Between the devil and the deep blue sea: mixed migration to Europe

Between the devil and the deep blue sea: mixed migration to Europe

LAMPEDUSA, Italy, October 5 (UNHCR) - Vincenzo Mulé has seen a lot of drama on the high seas during his years with the Italian coastguard, including shipwrecks, massive storms and dramatic rescues. But one incident sticks out in his mind.

"It was about two years ago," he recalled during a recent interview on this island located midway between Sicily and North Africa. "There was a storm and we came with a helicopter to try and find a boat with migrants in distress. We located the boat, but before we could rescue the passengers, the boat sank. More than 200 people drowned in front of our eyes and we couldn't do anything. It was awful."

Despite the dangers, migrants seeking a better future and refugees fleeing war and persecution continue to board flimsy boats and set off across the Mediterranean and the Atlantic in a bid to reach European territories such as Lampedusa and Spain's Canary Islands. But some patterns are changing as governments react to this influx.

Information provided by Italy and Spain suggest that, for the first time in years, the number of boat people arriving on their shores from North Africa has decreased considerably. At the same time, in the eastern Mediterranean, the number of people crossing irregularly from Turkey into the Greek islands has increased dramatically.

Meanwhile, hundreds of migrants and refugees continue to drown or simply disappear while attempting the perilous crossings. "Rarely a week goes by without some news of an unseaworthy boat that has sunk with its passengers on board, dead bodies being washed ashore on the holiday beaches of southern Europe," said UNHCR's Assistant High Commissioner for Protection Erika Feller.

Smugglers use four main sea routes to bring people into Europe: West Africa to the Canaries; Morocco to Spain; Libya to Malta, Sicily and Lampedusa; and Turkey to Greek islands in the Aegean Sea. Less frequently-used sea routes run from Algeria to Sardinia and from the Black Sea coast of Turkey into Bulgaria and Romania.

Spain and Italy released figures in August which showed that arrivals since the start of the year had fallen substantially. In the Canary Islands, for example, some 7,000 people had arrived by sea, compared with almost 32,000 for the whole of last year.

In Italy, some 14,000 people have arrived this year, against some 22,000 for the whole of last year. Meanwhile, a total of 1,780 people arrived in Malta by boat in 2006, compared to about 1,500 so far this year. All these figures are not expected to rise much higher this year because the main summer sailing season is ending.

Spain's Ministry of Interior attributed the dramatic fall to stepped up patrolling and interception operations off the Canaries, better collaboration with the countries of departure, and information campaigns in the countries of origin, pointing out the risks of such voyages.

In contrast, the number of people arriving irregularly in Greece by sea from Turkey has increased dramatically this year. The average number of people arrested, intercepted or rescued by the Greek coastguard in the Aegean every year since 2002 has been around 3,000. But so far this year, police report close to 5,000 people arrested in the islands of Samos, Chios and Lesvos alone.

People risk their lives at sea for a variety of reasons. Some are seeking employment, many want to reunite with family members and still others are fleeing persecution, conflict or indiscriminate violence in their countries and have no choice but to head for safety along so-called mixed migration routes.

