Feature: Proposed US-Canada accord sparks debate

Feature: Proposed US-Canada accord sparks debate

OTTAWA (UNHCR) - Buffalo, New York, is known for its frigid winters and record snowfalls. Plattsburgh, New York, is a peaceful town on the western shore of Lake Champlain. Neither place is normally associated with refugees. But both are at the heart of a heated debate in North America about how to handle asylum seekers.

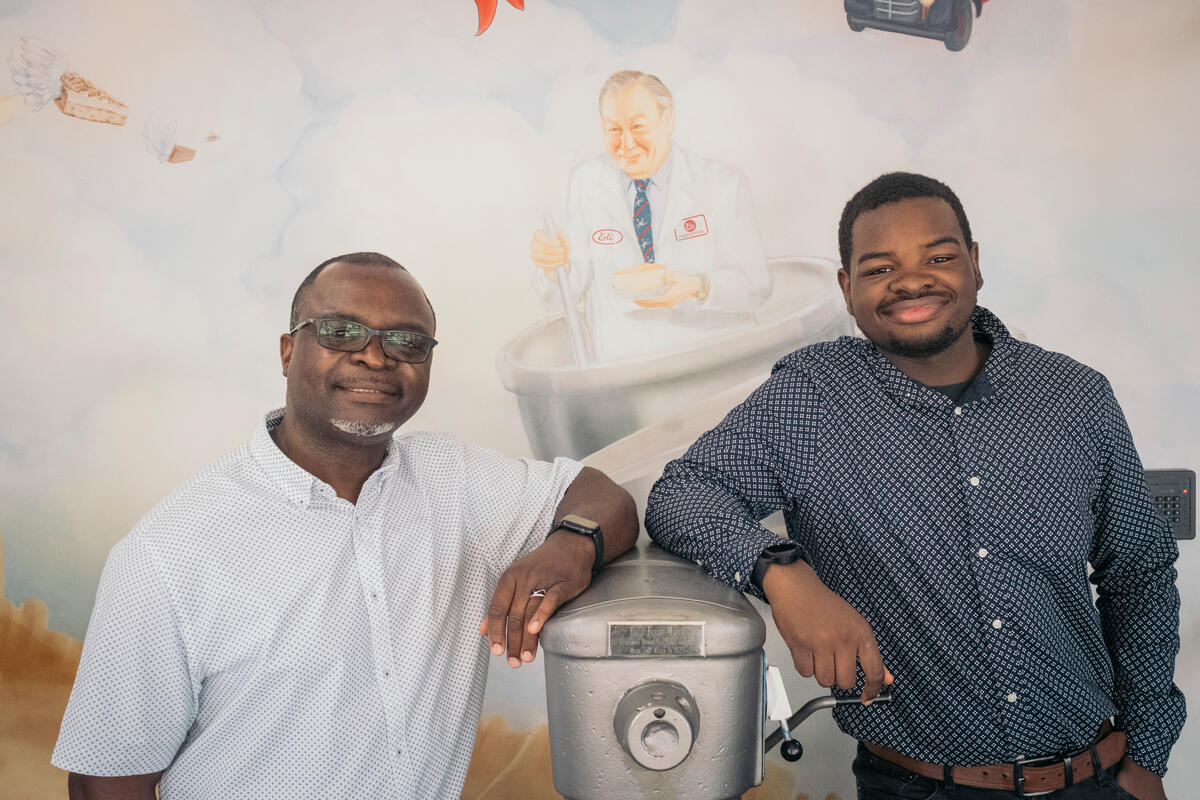

At a shelter in Buffalo run by a non-governmental organisation (NGO) called Vive la Casa, asylum seekers from around the globe prepare to make their way to the Canadian border. The Salvation Army in Plattsburgh also saw a surge in asylum seekers needing assistance earlier this summer. Vive's website explains that it provides "shelter, health, legal and other essential needs for refugees fleeing war and persecution who seek asylum and new lives in Canada". Now they are afraid that this possibility will soon disappear.

Since the mid-1990s, Canada has been trying to persuade the United States to conclude a "safe third country" arrangement that would require claimants to seek asylum in the first of the two countries they reach. Until recently, there was little US enthusiasm for the idea. Since the refugee flow is mainly from south to north, such an arrangement is likely to decrease the number of asylum seekers in Canada and increase the number in the US. But since September 11, border co-operation and security have taken on new importance, and the arrangement is now part of a larger US-Canadian package, a 30-point "Smart Border Accord".

