Cameroonian chief wins UNHCR Nansen Award for his village’s embrace of refugees

Cameroonian chief wins UNHCR Nansen Award for his village’s embrace of refugees

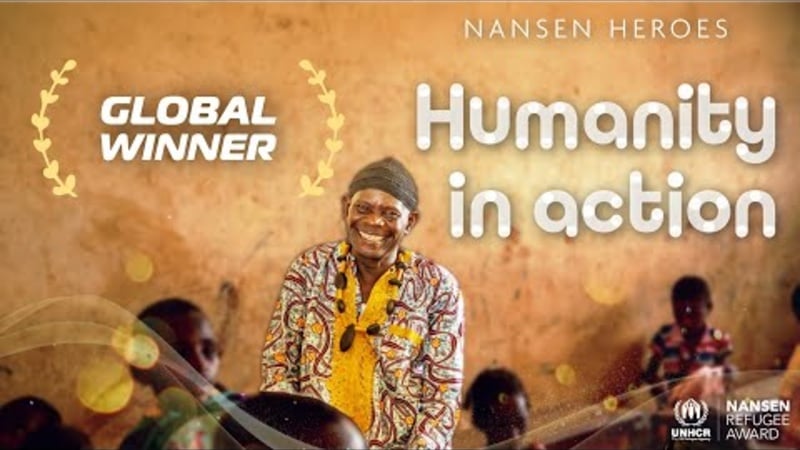

Martin Azia Sodea, the chief of Gado-Badzéré village in eastern Cameroon, is the 2025 UNHCR Nansen Refugee Award Global Laureate.

It takes more than 10 hours by road from Cameroon’s capital, Yaoundé, to reach the village of Gado-Badzéré in the country’s far east. At first glance, this rural community near the border with the Central African Republic (CAR) looks unremarkable, but amid the modest homes and red earth fields lies a truly remarkable spirit of hospitality that has transformed countless lives.

His Majesty Martin Azia Sodea, the current chief of Gado-Badzéré, was born in the house that still serves as the chief’s residence. The grand title belies the quiet authority and softly spoken nature of a man who is as comfortable working in the fields in rubber boots as he is presiding over meetings in his richly patterned ceremonial robes.

As a child, Chief Sodea watched his father settle disputes, welcome visitors and work hard to keep the village united. He remembers a home whose doors were always open, and where anyone who needed to could find a place at the meal table.

"Here, I was taught never to offend, never to refuse help. Our parents raised us with humility and openness. There was always food for everyone," Chief Sodea recalled.

After completing school, he joined the gendarmerie, where he served for 33 years before retiring. His career included training in crisis management and working as a UN peacekeeper in CAR – a role that deepened his understanding of conflict, forced displacement and the need to protect civilians.

In 2014, as armed conflict raged in CAR, thousands of refugees crossed the border seeking safety in neighbouring Cameroon. At the time, Gado-Badzéré had just over 12,000 residents, but the community did not hesitate to host up to 36,000 refugees. Eleven years later, the chief and the entire village agree that welcoming them was the right choice.

"The first refugees who arrived here were hungry after travelling long distances in harsh conditions. I can still remember the cries of the children and the exhausted mothers who could no longer carry their babies," the chief said.

Chief Sodea chairs a meeting of local and refugee residents of Gado-Badzéré village in eastern Cameroon.

For the chief, the elders and the whole community, the immediate priority was protecting lives. It was not about charity or obligation, but an overwhelming sense of moral duty and a way to honour their own traditions.

Hospitality extended far beyond setting up a site to host families and distributing shelter and food. In Gado-Badzéré, it meant full coexistence. "From the start, it was never an option to isolate the refugees," Chief Sodea explained. "We decided they should live among us, move freely in the village … and that we, too, could enter their site whenever we wished. No distinctions, no barriers."

In recognition of the profound solidarity shown to refugees by him and his community, Chief Martin Azia Sodea has been named the 2025 UNHCR Nansen Refugee Award Global Laureate. Presented annually, the prestigious award celebrates those who go above and beyond to help forcibly displaced or stateless people. Alongside this year's Global Laureate, four regional winners will also be honoured at a prize ceremony in Geneva on 16 December.

Education and health: symbols of welcome

The primary school where Chief Sodea studied is now one of the most visible symbols of refugee inclusion. Nearly 65 per cent of its students are refugees from CAR. In one first-grade classroom, 154 pupils share a space designed for a third of that number. Yet there is no distinction between local and refugee children – they learn, play and grow up together.

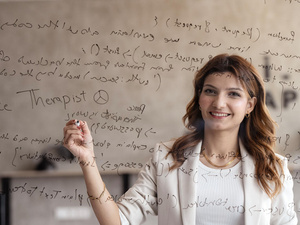

For Jacqueline Aissinga, a first-grade teacher at the school, educating these children is not just a job but a responsibility to the entire community. "It’s up to us to provide them with the foundation. When I enter the classroom, I know I’m building the future of the whole village," she explained.

