Canadian programme gives hope to Afghan refugees in Central Asia

Canadian programme gives hope to Afghan refugees in Central Asia

Afghan poet Mohammad Haroon Rahoon, who fled his war-torn homeland in 1993, left for resettlement in the Canadian city of Toronto last month.

ALMATY/DUSHANBE, June 14 (UNHCR) - They both came from Kabul and are heading the same way - to Canada - but Mohammad Haroon Rahoon and Saliha Azizullah have taken very different routes along the way. He fled one conflict for another, while she has known nothing but heartbreak in exile.

Both are among more than 2,700 Afghan refugees in Central Asia who have been given a new lease on life through the Canadian accelerated resettlement programme in the last two years. Since the first group left Kyrgyzstan in 2004, many more have followed from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan in a continuing process to resettle the most vulnerable refugees who can neither repatriate nor integrate in their host country.

"After the Najibullah government collapsed [in Afghanistan in 1992], the mujahideen came from the mountains with their long beards and robes. The new regime was hard for people who lived in the city and were free. As a journalist, I wrote poems and articles about the relationship between people and God. I feared for my life," said 34-year-old Haroon.

In 1993, he left his native Kabul, travelled north to Mazar-i-Sharif and crossed the Pyanj river into Tajikistan, where he joined his father and sister in the capital, Dushanbe. Tajikistan was in the middle of a civil war. "There were problems, but not as bad as in Afghanistan," said Haroon. "UNHCR registered me and gave me a refugee card, which kept me out of trouble."

The UN refugee agency provided financial assistance until the Afghan refugees organised a market among themselves. Haroon commuted between Dushanbe and Moscow, selling clothes and toys. But he never forgot his first love - poetry - and set up an association of Afghan poets, creating publications and writing numerous books about his homeland. His poems have been used in songs by Afghan and Tajik singers.

"During the Nauroz [Persian New Year] celebrations, the Tajik president said all poets should learn to write like me," he said with pride.

For fellow Afghan refugee Saliha, culture and education are a luxury when she can barely afford to feed her children in the Kazakh capital, Almaty. The family left Kabul in 1992 after repeated attacks by ex-convicts from a prison her husband had worked in. The gangs followed them to Pakistan, forcing them to flee to Almaty, where they have relatives.

Soon after, Saliha's husband killed himself and left her with four children aged three to 13. With help from UNHCR and the Public Fund for Support of Afghan Diaspora, they were recognised as refugees in Kazakhstan. The Public Fund - a local non-governmental organisation - pays their rent while another UNHCR partner, the Red Crescent Society, gives them 11,000 tenge (US$85) in allowances every month.

"I do domestic work for some families and get food in return. We live in one room and sleep all over, like animals in a pen," she said with a resigned smile.

The 37-year-old widow has no time or money to take her children to school. "My eldest daughter is too old to start Grade One. And at 10,000 tenge per month, kindergarten is a dream for my younger children. So they all stay home," she said as her hyperactive twin boys wreaked havoc in the tiny apartment.

But no matter how hard life is in exile, Saliha will never go back to Kabul. "I love my country, but I can't forget the trauma. I don't see a life for my family there."

Thankfully, there is another option for vulnerable cases like hers - resettlement to a third country. Out of the 2,720 Afghans accepted for resettlement under the Canadian programme in Central Asia, 2,205 have left for the North American nation in the last two years.

Saliha and her children have gone through the requisite interviews and medical checks, and are now waiting for a visa to Canada. "I don't know anything about Canada, but during the [resettlement] interview they told me my children will go to school and I can pay rent from my salary," she said. "I know I'll live a peaceful life and the children will succeed and prosper there."

Poet Haroon was equally hopeful before he left Dushanbe for Toronto with his journalist wife and aunt recently. "Of course I'll miss Tajikistan. It's my second homeland. I live breathing its air."

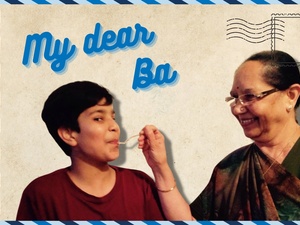

Afghan widow Saliha Azizullah and her children are waiting for resettlement to Canada from their one-room flat in the Kazakhstan capital, Almaty.

But he has not forgotten about his motherland: "I've asked my friend to bring me a handful of sand from Afghanistan. Too many people died there, their blood is all over the land." He also packed an archive of his works. "Once I'm in Canada, I want to introduce Afghan and Tajik artists to the world."

Asked if she can cope with the new life ahead, Saliha said, "When life is stressful, I can even forget my own culture. But if there is peace and stability, I can learn a new culture and the skills to survive."

By Vivian Tan in Dushanbe and Almaty