West African countries meet to discuss contingency plans for Côte d'Ivoire

West African countries meet to discuss contingency plans for Côte d'Ivoire

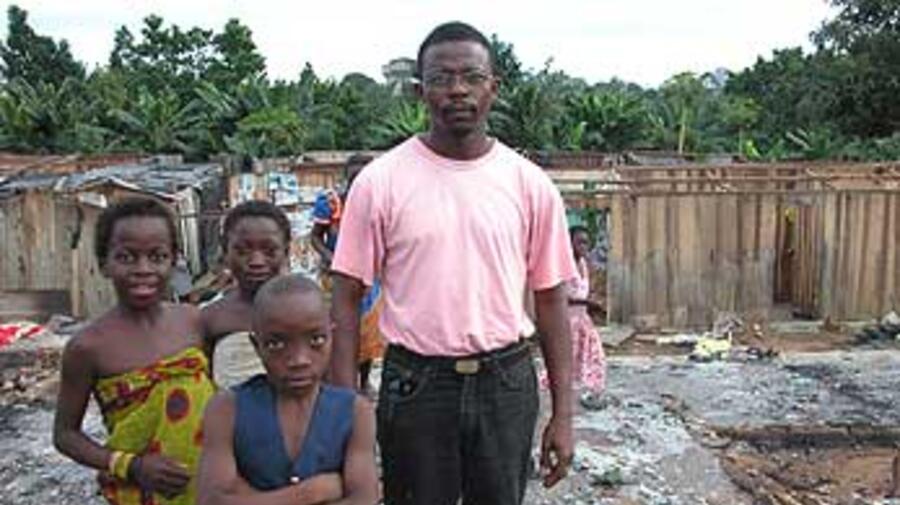

Liberian refugee Daude surveys the wreckage of his former home in Abidjan's Deux Plateaux area. He is just one of over 200,000 people displaced in Côte d'Ivoire.

ABIDJAN, Côte d'Ivoire, October 17 (UNHCR) - Representatives from West African countries are meeting in Ghana today and tomorrow to make contingency plans as the unstable situation in Côte d'Ivoire threatens to drive more refugees into the region.

The two-day meeting, which started Thursday in Accra, Ghana, gathered Côte d'Ivoire's neighbouring countries and various international agencies, including UNHCR, to address concerns that the Ivorian civil conflict may spill into the region.

Hundreds of thousands of people - Ivorians, immigrants and refugees - have been displaced in the wake of an attempted coup in Côte d'Ivoire on September 19. Some have crossed the borders, including nationals of neighbouring countries like Mali, Burkina Faso and Guinea who have been returning home amid rising xenophobia in Côte d'Ivoire.

Within the country, thousands of people continue to be displaced daily. More than 200,000 have been driven out of their homes in the central city of Bouaké, along with several thousand more in the southern commercial city of Abidjan. People are leaving en masse out of a combination of fear, hunger and poverty.

"If this crisis continues, the humanitarian suffering and consequences will be enormous," said Abou Moussa, UNHCR's Regional Co-ordinator for West Africa. "We can only hope a political solution can be found. After all, making political concessions will always cost less than making a war, a consideration that is valid for all belligerent parties."

Continued fighting has increased the fear among the local population and heightened ethnic tensions that were not obvious previously.

"I am convinced I will be going back to Bouaké," said Drocella, a Rwandan refugee. "There, I am part of the local community, we never had any problems. I felt like I was one with them. Now I can only hope I will be going back soon."

This is the third time Drocella is fleeing for her life. In 1994, she fled Rwanda for the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Two years later, she moved on to Côte d'Ivoire, where she settled in Bouaké. In 1997, she started working at a tertiary technical school there, where she is now the deputy director.

"Things are bad now, but I pray every day they'll get better," she said. Drocella is one of the 200,000 displaced people from Bouaké, where the humanitarian situation has deteriorated since she was evacuated in early October. A UN interagency mission visited the area between October 11-14.

"Bouaké is a ghost town," said UNHCR protection officer Thomas Scrive, who was part of the recent mission. "There are enormous needs for those who remain. People are hungry and products are scarce and expensive. Ethnic tensions have increased too."

As a result, thousands are leaving the town on a daily basis, walking for days until they reach a friendly home. Catholic missions on the roads out of Bouaké and in neighbouring villages have provided massive support for the exhausted passers-by. People stay for one to two nights to regain strength and energy, having a meal before travelling to other towns on local transport at highly inflated prices. Many head towards Abidjan, where people still feel safer.

But security is precarious even in the southern city. "Now I am afraid here too," said Dauda, a Liberian computer engineer in Abidjan who was chased out of his shantytown home on the night of September 19. "Ever since some of the locals started pointing fingers at us in those early hours of September 20, I knew it was time to leave."

On the night of the attempted coup, Dauda saw the police destroying his home in Agban district, Deux-Plateaux. After bringing his family to safety, he returned a little later to ask the police if he could go back for his ID card. He was allowed to run in for a few minutes, during which he managed to grab his card and a mattress.

"That is all I have with me now," said Dauda, who found accommodation three days later in a UNHCR-sponsored factory site in Koumassi district.

Three weeks later, Dauda ventured back to his home for a look. Bulldozers were destroying the sites, which government troops had burnt earlier in an attempt to root out rebels and ammunition. His direct neighbour, an Ivorian, ran up to him, embraced him and told him he had lost his home as well.

"My life was very fine before September 19. I had friends, a good job and my family was taken care of," said Dauda. "Sometimes I was bothered when people found out I was a refugee. They would ask me, 'Why don't you live near the border area?' and 'Why don't you have a normal ID card?' But I never really had a problem. I just replied that we, as refugees, were welcome in Côte d'Ivoire and that meant we were welcome everywhere in the country. At least that is what I believed."

The clearing of the shantytowns has slowed but is continuing in Abidjan, creating additional displacement by the day and putting pressure on the population. Abidjan's shantytowns house over 1 million people.

"We are trying to find long-term solutions for the displaced refugees - when and if the security situation calms down. But a lack of funds limits us in finding proper solutions for the unfortunate," said UNHCR programme officer Margarida Fawke. "The urban caseload has always been particularly under-funded, and with more people in need, this will only be a greater concern to us."