Help us revive our traditional lands, ask Afghan Kuchi returnees

Help us revive our traditional lands, ask Afghan Kuchi returnees

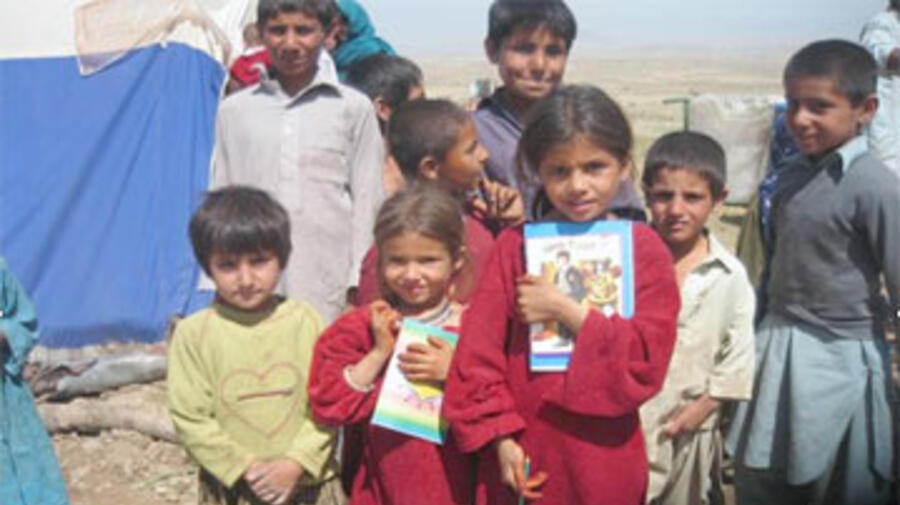

Kuchi returnee children find limited schooling at Bot Khak.

BOT KHAK, Afghanistan, December 24 (UNHCR) - As nomadic animal herders, the Kuchis have a good eye for land, honed from centuries of moving in search of greener pastures. So when thousands uprooted themselves from Pakistan and returned home to Afghanistan, one imagines they headed for nothing less than the Garden of Eden. What they found was an arid dustbowl mired in dispute and scattered with explosives.

The saga started in spring this year, when Afghan Kuchi elders of the Ahmadzai tribe got together from all over Pakistan to discuss their situation. "One of the main problems in Pakistan was the closure of camps like Kacha Gari. The elders talked and decided that we should all come back, before others occupy our land in Afghanistan," said Aziz Khan, one of the Kuchi representatives. Another fear was that since many did not have legal status in Pakistan, they could be detained and deported under Pakistan's Foreigners Act.

As a result, some 1,000 Kuchi families from camps and towns throughout Pakistan packed their bags and left in one of the largest spontaneous return movements of the year. Hundreds of trucks were hired to move extended families, belongings and livestock back to their pastoral homeland in Bot Khak, some 25 km outside the Afghan capital Kabul.

The logistically challenging operation was organized by the returnees themselves as most did not have Proof of Registration (PoR) cards from a recent Pakistan government registration exercise and thus did not qualify for repatriation assistance. They said they had not applied for PoR cards mainly because it was culturally unacceptable for their women to be photographed. Even those among the group with PoR cards chose to forgo the $100 repatriation grant in favour of returning en masse as a tribal group.

The community said an additional 1,000 families have since joined them, bringing the total population at Bot Khak to over 2,000 families. However, they had no legal claim to the land as it had been allocated to other groups in their absence. As the land dispute dragged on, Afghanistan's Emergency Commission advised the humanitarian community to provide only temporary emergency aid, not permanent structures such as wells and houses.

UNHCR distributed emergency supplies and other assistance, and led the advocacy effort from the moment the tribe arrived, taking along various agencies to meet them. This led to de-mining by the UN Mine Action Centre for Afghanistan, the provision of educational supplies by UNICEF and temporary water tankers by the Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation and the Afghan Red Crescent Society. Although the returnees were not allowed to build anything permanent until the land dispute was resolved, those who could afford to went ahead with constructing houses and wells.

"There is no potable water here, we have to walk one or two hours to the spring for water," said Khan. "We do daily-wage jobs if we can find any in Kabul city, but half the money goes to transport. We've lost most of our livestock and become settled during the years in Pakistan. We can settle here too, but we need more assistance."

However, during a recent visit to the site, UNHCR discovered that only 200 families were left. In true Kuchi tradition, the large majority of Bot Khak's population had escaped severe winter and moved to warmer locations in Nangarhar and Laghman provinces until the onset of spring. Others are believed to have returned to Pakistan to find jobs as they could not find employment in Afghanistan. The community said that with shelter and livelihood assistance, they would be able to lead the settled lifestyle they had enjoyed in Pakistan.

The remaining 200 families cannot afford to move and are sharing tents and half-built homes at Bot Khak. "Winter is coming and we have no firewood," said Khan. "I am afraid that in the poorer families, some of the children may die from the cold."

UNHCR has assisted the most vulnerable families with cash grants and is working with government partners and aid agencies to find winterization materials for these families.

Longer-term needs include education for the boys and girls at Bot Khak. "Next to survival needs - water and shelter - education for our children is the most important priority for us," they said. UNHCR provided tents for a community-based school with temporary lessons for the children. But limited resources meant that students from Class One to Six sat in the same lesson, making it impossible to cater to each level's needs. With no government salary support, the teacher could not continue working.

"The children are upset with the lack of schooling here. The facilities in Pakistan are much better. We've sent many of them back to Peshawar and Islamabad to continue their studies," said Khan.

Summing up the challenges, UNHCR's Head of Sub Office Kabul, Maya Ameratunga, said: "The repatriation of this tribe illustrates the difficulties of return under pressure in scenarios like camp closure, to problematic situations such as land disputes. Unfortunately, the lack of reintegration prospects such as education and jobs leads to reverse movements back to Pakistan. This community has shown commendable self-help and our hope is that, once the land dispute is properly resolved, they can be supported to make their repatriation sustainable."

Recently, the community received a Presidential Order confirming their rightful ownership of the Bot Khak site. Ultimately, it's clear where home is, even for traditional nomads like the Kuchis. "With these hands we will rebuild Afghanistan, men and women together," said Khan.

By Vivian Tan in Bot Khak, Afghanistan