Despite her overcrowded classroom and other challenges, her commitment to every child is unwavering: "I want to see these children grow up without weapons in their hands. I want them to succeed, to become leaders and responsible citizens."

Jacqueline Aissinga teaches a first-grade class of local and refugee pupils at Gado-Badzéré Primary School.

In the nearby school canteen, Nazira Pélaji, 52, a mother of seven, cooks alongside other women from the village. While eggs simmer in large pots on the fire, laughter fills the air as they prepare the pupils’ lunch, their movements synchronized and familiar. In the bustle of the kitchen, the distinction between refugees and locals evaporates like the water boiling in the pans.

Nazira arrived from Bangui in 2014 and vividly remembers her first moments in Gado-Badzéré: "When we arrived, we were tired and lost. But Cameroon welcomed us. The government and the chiefs gave us a place to sleep, food and care. I can never forget that," she said.

Eleven years later, her children have been raised here – some were born in the village. Six still attend the local school. Her only ambition, she says, is to give them a better future. As she works alongside the other women, her easy smile reflects a deeper truth – Gado-Badzéré is no longer simply a place of refuge; it has become home.

Canteen staff distribute lunch to pupils at Gado-Badzéré Primary School.

A few hundred meters from the chief’s palace, the local health centre treats a steady stream of patients daily. In the waiting room, conversations blend in Sango, French, and Gbaya – a reflection of the universal health coverage that benefits Cameroonians and refugees equally.

If Gado-Badzéré is a shining example of the welcome shown to refugees, it is part of a wider national commitment to refugee inclusion reflected in Cameroon’s pledges at the Global Refugee Forums in 2019 and 2023. This whole-of-government approach aims to expand refugee access to social services, enhance self-reliance and promote local integration, shifting from a humanitarian response to a long-term development agenda.

Growing self-reliance

Since the arrival of Central African refugees, Gado-Badzéré has received support such as food, shelter and sanitation services from UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, NGOs, and other international organizations. But over time, humanitarian aid has dwindled. Food distributions – once regular – have become sporadic and insufficient. As a result, the chief and other villagers had to find ways for the refugees to help themselves.

"Family dignity depends on their ability to feed themselves," said Chief Sodea. "When aid began to decline, we had to find a solution. I made land available for us to farm together. The crops – cassava leaves, tubers, maize – help entire families survive."

In total, about 66 hectares have been provided to the refugees for farming. As well as boosting their self-reliance by producing their own food and selling surplus on the local market to earn an income, the move has also strengthened social ties between refugees and hosts, fostering mutual support and exchange.

Chief Sodea (centre) helps clear weeds from a field set aside for refugees from the Central African Republic in Gado-Badzéré village, eastern Cameroon.

Chief Sodea says sharing land with the refugees was the right thing to do, providing long-term stability similar to including them in education and health care services. "Land doesn’t disappear. It’s been here since our ancestors and will remain after us. So why keep it for ourselves?" he said. "We know refugees won’t stay forever. So it’s better to let them farm, feed themselves and rebuild."

Peaceful conflict resolution is another cornerstone of Gado-Badzéré’s approach. To maintain cohesion, a weekly council brings together the chief, his elders, and refugee representatives. Together, they address tensions, identify potential sources of conflict, and look for immediate solutions to prevent escalation.

"We created mixed committees. Whenever there’s a problem, the sector chief comes to us, and we resolve it together. Since refugees arrived in 2014, we’ve never needed to go to court," the chief explained.

Bittersweet goodbyes

When some Central African refugees choose to return home, taking advantage of the gradual improvement in security in their country, the chief admits it can be a bittersweet moment.

“It hurts us. Every time, it’s a real heartbreak to see people leave who have been an integral part of our community for more than a decade,” he said.

But as long as their returns are voluntary and safe, he understands the draw of home. “They have already suffered. I hope they return to real peace, so they never experience atrocities again,” he added.

Chief Martin Azia Sodea embraces a refugee resident of Gado-Badzéré village in eastern Cameroon.

For those that remain, Chief Sodea said he is happy to see the invisible line between “them” and “us” gradually disappear. “Today, our children speak Sango and Gbaya. We live together,” he said, referring to the two main languages spoken by the refugees from CAR and their Cameroonian hosts respectively.

Despite the key role his leadership and example have played in Gado-Badzéré’s welcome and hosting of tens of thousands of refugees, Chief Sodea’s chief pride is how the whole community stepped up and showed what can be achieved with open minds and hearts.

“It's a source of great pride that Gado-Badzéré is now known worldwide. Gado represents Africa, represents Cameroon,” he concluded. “[Receiving refugees] was not easy. It wasn’t something everyone was expected to do. But we had the heart for it, and I thank the people of Gado again for accepting this.”