UNHCR pumps aid where drinking water is rarer than diamonds

UNHCR pumps aid where drinking water is rarer than diamonds

KOIDU, Sierra Leone, Aug 25 (UNHCR) - The name Kono is synonymous with diamonds and the district has arguably been called the breadbasket of Sierra Leone. To some Sierra Leoneans, Kono district is the country's hope for development while others see it as a land of mixed blessings. Whatever their persuasion, the harsh fact is that Sierra Leone has consistently been ranked at the bottom of the UN Human Development Index Report, four times in a row.

Koidu, the main town in Kono district, is situated in eastern Sierra Leone, some 320 km from the capital, Freetown. Visitors taking the six-hour drive from Freetown to Koidu do not feel like they are heading towards one of the world's major diamond-producing zones. Instead, some may feel that they are hurtling towards doom.

"Kono became central in the war because whoever controlled the district controlled the diamonds, which both the government and the rebels needed in order to procure more weapons to continue the war," said Tamba Boima, UNHCR's protection assistant and a native of Kono.

He said he could not remember the number of times the district was attacked before it finally fell to the rebels of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) on October 30, 1992. Sierra Leone's decade-long civil war ended in 2001.

Before the war, Kono district had about 500,000 people and its population now stands at approximately 350,000. The UN refugee agency has repatriated over 90,000 refugees to this eastern district since 2002.

Today, Kono remains a ruined land with crippling poverty and crumbling infrastructure. Most of the people live in makeshift houses covered by tarpaulins supplied by UNHCR as part of the return package. The district has had no electricity since the only National Power Authority in the district collapsed in 1984. It also has no pipe-borne water.

"The systematic destruction of houses and other public infrastructure, exacerbated by rampant diamond mining activities, left the entire district in ruins," said Chief Kai Musa Kamara of Tongoma village. "All water pipes were damaged by miners in their exploration for diamonds."

He added that most of the other towns and villages outside Koidu have never had pipe-borne water or any proper system of water supply. As a result, local inhabitants, mostly returnees from Guinea, have been drinking water from unsafe traditional wells. This has increased the rate of water-borne diseases like cholera and dysentery, which claimed the lives of many returnees in early 2000 and 2001, said Chief Kamara.

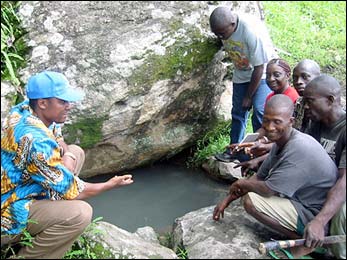

To illustrate his point, the chief took staff of UNHCR and partner agency Peace Wind Japan (PWJ) to an old traditional well situated in a bushy swamp near Tongoma village. The open well looked clayish and had many frogs singing in it.

"Because of the milky colour of the water, we used to invoke the name of the Lord and close our eyes before drinking the water," said Chief Kamara, explaining the local belief that this would protect them from disease and evil.

But things have improved after UNHCR, PWJ and WVI (World Vision International) provided 37 pump wells to more than 20 villages in Kono district. Such wells have also been built in Koidu town's government hospital, police barracks and a local community called Lebanon.

"Pump wells are safer because the water is situated in the second or third layer of the ground, which protects it from pollution. It is also a reliable source of water because the pump well never gets dry, whereas open traditional wells can be easily contaminated and can dry up in the dry season," said PWJ's water engineer, Laurent Heritier.

"We have had cause to provide a second pump well in villages where there is a significant increase in population in order to reduce pressure and make water more accessible to the people," he added. "Over 200,000 people can now access safe drinking water in many parts of the most remote areas of Kono district and the pump wells will serve the communities for as long as it is possible."

In Nyamadu village, the traditional well is situated about 500 metres from the village. "Fetching water at night was strenuous and very risky, especially for the children, who faced the risk of stepping on reptiles and dangerous insects," Town Chief Aiah Moigwa of Nyamudu said of life before the pump well.

"We must ensure proper management of the well to discourage misuse," said Chief Moigwa. "We close the tap during the day when everybody goes out to work, reopen it in the afternoon to allow the women to cook, and close it again at night."

Paul Longwe, who oversees UNHCR's field office in Koidu, noted, "In the villages, the popular name for PWJ is 'water'. We are very much appreciated by the local communities here. They are keen to keep talking about what would have happened in the district had we not provided them with safe drinking water."

Another 20 pump wells will be constructed by the end of the year, bringing the total number to 57. Of the 1,000 community empowerment projects implemented by UNHCR in Sierra Leone, Kono district accounts for 292. The projects involve water, sanitation, health, education, road rehabilitation, skills training, micro-credit and agriculture.