People power rules for Liberian returnee community

People power rules for Liberian returnee community

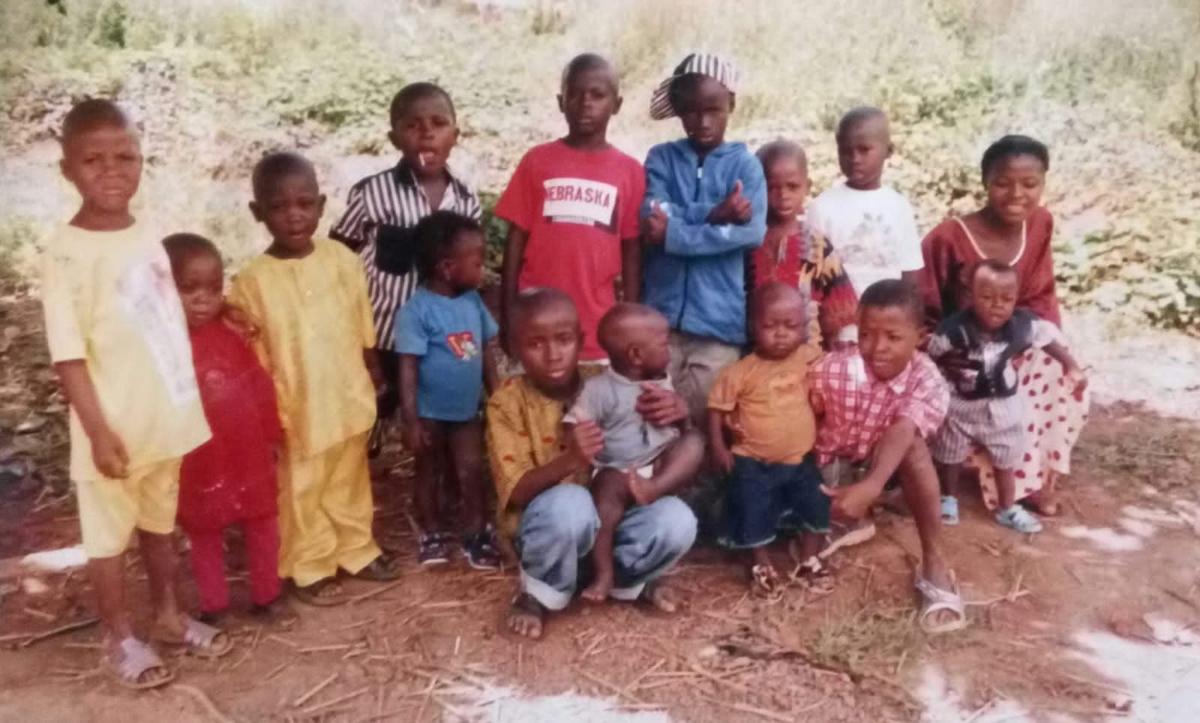

BOIWEN, Liberia, August 11 (UNHCR) - It's a sunny morning, and the public school benches in a remote village in Bomi county of western Liberia are crowded. Children aged between three and 12 sit side by side in the front rows, while their parents squeeze themselves on the back benches. Expectations are high as a wide range of entertainment awaits them, including speeches, drama, songs and recitation.

The residents of Boiwen town have come together to celebrate many things - the completion of the school building, the end of the academic year, the progress of their children, the hard work of the town's three voluntary teachers, and basically their restart as a functioning community in war-torn Liberia.

During the 14-year civil war, Boiwen - located about 3 km from the main road between the capital Monrovia and Tubmanburg - was caught in the fighting, including an attack by rebels of the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD). The town's residents fled together, most of them ending up in Wilson Corner camp near Monrovia.

The conflict ended in August 2003, and Boiwen's residents decided to come home together this year. Today, the town acts as an administrative centre for five other towns and seven nearby villages.

Boiwen and its sub-towns have done extremely well and set an example for other villages in Liberia. Yet, the secret of their success is as old as human societies - meticulous traditional structures were put back in place.

Wilson Mambu, the community mobiliser, has been chosen by UNHCR's implementing partner, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), to survey the development of the 12 communities. He cycles every week through the district to count people, take note of their needs, liaise between village chiefs and UNHCR, provide basic information on how the agency's community empowerment projects work, and last but not least, to "mobilise" the communities to engage themselves in rebuilding their destroyed villages.

Mambu opens his exercise book, where he is recording every single movement with scrutiny. "So far, we have a population of 1,896 people in the area - 200 displaced people came back with a ticket, and 1,696 came back on their own," he explains. "Boiwen town itself has 575 citizens. During the war only 100 people stayed here." A few hundred are still missing.

Those who returned "with a ticket" took advantage of UNHCR's assistance and were provided with relief items, four months of World Food Programme rations and transport allowance to come back. Though UNHCR does not have the explicit mandate, it committed itself in 2004 to assist 250,000 internally displaced people with the same return packages Liberian refugees receive when they come back through voluntary repatriation from neighbouring countries. So far, close to 200,000 internally displaced Liberians have received assistance and returned to their places of origin.

Once back in their communities, the displaced people benefit from the same reintegration projects UNHCR has set up for returning refugees. The Boiwen community, through its chiefs, applied for assistance in the form of a palaver hut, a water well and latrines, as well as community farming tools and seeds. The three projects are all completed, and farming will continue in October, after the rainy season.

For now, Boiwen needs no national police station or magistrates. Every decision is taken by the community itself, represented through district and town chiefs, as well as a dedicated committee for every issue. The Town Development Association decides on what to rebuild first, the Hygiene Education Committee takes care of environmental issues and the cleaning of the villages, the Water Committee organizes supervised "opening hours" at the water well in order to keep playing children away from the well, and the Women's Group of Boiwen gathers regularly together to talk about domestic and education concerns.

"Our next project is to hold a workshop on domestic violence and sexual and gender based violence," says NRC's Richelieu Wollor. "We train a group of people and they sensitize the communities."

So, step by step, Boiwen is becoming again what it was before the war: a normal town in Liberia.

Meanwhile, at Boiwen's public school, the audience is following a drama staged by seven school children. They address a delicate issue: Some people seem to be stealing cassava leaves from their neighbour's plantations. "I'll kill that man!" shouts one of the young actors, while the other one, playing the town chief, looks for a fair and non-violent solution.

At the end of the play, the thief apologizes and promises to pay for the stolen goods. The audience is delighted. "There are always some people who want to live on the expenses of others who are hard working," says principal teacher Blamah Sinnah. "Of course we also have such people among us. But we don't solve these conflicts by killing each other anymore."

He adds, "Today most of our children are back in school. We don't hear the sound of bullets anymore. This alone is remarkable. And when cooperation is there, development will certainly follow."

By Annette Rehrl

UNHCR Liberia