, hope can also survive in the Middle Magdalena during these difficult times.

By William Spindler

UNHCR Caracas