GET - Section 2: Establishment of Projects

Overview

This section aims to facilitate the design of projects for partners and commercial vendors, both new and existing. Its content is part of the annual implementation planning phase and focuses on the establishment of project workplans, grant agreements, UN-to-UN agreements and procurement contracts. See PLAN – Section 8 for more information on the different types of partnership agreements and their components.

In a nutshell

- Operations establish project workplans encompassing results plans, financial plans, and risk registers, aligned with operational priorities and funding allocations.

- They complete all negotiations and finalize contracts with partners and vendors before the project’s effective start date to ensure readiness.

- They integrate risk management and quality assurance mechanisms into planning to mitigate challenges during implementation.

- They prioritize the inclusion of local systems and structures in project design, contributing to sustainable responses.

During the strategic planning phase, an operation decides on the best-fit modalities for implementing its strategy based on the situation analysis, including the stakeholder mapping and theory of change, to inform the partnership selection process. The implementation of projects can be done through a partnership or a procurement contract, or directly by the operation. At the same time, the operation considers whether protection and assistance are provided through cash-based interventions (CBI) or in-kind. During the annual implementation planning, the decisions surrounding the implementation modalities can be revised and documented.

Based on the recommendations of the Implementation Programme Management Committee (IPMC), it may be necessary to amend a partnership framework agreement duration down to the end of the current implementation year, so that there is no creation of a new project workplan for the forthcoming year. The operation informs the partner by 15 October during annual implementation planning for the forthcoming year. See GET – Section 4 for more details.

When developing projects or procurement contracts, it is essential to engage forcibly displaced and stateless people, along with the multi-functional team (MFT) and results managers, who are best placed to identify needs, priorities and modalities of assistance and solutions, in collaboration with UNHCR’s partners.

Furthermore, a key principle in planning, getting and showing results is to secure an effective and contextualized response that reinforces local partnerships, infrastructure and systems, drives self-reliance and resilience, and achieves better protection, inclusion and solutions outcomes for forcibly displaced and stateless people.

Typically, a programme colleague is designated as the partnership management focal point, responsible for the overall coordination of all partnership agreements with a specific partner, while relevant results managers lead the collaboration with the partner on detailed activities in their areas of expertise.

⚠️ ALERT UNHCR collaborates with a variety of partners, whether funded or not. A partner with a project workplan is a UNHCR-funded partner and the relationship is called a “funded partnership”. This section primarily focuses on partners that are provided with funds to achieve results and are referred to here as “partners”. UNHCR engages in partnerships with organizations at the global, regional and national levels with no financial commitments involved. These strategic partnerships are developed in recognition of the respective mandates, responsibilities, and objectives of both UNHCR and its partners, as well as the potential long history of close cooperation between them. These non-funded partners are specifically referenced as such in this section. |

The supply function is responsible for the overall coordination of procurement actions. Each procurement contract has a requesting function, a contract manager, and a contract procurement administrator. The requesting function is a UNHCR section, unit or team responsible for requesting procurement through a purchase requisition, and for specifying the procurement technical requirements. The contract manager, who is within the requesting function and may also be the results manager, is responsible for coordinating and planning the contractual activities with the vendor, as well as tracking and documenting the vendor’s performance against the contract. The contract procurement administrator, typically a supply colleague, is responsible for administrative actions undertaken after the award of a procurement contract.

CBI or in-kind non-food item assistance

When delivering assistance (whether cash or in-kind), a targeting approach is necessary to select forcibly displaced and stateless people eligible to receive assistance. Targeting approaches are based on an understanding of each household’s needs and vulnerabilities and are based on information from the situation analysis and the available assessments.

The parameters for the targeting approach consider age, gender and diversity by ensuring that the protection risk analysis, including the gender-based violence (GBV) risk analysis, informs the targeting to ensure a “do no harm” approach. They are informed by consultations with partners and stakeholders, including forcibly displaced and stateless people and host communities, which can ensure ownership and promote equality. In most situations, it is not feasible to meet all the identified needs during the annual implementation planning due to budgetary gaps or limited reach. In some situations, a coordinated assessment can be conducted to identify the needs and vulnerabilities of households and inform eligibility criteria. For more information, see the UNHCR Assessment and Monitoring Resource Centre. The budget for these assessments may be included in the project workplan or procurement contract.

