Congolese woman in exile seeks to write wrongs

Congolese woman in exile seeks to write wrongs

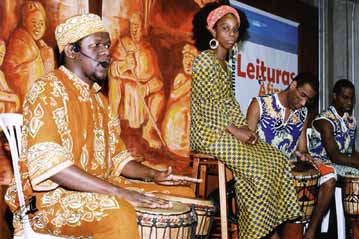

LONDON (UNHCR) - Standing on a podium on the eve of World Refugee Day, a confident woman with brightly-dyed red hair read extracts from her novel. Amba Bongo, a member of Exiled Writers Ink!, held the London audience in thrall as she related her abduction by the Congolese military.

Together with two other refugee women writers, Amba was speaking at a UNHCR literary evening on June 19 to celebrate the achievements of refugee women. Through their stories, the writers infected the audience - representatives from the government, non-governmental organisations, and other refugees - with their spirit and determination.

Amba, a single mother, has overcome great odds to get to this stage, guided by a belief that she could rise above difficult situations with dignity. "I had to be so strong," she says a few days later in her flat, cuddling her second child Andrea, aged one.

Not only is she the proud author of "Une Femme en exil" - "A Woman in Exile" - based loosely on her experiences, she has also managed to set up an organisation called Active Women, aimed at helping her fellow Africans.

Brought up in a prominent family in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Amba was sent to Belgium for a university education in 1984, like her father in the 1950s. She gained a degree in psychology at Mons and returned to Kinshasa under then-President Mobutu Sese Seko. She found a rewarding job in the university and settled down happily with her young daughter Nathalie, secure within a circle of loving relations.

But when a corrupt new director with powerful connections was appointed to her department, Amba was horrified at his misuse of the funds and, bolstered by her involvement in the Congolese Women's Movement, reported it.

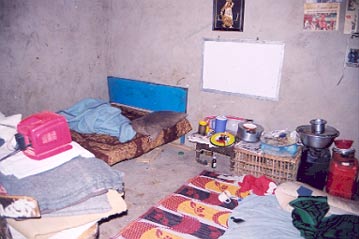

A few weeks later, in May 1991, the military came for her. She spent five months alone in a cell, suffering the taunts of her former boss and tortured by the guards. "Sometimes I can still smell that horrible smell, it's urine, it's grease, it's dampness," she says in disgust. Luckily, she caught the attention of a guard who was involved in helping prisoners to escape and they planned a dramatic breakout.

He dressed her in a military uniform and she ran through the jungle in the rain to Kinshasa, stumbling in boots three sizes too big. Knowing that her tormentors would come after her, her parents contacted an agent. Amba was given a day's notice and packed on a plane to England. She did not know it then, but she would not see her daughter for another six years.

Amba's European education and good spoken English gave her a head start in London, but the trauma she had suffered and the separation from her family affected her deeply. "I was full of anger," she recalls. Depressed, she spent three years hiding in her room.

Anxious about her asylum application to the Home Office, she called them repeatedly, only to be told, "Your application is being processed." In fact, she says, it took eight years to attain refugee status, and six years to pay for her child to come to England. This was very difficult for her, she says, shaking her head. "When I left her, she was seven. She joined me when she was 13. She wasn't my daughter any more, her grandparents were her mum and dad."

Others in the same situation urged her to try to get around the law. "Everyone was telling me to get pregnant so I could get a flat, but this is not a reason to have a baby! Everyone was telling me to buy a French passport or marry someone from a French Caribbean Island. But because of my upbringing and because I knew I would emerge from this situation, I held firm."

Striking out by herself, she managed to find a flat and began vocational training in Business Administration with Languages in 1993. "I got so much bad advice here. People from my country told me that I wouldn't get a good job because I am black. They asked me why I was going to college and told me I should become a cleaner. But I didn't want to."

A year later, Amba started applied for jobs, but without much hope. To her surprise, she eventually got a job filing at Eurotunnel. "I had an office. Oh my God, my friends used to come and see it. I used to say, 'Look at my chair.'"

In 1995, she decided to move into areas that really interested her, doing some interpreting and working with members of her community. It was around this time that she began to beat her depression. "I realised that I was so lucky. I saw so many people from my country dying from AIDS and with much worse stories than myself."

Inspired by her previous work with the Women's Movement in the DRC and driven by a desire to make good advice available, Amba set up Active Women in 1998 after several setbacks. The non-profit organisation is currently run on a voluntary basis, but she is looking for funding and is full of plans. Active Women offers basic counselling, information and advice on immigration, housing, education, health and the welfare system.

Amba says she is worried by the lack of knowledge some of the Home Office's interviewing officers have about countries and their systems. "Sometimes they don't believe my clients if they say they bribed guards to get out of prison. They think it is not possible," she says. She is also concerned about the treatment of clients who claim they have been raped, arguing, "It is so hard already to tell someone you have been raped. You don't want to talk about it. Then to be told that they don't believe you, it is so frustrating."

There is one piece of advice close to her heart that Amba always offers her clients. "I tell people to have friends in all the communities to see how they live, because when I came, I didn't have good advice to give me alternative ideas."

To her, understanding different cultures is also key to reducing tensions between the British and asylum seekers. "I can understand why the British are hostile. I can put myself in their place. At home I was suspicious of people coming to the Congo and getting rich, but this is all about a lack of knowledge. When you don't know other cultures, or even the people living near you, you are scared and you feel invaded. This is a normal reaction, but I feel people have to make the effort to get to know the culture or the person. I have British friends and I believe in integration and getting to know others. It helped me grow as a person and become less judgemental."

Writing her book also helped Amba get over her trauma and increase her confidence. "It was a good experience for me. I always liked writing. I buy expensive pens - for me, it is like buying perfume."

When she was in her 20s and 30s, she wrote detailed letters to her father about her life, but it was not until she turned 35 that she began writing "Une Femme en exil". Encouraged by her father, a former editor, and helped by a Congolese critic based in Paris, she sent her manuscript to L'Harmattan, which published it almost immediately, in 2000.

"I haven't got any money yet," she says ruefully, "but I write for myself anyway."

When Amba talks about the DRC and the family she has left behind, her eyes light up. "I really want to take Active Women back to the Congo. I'm asking [British charity group] Comic Relief for funding as it often supports projects in Africa. I hope I'll be all right. After all, I've been away for a long time and this is something that will benefit the Congo."

By Ursula Woodburn

UNHCR London