Refugees Magazine Issue 128 (Somali Bantu) - Editorial: A lucky few

Refugees Magazine Issue 128 (Somali Bantu) - Editorial: A lucky few

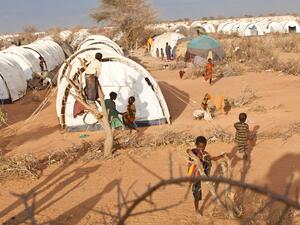

When the nation-state of Somalia collapsed into a series of warring fiefdoms in the early 1990s, hundreds of thousands of civilians fled for their lives. Some have since returned home, but many are still refugees, principally in neighbouring Kenya, with little idea of when, if ever, it will be safe for them to return home.

A lucky few, however, will soon be starting an unbelievable journey, swapping a lifetime of poverty and semi-slavery and years of exile in a refugee camp for a new and totally different life in the United States.

For a decade the U.N. refugee agency tried to find a new country for approximately 12,000 so-called Somali Bantu, a group whose ancestors were seized by Arab slavers from their ancestral homelands, who continued to be widely discriminated against and victimized in their 'new' home in Somalia prior to the war and who vowed they would not return to that country even if peace is restored.

After two early attempts to relocate the Somali Bantu failed, Washington has now agreed to take the bulk of the group - subject to final vetting which is currently underway.

Seventeen countries annually accept for permanent resettlement around 100,000 particularly vulnerable people from among the 12 million refugees UNHCR cares for, but who, for various reasons, cannot go home whatever the state of their country.

Traditional 'hosts' such as the United States, Canada, Australia and the Scandinavian countries accept the bulk of the resettlement cases, but increasingly states as diverse as Iceland, Brazil and Benin have also participated.

Resettlement can be both highly prized and highly politicized. At the height of the Cold War, for instance, refugees fleeing the Soviet bloc were openly welcomed in the West which also underwrote a worldwide programme to resettle Indochinese refugees in the wake of the Viet Nam war.

Encouragingly, resettlement countries recently became more flexible in responding to the needs of less high profile groups, especially from Africa.

But these resettlement programmes, no matter how welcome, cannot accommodate every deserving case. In Kenya's Dadaab and Kakuma camps, Somali refugees who fled the same conflict as the Bantu have watched the resettlement process with both anguish and anger, a single question burned into their faces: "Why can't we go too?"

The Bantu now face a frightening cultural chasm. Most cannot read, write or speak English. They are sturdy farmworkers with few other skills, who have never turned on an electric light switch, used a flush toilet, crossed a busy street, ridden in a car or on an elevator, seen snow or experienced air conditioning.

But as one said in the following report on the Bantu, their history, years in exile, and now this incredible new adventure, the choice between America and Somalia is "between the fire and paradise."

Source: Refugees Magazine Issue 128: "America here we come" (September 2002).