Central Asian states explore issue of statelessness at EU-UNHCR workshop

Central Asian states explore issue of statelessness at EU-UNHCR workshop

DUSHANBE, Tajikistan, April 26 (UNHCR) - The UN refugee agency has completed a two-day workshop on the prevention of statelessness in Central Asia, where the dissolution of the Soviet Union and civil conflict have left thousands of people without a determined nationality.

The workshop, held in the Tajik capital of Dushanbe on Tuesday and Wednesday under the European Union-funded project, "Institutional and Capacity Building Activities to Strengthen the Asylum System in Central Asia", gathered 33 government and non-governmental officials as well as UNHCR staff from Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

"This is an important event for the countries of the former Soviet Union and the region," said Gulchehra Sharipova, Tajikistan's First Deputy Minister of Justice who opened the workshop. "We have survived a period of transition and faced many new challenges, including statelessness. Tajikistan has seen its full impact; many people had to leave during the war [in the 1990s] and are still facing problems today. This meeting will open many doors and allow us to share experiences and exchange information on the issue."

International law defines a stateless person as someone who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law. According to official figures, there are at least 20,000 stateless people in Central Asia, including over 10,000 each in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, 194 in Tajikistan and an unknown number in Turkmenistan.

"These numbers are based on the number of people who have been issued stateless certificates by the authorities and do not represent the real scale of the problem," noted Philippe Leclerc, UNHCR's expert on the issue of statelessness, adding that one of the key difficulties is identifying stateless populations.

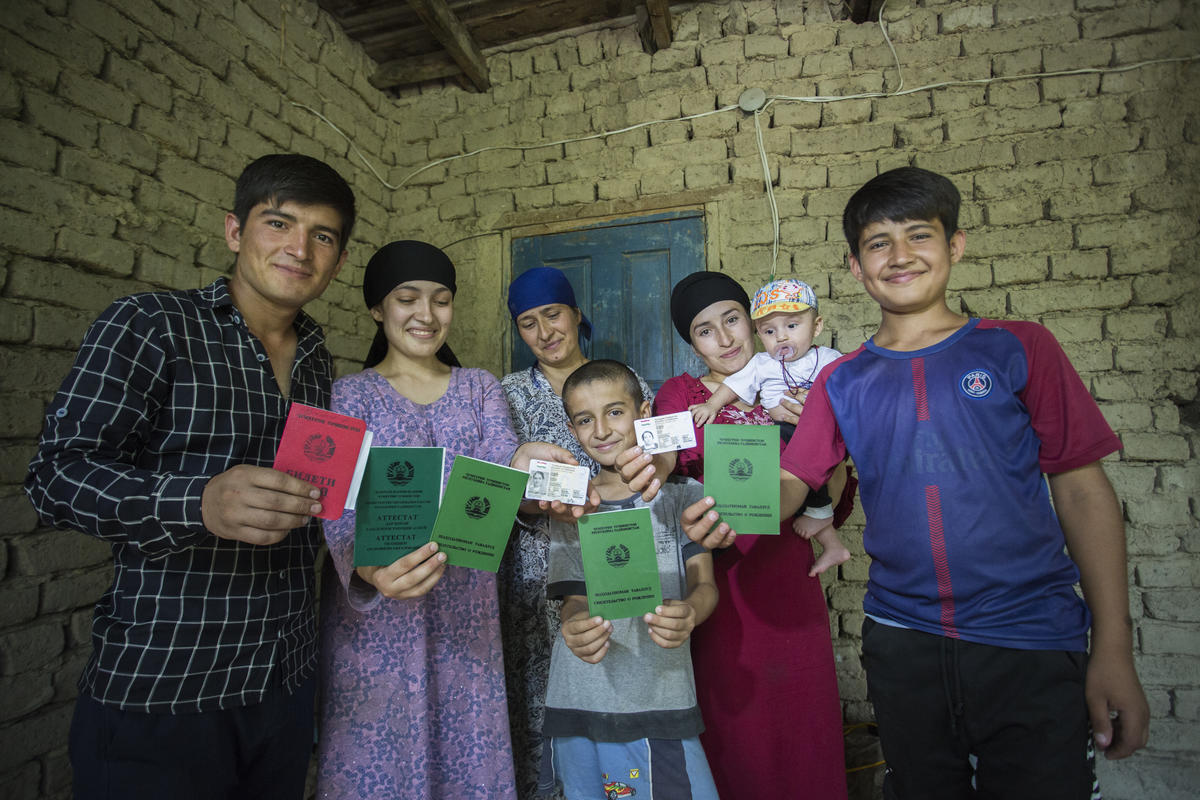

"Many people still live in the rural areas with old Soviet passports issued in 1974," he said. "They have not all replaced these old passports with documents issued by the newly independent states and only come to know of their problem when they try to travel, seek employment or enrol their children in school. They get into all kinds of Kafkaesque situations because they do not have a determined nationality."

The issue of statelessness is governed by the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. UNHCR was given this mandate in 1974 by the UN General Assembly. A total of 62 states are party to the 1954 Convention and 32 states to the 1961 Convention, none of them in Central Asia.

"UNHCR's job is to continually remind States of the huge scale of statelessness and to appeal to them to identify these people," said Leclerc. "Other sources of information include population census and birth registration."

A second element of the workshop focused on the prevention of statelessness. Leclerc told the participants, "You can do so by registering every child born on your territory, and by examining your nationality laws with a view to adopting and implementing safeguards to prevent the occurrence of statelessness resulting from reasons like the denial of women's ability to pass on nationality to their children, renunciation of nationality without having secured another one, and the automatic loss of nationality during long residence abroad."

The third element - reduction of statelessness - was best illustrated in the case of Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan, who resolved potential statelessness by naturalising over 20,000 Tajik refugees on their soil. Kazakhstan also referred to a high number of stateless persons being naturalised each year.

Most delegations also expressed interest in reducing statelessness by starting targeted information campaigns in areas with a high density of potential stateless people, to inform them of their rights and the relevant procedures to address their problem.

On the last element, the protection of stateless persons, the participants said their countries offered similar rights and benefits to stateless people with permanent residence permits as their own nationals. This includes the right to travel with documents issued by the authorities but excludes the right to take part in elections and the obligation to perform military service.

"The stability of a country depends on the stability of its population," said Mursalnabi Tuyakbayev from Kazakhstan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. "I'm happy we could come and learn from each other's experiences, and I hope we can continue this dialogue regularly."

Zumrat Solieva, who heads Tajikistan's Citizenship Unit at the Migration Service under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, added, "We are planning a new nationality law and will make sure what we discussed here is taken into consideration."

The Dushanbe workshop was the first in a series of regional workshops and seminars planned under the "Institutional and Capacity Building Activities to Strengthen the Asylum System in Central Asia" project, 80 percent of which is funded by the EU and 20 percent by UNHCR. The project is scheduled to end in December 2007.

By Vivian Tan in Dushanbe, Tajikistan