Last year, over 14,000 people applied for asylum in Canada at a US-Canada land border. This compares to about 200 people who applied for asylum on the US side of the border. In general, it is estimated that over half of all of Canada's asylum claims (both at the border and inland) are made by people who transited through the US. The draft agreement would return many of those heading north back to the US.

The agreement could be finalised as early as September and would go into effect possibly by early 2003. On June 28, Canadian Deputy Prime Minister John Manley and US Homeland Security Director Tom Ridge initialled a proposed draft of the safe third country deal and hailed it as a way to promote the "orderly handling of asylum applications" and to "reduce misuse" of the two countries' asylum systems. But many observers are asking: Will it work?

"Safe third country" agreements have been part of the asylum landscape in Europe since the early 1990s, but they have not worked very well. Europe's 1995 Dublin Convention, which was intended to determine the state responsible for handling an asylum claim, is widely considered not to have been effective. The European Union is still in the process of devising a replacement. Difficulties invariably arise when countries try to assign responsibility for handling claims before agreeing on common conditions of reception for refugee claimants, and on a similar assessment of who qualifies for protection.

The draft US-Canada agreement raises many of the same issues and could be difficult to implement. The agreement allows people who have relatives in one of the two countries to make their claim in that country, regardless of which one they entered first. But a border official will have to decide whether these relatives really exist. This may not be easy, and could result in backlogs of applicants waiting at the border for a decision.

Experts also worry that the arrangement could fuel an illegal industry of people-smugglers who exploit vulnerable people, including asylum seekers, as they arrange to cross the world's longest unmilitarised border clandestinely. This concern stems from the fact that the agreement applies only to claims lodged at land borders, not inland. Once the agreement goes into effect, people seeking asylum in Canada may decide to cross into Canada illegally and submit their claims inland rather than present themselves to Canadian officials and risk return to the US.

Another point of concern stems from the differences in the adjudication of claims and the treatment of refugees in the two countries. In its comments to the two governments on the draft agreement, the UN refugee agency recommended that these differences be addressed in a manner consistent with refugee protection principles. It recommended that asylum seekers who would be subject to the agreement not be placed in US "expedited removal" proceedings, something UNHCR has expressed concerns about the past.

The agency also recommended that possible bars to applying for asylum in one or the other country - such as the US one-year deadline to file an application - be taken into consideration to make sure asylum seekers have adequate access to a fair process.

The detention of asylum seekers, including children, is also of concern. UNHCR reiterated that asylum seekers should not be detained and encouraged both countries to limit the use of detention for asylum seekers to the greatest extent possible, and to avoid the use of local, state or county jails.

"Ultimately our main concern is that people seeking asylum have access to a full and fair procedure and that those who need protection from persecution can get it," said Guenet Guebre-Christos, head of UNHCR's office in Washington, DC.

"Clarifying which country is responsible for determining refugee status is a positive goal and can help prevent asylum seekers being left in limbo because no country assumes this responsibility. But certain safeguards need to be in place under such an agreement to make sure refugees do not fall through the cracks - which in the worst case could mean being sent back to persecution, torture or even death."

While discussions about a possible agreement continue, NGOs near the border express growing concerns about their ability to cope with possibly large numbers of people trying to reach Canada before the deal goes into effect. Rumours about the agreement being finalised in June - which turned out to be unfounded - sparked a rush to the border. The Buffalo shelter took in more than 1,000 people in June, and the Canadian border post at Lacolle, north of Plattsburgh, received around 1,250 claims that month - three times as many as the same month last year. The situation could be even more worrisome should the agreement take effect in the dead of winter, which could leave numerous children and families without shelter in the freezing northern border region.

At the same time, some asylum seekers are continuing their journey northwards, generally unaware of the proposed changes. Whether because they want to join family or community members in Canada, because they speak French, because they missed the deadline to apply for asylum in the US, or because they believe their chances to get protection would be better in Canada, they head north, uncertain of what awaits them. For many, the uncertainty may only increase once the agreement goes into effect.

By Judith Kumin

UNHCR Canada