The long road home to South Sudan after a lifetime in exile

The long road home to South Sudan after a lifetime in exile

A recently returned family living temporarily in Bor, South Sudan. Their home village, 75 km to the north, has no services whatsoever.

BOR, Sudan, November 29 (UNHCR) - Malak was just 10 when he fled war in his home village in South Sudan. Even now, 19 years later, he still remembers the scene vividly: "You could hear bullets flying around everywhere."

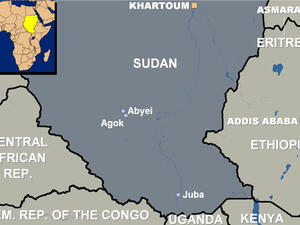

After years of walking across huge swathes of Africa, and more years living in exile as a refugee, Malak - now a 29-year-old father of three - has come back to Bor, in south-eastern Sudan, 16 kilometres from his home village.

It is a vote of confidence in what the locals call 'New Sudan,' and the result of a plan he first conceived in January this year, when a peace accord was signed putting an end to 21 years of civil war that displaced four million people to other parts of Sudan, and caused a further half million to become refugees in neighbouring countries.

"When the peace agreement was signed on January 9 this year, it was the beginning of the end [of the war]. We waited a bit to see if it was secure to come back," he says. "Now has come the time."

Without waiting for the UN refugee agency's help, he brought his family home to Bor. Thousands of other refugees are waiting for the official start of the UNHCR voluntary repatriation operation from neighbouring countries which is scheduled to begin before the end of the year, providing the security situation stabilizes in South Sudan. Many other southerners who have been displaced in camps in Khartoum are spending three weeks or a month travelling from the Sudanese capital to Bor by river barge.

Malak's entire life is a reflection of the violence and upheavals experienced by millions of refugees around the world. Malak recalls fleeing with his parents in 1986, when fighting between the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) and Sudanese government forces spread to their village: "We escaped the village and, with a group of other neighbours, we walked to Pochalla, at the border with Ethiopia. Sixteen thousand of us, from villages around Bor, arrived in Pochalla in the course of several days."

The group remained in Pochalla for two months, surviving thanks to the generosity of the local inhabitants, before moving to Panyudu, a refugee camp run by UNHCR in neighbouring Ethiopia. Five years later, in May 1991, the camp was attacked by rebels following the overthrow of the Mengistu regime in Ethiopia. "Many refugees were killed during the attacks," says Malak. "Some drowned trying to swim through the river back to Sudan."

Malak fled back to Pochalla, which was then an SPLA stronghold. When the Sudanese army attacked the town six months later, Malak and many others had to flee yet again, this time to Kapoeta, on the Kenyan border. Malak had to move several times along the border, as, one by one, towns under SPLA control were recaptured by the government. He ended up in Lokichoggio, in northern Kenya, in 1992, but even there his troubles were not over, as the refugees were victims of repeated attacks, this time by local tribes who stole their cattle.

Finally, UNHCR moved the group of refugees to Kakuma camp, further south in Kenya. There Malak grew up, received an education, got married and had three children.

His recent journey home from Kakuma was nearly as roundabout as his original flight into exile. Because the roads in the south of Sudan are still heavily mined, Malak and his family had to make a long detour via Kampala, the Ugandan capital, to Juba, the new capital of the south Sudan government. In Juba, the family boarded a speedboat and finally reached Bor after a one-day journey on the White Nile. The total cost of road and river transport? $220 per person for six days of travel - a small fortune in this part of Africa.

"It has been a very long journey since I left Bor almost twenty years ago," says Malak. "But now I am back to my land to rebuild South Sudan, to help my people."

In addition to completing his secondary education in Kakuma Camp, Malak received a scholarship to enrol in a one-year programme in computer science in Nairobi, and now hopes to pass his knowledge on to returnee children.

Because of the importance of education to the Sudanese, many returnees prefer to remain in Bor rather than go all the way to their village of origin, where there are absolutely no services.

"Some, especially the youth, will never go back to these villages," says Philip Thon Leek, the governor of Jongley State, where Bor is located. "They had access to health services and education in the [refugee] camps. The villages can not offer them these things at this stage. They will remain in town."

In Bor, pupils can attend day classes in Arabic and evening classes in English. But the few school buildings are in very bad condition, with severely cracked walls, and some classes take place either under the trees or in fragile makeshift shelters where the heat becomes unbearable during the day.

The population of Bor has mushroomed to 15,000, half of them refugees or displaced people who have returned in the last four months. In Bor and other areas, one of the major tasks for the international agencies will be to help establish some basic infrastructure and a minimum of services - which either never existed or were destroyed in the war.

"People drink the water from the Nile as there is absolutely no well, nor borehole, in town, and no way to treat the water," explains Claas Morlang, head of the recently opened UNHCR office in Bor. "We are certainly working on trying to change this situation and fund some safe-water projects very quickly." Diarrhoea and parasites are common because of the use of untreated river water.

Medical care is another huge need. "This is just a skeleton of a hospital here, there is absolutely nothing in it," says Dr. Benjamin Malek Alier, who is originally from Bor and has returned to help for a few months, after more than two decades in exile. "No water, no electricity, no drugs, no nothing.... If we have to do a major surgery or a blood transfusion, it is just impossible - we don't have the capacity at this point."

Despite the difficulties, returnees like Malak face the future with remarkable confidence, and are eager to rebuild their homeland. "I could get a better life outside of South Sudan at this stage," says Malak. "But I really made the decision to come back because we are citizens of this land. We were born here. This is our land."

By Hélène Caux in Bor, South Sudan