A bumpy road to belonging: Ibrahim’s struggle for citizenship

A bumpy road to belonging: Ibrahim’s struggle for citizenship

In Denmark, Ibrahim lives with his family in Brønderslev, where he remains stateless.

In and around the quiet town of Brønderslev in northern Denmark, Ibrahim Sultan spends his days behind the wheel of his taxi, picking up passengers. As a taxi driver, he’s used to answering questions from curious customers about his background and what brought him to Denmark. But when he reveals that he has lived in Denmark for over 20 years as stateless, the reaction is often one of surprise and disbelief.

“Many people don’t know what it means to be stateless or that stateless people exist in Denmark,” he shares.

There are currently more than 8,500 stateless people in Denmark. Being stateless means having no nationality and not being recognized as a citizen by any country. As a result, stateless people often face difficulties accessing basic rights.

“For me, being stateless means a profound sense of worthlessness, as it means lacking a connection to any nation,” Ibrahim explains.

A new beginning

Ibrahim is from the Rohingya community – the largest stateless population in the world. Throughout his childhood and youth in Myanmar, he endured bullying, abuse, and exclusion due to his ethnicity. Because Myanmar does not recognize the Rohingya’s citizenship rights, Ibrahim was born stateless and denied access to basic rights. Even moving around within his country of birth was a challenge due to the lack of documents.

At the age of 18, he fled to Malaysia in search of a better future. Here, he met his future wife, and the pair welcomed their first two children. After more than 13 years in the country, the young family was resettled to Denmark through UNHCR’s resettlement programme.

“I came to Denmark and got an opportunity to work. Here, my children have an opportunity to get an education and access to healthcare. I truly appreciate these opportunities that Denmark offers.”

Barriers to citizenship

When Ibrahim, his wife, and their two young children arrived in Denmark, they were granted temporary residence permits. This gave the parents the opportunity to work and allowed the children to attend kindergarten and, later, school.

For me, being stateless means a profound sense of worthlessness

Over time, the family grew. Ibrahim and his wife welcomed three more children – each born in Denmark and granted Danish citizenship. For Ibrahim and his wife, the greatest barrier to acquiring Danish citizenship is passing the required language and citizenship tests due to illiteracy.

“Those who haven’t gone to school in Denmark or learned to read and write find it very difficult to pass the test. That includes myself, my wife, and my mother-in-law. My wife, for example, never learned to read and write because she couldn’t go to school due to war. So it’s not easy for her to learn it now,” the 51-year-old explains.

Ibrahim comes from the Rohingya community, which represents the largest stateless group globally.

Ibrahim and his wife are far from alone in their struggle. Many stateless people face similar challenges. That’s why UNHCR has recommended that Denmark ease the path to citizenship for stateless individuals who are illiterate or otherwise vulnerable.

“UNHCR recommends exempting vulnerable persons, such as the elderly, and illiterate persons from language and knowledge requirements to help them have a fair chance,” says Rania Elgindy, Associate Legal Officer at UNHCR’s Nordic and Baltic office.

Travel complications

Because of their stateless status, Ibrahim and his wife cannot vote and do not hold passports. When traveling abroad, they must rely on temporary travel documents issued by the Danish Immigration Service. These documents often raise suspicion and lead to delays, questions, and complications when applying for visas or at the airport.

I now have my own business, and I don’t lack anything – except for citizenship

According to Rania Elgindy, many stateless people find themselves in similar situations.

“Stateless people often face significant barriers to international travel due to the complete absence of recognized travel documents. Even when documents are issued, they may not be accepted by other states.”

Ibrahim hopes to one day acquire Danish citizenship.

Holding on to hope

Today, Ibrahim runs his own taxi company and is an active member of the Rohingya community in Denmark, where he regularly meets with others facing similar challenges. And although the road to citizenship seems long and often out of reach, Ibrahim has not given up hope.

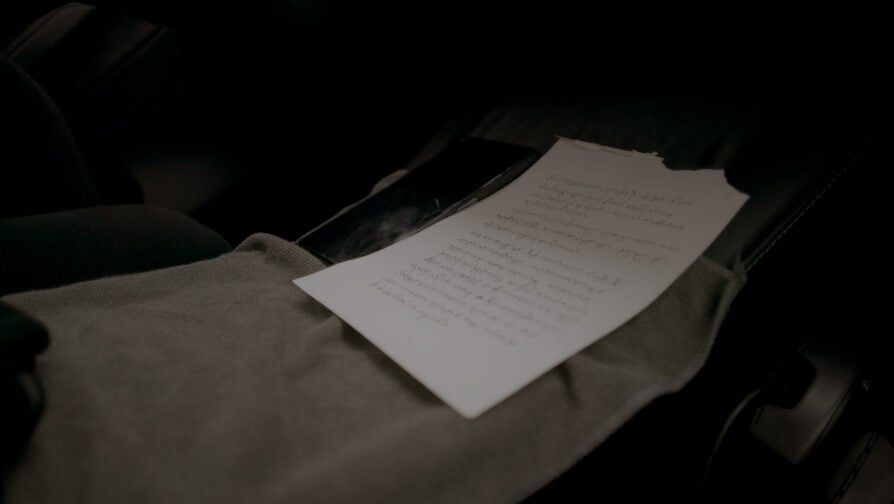

“I’ve been given a new life in Denmark and have always been grateful for the help I received when I arrived here without a penny to my name. I now have my own business, and I don’t lack anything – except for citizenship.”