Women refugees in Cairo: In a class of their own

Women refugees in Cairo: In a class of their own

CAIRO, Egypt (UNHCR) - For many of the 3,400 Sudanese refugee women struggling through the tiresome rhythm of Cairo life, their daily routine revolves around surviving the wounds of the past, sustaining a basic living, and anticipating a better future. This routine may change slightly now.

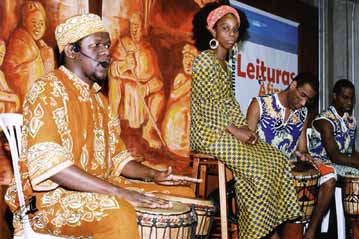

The Sacred Heart Church in Sakakini, east of Cairo, has started a refugee women's training centre within its Adult Literacy Programme - coinciding with a month of activities as Egypt's women's association celebrated International Women's Day on March 8.

This is not the first time the church is working with refugees. It has been the focal point for the education of 2,000 refugee children, as part of the activities of the Catholic Relief Service, one of the major implementation partners of UNHCR's Egypt office.

The UN refugee agency deals with around 11,000 refugees in Egypt, 92 percent of whom are from Sudan.

So far, more than 130 women have enrolled in the women's training centre. An Italian association has donated funds to finance the first term, and organisers say they are looking for more resources to continue with the project.

The initiative is especially important for refugees who see no durable solution in the near future. For refugees in Cairo, as with refugees elsewhere, it takes time for UNHCR to determine their status. In some of the cases, resettlement to the United States, Canada, Australia or any other destination takes around two years. In general, resettlement to the west has become a longer process after the September 11 attacks on the United States.

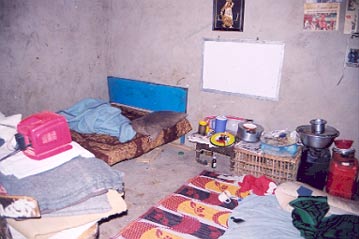

Meanwhile, many of the Sudanese refugee women work without authorisation as domestic help in the houses of middle- and upper-class Egyptians, competing in a labour market that includes hundreds of thousands of Egyptian women. With a monthly salary averaging $90-$150, these jobs give the refugee women the opportunity to survive economically. But the high cost of any kind of formal training in private schools, especially for English-language classes, makes it impossible for them to enrol.

Considering this waiting time, the urge to adapt themselves to a new environment and improve their living conditions, the need for training has risen. Annie Reyes, a volunteer with the Sacred Heart Church, and Sister Mechtilda Mukama, a Canossian sister, were requested to organise a formal education and training programme for these women. The programme offers sewing, beauty, English and Arabic classes, plus courses on primary health and computer skills.

For the refugee women, the classroom is not just a place to learn but also a place to meet other women in the same situation. Asked about her reasons for enrolling in the courses, one of the refugees, Faiza Hassan, says, "Besides learning, this is the best way to know that you are not alone in this very difficult situation."

She adds that learning English gives her more chances for any future prospects, especially in other countries.

For the teachers, who are recruited within the refugee community, this is their best chance to help other refugees while helping themselves at the same time. Tania, a Sudanese refugee with a Master's degree in Business Administration and an excellent command of English, says, "I'd rather teach English to other refugees than continue working as a house help."

The salaries the training centre pays are minimal, but they constitute the sole income for many of the refugee women. Seeing the big number of young children among the refugees, the centre agreed to recruit two baby-sitters to take care of them while their mothers attended lessons. This initiative is crucial for the widows and single mothers who live alone with their children and do not have the support of husbands or extended families.

The courses are almost free, but a minimum charge is requested. For Reyes, the most difficult task is not just to start the project, but to keep it running and to keep the women participating and enthusiastic about it. She says many of the women suffer psychological anxieties caused by their status and hard lives. Therefore, to motivate them to participate actively is "sometimes very difficult," she says.

Still, an air of gaiety fills the place. One of the participants, an old woman who attends literacy classes, points out, "This way, I am waiting for resettlement with optimism and not in idleness."

By Hanzada Fikry

UNHCR Egypt