Mayor of Hungarian border town gears up to welcome Ukrainian refugees

Mayor of Hungarian border town gears up to welcome Ukrainian refugees

Nowadays, Helmeczi’s phone rings every couple of minutes. Many of the calls concern Ukrainian refugees.

“This one is important,” he says, glancing at his phone before answering. The call is about a couple in their sixties who recently fled their home in southern Ukraine’s Kherson Oblast province and are living in a crowded 20-bed dormitory in a temporary shelter in Záhony.

There is good news: the local council has found a vacant house for the couple. It just needs a good clean to be made ready for them. The mayor only needs to give the go ahead.

The six months since the start of the war in Ukraine and the refugee crisis it triggered, have been a non-stop whirlwind of quick-thinking and problem-solving for Záhony and its mayor. “We haven’t had the opportunity to step back and thoroughly reflect on what we’ve been going through yet,” Helmeczi says.

The struggle today is maintaining the humanitarian response as enthusiasm fades and donations dry up after the early outpourings of support. As the first weeks of the emergency turn into months of displacement, the need for assistance has remained vast. UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and partners provide Ukrainian refugees with immediate help upon their arrival in Záhony, such as information, hot food, and medical care. The government-led response—in close cooperation with UNHCR and the municipality—then takes over, providing shelter, transport, and other continuing support.

“From coordination to connections and to putting in extra work hours, municipality workers play an essential role in making all this happen,” says the mayor. “And in the meantime, we’re also running a town.”

Arrival numbers in the past months may have fallen, but longer-term solutions are in high demand. Beyond the search for an overnight shelter, Ukraine’s refugees now need jobs, childcare, and affordable accommodation.

Záhony is the only border town between Ukraine and Hungary with a railway station, and this legacy of the Soviet-era past—dating back to when the state-run railway company employed 8,000 people here in the 1980s—has made it an unexpected magnet in the present. At the beginning of the year, more than half of the town’s 4,500 residents were retired, and there were barely any school-aged children. Then, Helmeczi’s job reflected the interests of his aging constituents. “The priorities of our citizens were clear,” the mayor says. “We had to keep the streets silent, and the cemeteries tidy.”

Everything changed on 24 February, 2022. Helmeczi began his working day as he always did, by catching up on the news. He was shocked to learn a war had started in neighbouring Ukraine, but he did not immediately realize it would mean the end of his job as he knew it.

"I put out a Facebook post on what we needed at 1 p.m., and by 6 p.m. a nearby shelter was ready."

Luckily, Helmeczi is a man of swift decisions. “It was late February, with freezing temperatures. We couldn’t expect people to spend the night at the railway station! I put out a Facebook post on what we needed at 1 p.m., and by 6 p.m. a nearby shelter was ready to host refugees,” he says.

Soon after the first refugees arrived, donations started pouring in. Then volunteers. Then came the authorities, NGOs, and aid organizations. Life in the once quiet town was completely upended.

The mayor had not expected to become a key player in Europe’s fastest-escalating refugee crisis since World War II, but he rose to the challenge. “At first, we were so caught up in the issues at hand that we didn’t really realize the amount of human suffering we were dealing with. Only after a few weeks did we have the time to actually sit down and talk to people,” he says.

On a public holiday in July, the town council members gathered for an informal garden party. “If only for a few hours we had to be off-duty and take care of ourselves,” says Helmeczi. “We talked, laughed, tried to ease tensions. When the party was over, it was straight back to work.”

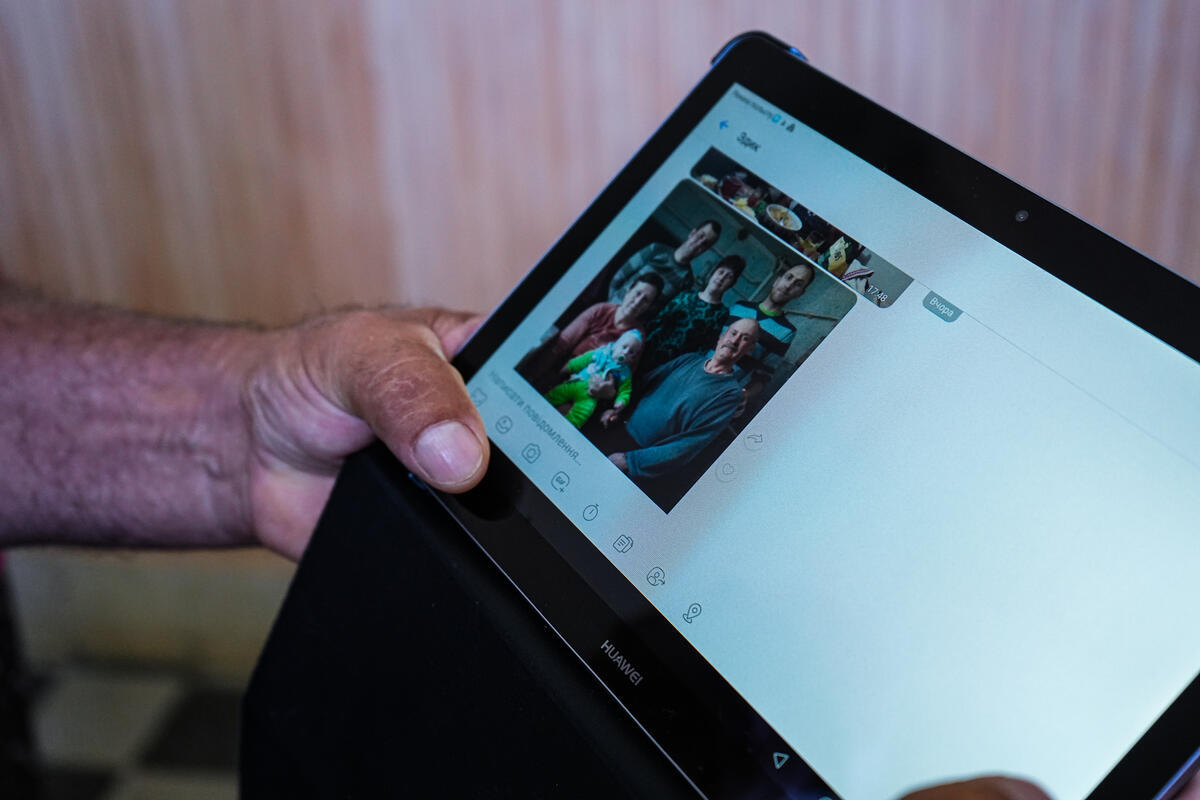

The case of the couple from Kherson Oblast living in the shelter is typical of Helmeczi's new responsibilities. Géza Vinda and his wife had a house and farm and were reasonably well-off. Now, they have nothing but the few possessions they could flee with, among them a handful of family photos.

At first, they thought they could withstand the war by sheltering in their basement, but as the months went by the situation only became more dangerous.

“We were the last ones on our street to stick around,” says Vinda. “But when the roof of our neighbour’s house was blown off while we were out of the basement feeding the animals, we decided it was time to leave.” He and his wife fled through the reeds of the nearby river as gunshots rang out behind them and eventually made it to the safety of Záhony, and the shelter of the dormitory.

When Helmeczi delivers the news to the couple that a home has been found for them, Géza becomes visibly emotional. Then, he pulls himself together, determined, like the mayor, to play his part. “Let’s go, we’ll clean that house ourselves,” Géza says. ”We’re not here to just sit around and wait.”