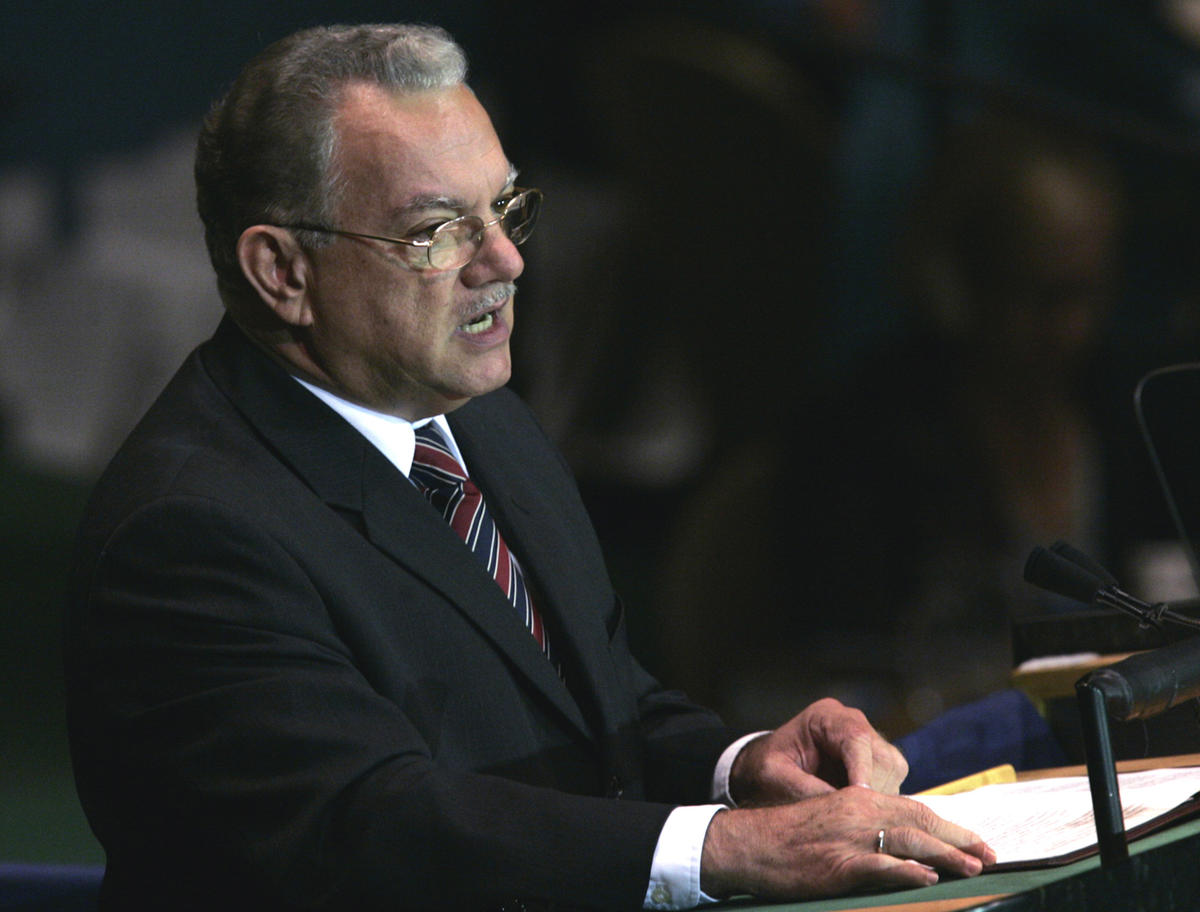

"In the Mediterranean, the Gulf of Aden and the Caribbean, along north-south frontiers and, increasingly, along south-south borders, in the midst of migrants in search of a better life there are people in need of protection - refugees and asylum seekers, women and children victims of trafficking," High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres told members of UNHCR's governing body earlier this week. "The ability to detect them, assure them of physical access to asylum procedures and a fair consideration of their claims, is a key element of our mission."

It is very difficult to know the exact percentage of those in need of protection. Official statistics in most countries, for example, do not include information on how an asylum applicant arrived - whether by sea, land or air.

The number of boat people applying for asylum varies widely. In Malta, roughly 70 percent of those arriving by sea apply for asylum and just under half of them are recognized to be in need of international protection. They receive either refugee status or another form of protection.

In the case of Italy, one third (6,000 people) of those arriving on Lampedusa last year applied for asylum. This amounted to roughly 60 percent of all asylum applications in Italy. On average, almost half of all asylum applicants in Italy are recognized as refugees or granted protection status. In contrast, only a small proportion of those arriving by boat in the Canaries - most of them from West Africa - apply for asylum.

Asylum seekers in Greece include an increasing number of Iraqis, as well as people from other countries in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa and South Asia. In the first six months of this year, some 3,500 Iraqis applied for asylum in Greece - the second highest number in any industrialized country, after Sweden. The figure, however, includes Iraqis arriving by land and air as well as by sea.

Those arriving by irregular routes in Greece face major difficulties getting access to asylum procedures. But a guide to asylum procedures, published by the Ministry of Public Order with UNHCR help, is expected to help improve the situation.

While the numbers of people crossing to Italy and Spain seem to be on the decline, humanitarian organizations fear that people smugglers are taking longer and more dangerous routes and using smaller boats to avoid detection and interception. But people are still willing to take the risk and hand over large amounts of money to people "whose last concern is the welfare of their clients," said UNHCR's Feller.

"Boats are totally unseaworthy and crammed with 40 or 50 people. The helm is often given to people with no knowledge of sailing or navigation," added Laura Boldrini, the refugee agency's Rome-based regional spokeswoman. "There are areas of the Mediterranean that are becoming a sort of Wild West where human life has no value at all," she added.

The exact death toll will probably never be known as some flimsy vessels disappear without trace. Based on media and police reports, however, UNHCR estimates that more than 500 people have died during crossings in the Mediterranean this year. Non-governmental organizations believe the figure could be closer to 1,000.

The UNHCR figures include 93 dead and 226 missing in the Sicilian Channel, and a further 150 dead trying to reach the Canary Islands or the Spanish mainland from North Africa. In Greece, official figures report 44 boat people drowned and 54 missing between January and late September in the Aegean. This compares to nine people reported dead and 10 missing last year and 10 dead with 16 missing in 2005.

Given the complexity of the issues involved, protecting the rights of asylum seekers and refugees in the context of irregular migration movements in the Mediterranean and other seas around the world is a major challenge and a high priority for UNHCR.

In order to help governments, UNHCR has begun implementing a 10-point plan which sets out key areas in which action is required to address these issues in countries of origin, transit and destination.

While recognizing that border controls are essential for combatting international crime, including smuggling and trafficking, the plan stresses the need for practical protection safeguards to ensure that such measures are not applied in an indiscriminate or disproportionate manner and do not lead to refugees being returned to countries where their life or liberty would be at risk.

The plan identifies the need for training and clear instructions for border guards and immigration officials on how to respond to asylum applications, and how to meet the needs of separated children, victims of trafficking and other groups with special needs. It also calls for appropriate reception arrangements to be set up to ensure that the basic human needs of people involved in mixed movements are met.

By William Spindler in Lampedusa, Italy