Sudanese refugee gets a new shot at life

Sudanese refugee gets a new shot at life

KAKUMA, Kenya (UNHCR) - Sudanese refugee Nyankiir Deng is looking forward to a quiet life in Australia. After years of repeated displacement, an abusive marriage and constant harassment, she will have a chance to start her life with her five children under the resettlement programme within the next few months.

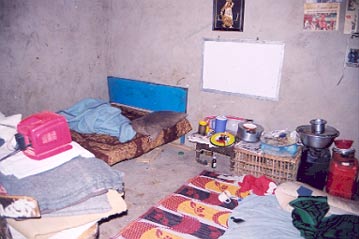

For now, they are living in a mud hut within a protected area of the vast Kakuma refugee camp in north-western Kenya. The older children have stopped attending school and even then, Nyankiir constantly fears for their safety.

At 27 years of age, Nyankiir has been through what most women will never know in their lifetimes, yet she is just one of the many Sudanese women who share similar experiences.

Nyankiir fled her native Sudan in 1987 after government forces bombed her village in what has been one of the longest-standing civil wars in Africa. Together with her parents, two sisters and a brother, she escaped eastwards to Ethiopia where they settled in Funigdo camp. In 1991, with the fall of the Mengistu regime, they were forced back to Sudan.

A year later, another bombing in Sudan sent her family fleeing in different directions. Nyankiir found herself among a mass of people moving southwards into Kenya, where they were received by the Kenyan authorities and the UN refugee agency. Separated from her family, Nyankiir was placed in the care of another family. She was registered as a member of her new family when they were moved to Kakuma refugee camp.

Nyankiir's woes started when as a teenager, she was raped on the way home one night. Too afraid to report the crime, she became withdrawn and dropped out of school. At 16, she was forced to marry into the community of her attacker in order to raise dowry for her foster family's only son. As in many African cultures, when a woman gets married, her husband pays dowry - often in the form of livestock and/or money - in exchange for the bride.

After several years in the abusive marriage, Nyankiir decided she had had enough and wanted a better life. She enrolled for an English course to improve her interaction with other women in the camp, particularly to share her experiences with women of other nationalities. Kakuma camp is home to Burundians, Congolese, Eritreans, Ethiopians, Rwandans, Somalis, Sudanese and Ugandans, all of whom speak a different language. English and French are the only common languages of communication.

From there, she joined a local women's group funded by UNHCR and run by the non-governmental organisation, Don Bosco, to build self-reliance skills. During the weekly meetings, the women also discussed issues that affected them and sought redress through the Women Support group - an initiative to teach women about human rights and better protection, as well as to provide community support to survivors of sexual and gender violence.

When her husband broke her hand in a fight, Nyankiir was taken to the camp hospital by women from this group. She reported him to the police before being referred to a UNHCR lawyer who handles cases of sexual and gender-based violence. Her husband was charged with assault and sentenced to six months' imprisonment, or a fine of 5,000 Kenyan shillings ($66). His relatives paid the fine and he was released.

From then on, Nyankiir suffered daily harassment from her husband and his family. She sought help from the traditional courts, the payams, which referred the matter to another court in southern Sudan for final judgement. Nyankiir was unwilling to go to southern Sudan due to the insecurity and the fact that she did not know anyone there, having lost contact with her family.

Eventually, her husband applied for a divorce and was granted custody of their children because dowry had been paid upon their marriage. Nyankiir lost her home once again, but she was not willing to give up the only family she knew, her children.

With help from the UNHCR lawyer, Nyankiir and her children were moved to a different location in the camp. After a failed kidnap attempt by her in-laws, mother and the children were transferred to the "Protection Area", a fenced-off area beside the police station where high-risk security cases are temporarily housed while solutions to their problems are sought.

The solutions range from arbitration, which sometimes results in reintegration back into the community; to inter-camp transfer to Dadaab camp in eastern Kenya; or resettlement to a third country.

Attempts to reconcile Nyankiir with her in-laws have been unsuccessful as they insist on having sole custody of her five children despite recommendations that they are better placed under her care. Her in-laws insist that if this is the case, they should have a refund of their dowry. But Nyankiir's foster family is in no position to refund the money and has been pressuring her to give up her children.

In view of all these factors, UNHCR decided to propose Nyankiir for resettlement to a third country under the women-at-risk category. After extensive interviews and 13 months of waiting, she was accepted by the Australia government in April 2003, giving her the chance to finally lead a normal family life.

By Rose Kimotho

UNHCR Kakuma