Cash-based interventions (CBI)

Aligned to the Policy on Cash-Based Interventions, to the extent possible, UNHCR provides unrestricted CBI to meet the well-being and basic needs of forcibly displaced and stateless people. Restricted CBI is only to be considered as a last resort to achieve a specific pre-defined outcome.

When feasible, UNHCR prioritizes the delivery of CBI through commercial contracts with financial service providers (FSPs) that can distribute cash to forcibly displaced and stateless people through bank accounts, prepaid cards, mobile money, or cash over the counter. The procedures for identifying and selecting FSPs are governed by the guidance on procurement.

The risk management tool on cash-based interventions helps to identify CBI-related risks in operations and looks at measures to address them, covering a range of possible risks and relevant proactive or reactive treatments. The main risks to achieving the intended outcomes of CBI identified in the operation’s multi-year strategic plan are assessed and captured in UNHCR’s operational Risk Register under the “risk sub-category 4.1. cash-based interventions”.

CBI implemented by a partner

If direct implementation is not feasible or appropriate, CBI can be delivered through partners with the requisite capacity and expertise, as evaluated against the scoring criteria of a competitive selection process. Standard conditions related to the implementation of CBI activities by a partner are reflected in the project workplan, with the partner’s responsibilities clearly described therein.

To comply with the guidance on the financial management and related risks for cash-based interventions, the partner establishes and documents effective procedures, criteria and financial controls for cash assistance through a standard operating procedure (SOP) developed in consultation with UNHCR. This includes the traceability of funds, project audit trails, controls on key steps of implementation, monitoring of transfers and transactions, and distribution statistics.

In-kind non-food item assistance

Operations continuously work to develop and improve basic needs assistance provided by consulting with affected communities and adopting solutions based on their inputs, and by reducing the carbon footprint of assistance with a sustainable supply chain. Operations also ensure that the delivery of assistance is effective and timely, and considers age, gender and disability.

The risk management tool for the management of non-food items (NFIs) is a resource that assists country operations in identifying and analysing risks related to such activities, and in developing and implementing proactive and reactive treatments to address them.

To facilitate adequate inventory management, country operations are encouraged to develop SOPs for needs-based planning, sourcing, pipeline management, distributions, reallocations and disposal actions. These procedures align with the Operational Guidelines on NFI Management, and ensure that inventory items and stock are handled effectively and efficiently.

Non-food items distributed by a partner

UNHCR often undertakes NFI distributions through funded partners (and occasionally non-funded partners) by using distribution storage points (DSPs). DSPs are intermediary storage points, close to distribution sites that are used to store NFIs before distribution. A DSP is not registered in Cloud ERP and is often managed by the partner.

Operations may transfer control and ownership of its UNHCR-procured NFIs to a funded or non-funded partner. This can either be:

1. NFIs purchased by UNHCR with the express purpose of being transferred immediately to a partner, which is considered a direct transfer.

- For funded partners, in this case, an operation transfers ownership and control through an external Movement Request Issue (MRI) in Cloud ERP, supported by a Goods Received Note (GRN) which is uploaded into Cloud ERP.

- For non-funded partners, a Transfer of Ownership (ToO) agreement is required for all direct transfers. The transfer documentation must be attached to the asset record within Cloud ERP, including a signed ToO agreement.

2. NFIs that have already been in use by UNHCR or by a partner under right of use conditions, which is considered a transfer of an existing asset.

- For both funded and non-funded partners, in this case, a Transfer of Ownership (ToO) agreement is required once approval is obtained from an authorizing officer or Asset Management Board (AMB). Transfers of assets acquired for direct transfers do not need a disposal authorization.

Once the transferred goods are received by partners, these NFIs are no longer considered UNHCR inventory and are no longer under UNHCR’s ownership. Inventories are held in warehouses or could be in transit to the final delivery point. However, once ownership has been transferred to the partner, these items are not expected to be transferred back to UNHCR, nor valued and recorded in UNHCR’s financial statements at the end of the year.

As stipulated within the project workplan (for funded partners) and the Memorandum or Letter of Understanding with a non-funded partner, NFI results are reported against the targets agreed with the partner. Partners do not report on the NFI movement and stock levels because the NFIs are not under UNHCR’s ownership.

It is recommended that funded partners requesting the release of UNHCR stock, provide the following documentation to the relevant UNHCR supply function to support an external MRI for programme approval:

- An NFI distribution plan, including the partner’s current stock availability.

- A distribution list (if applicable) aligned to the standards and principles of UNHCR’s General Policy on Personal Data Protection and Privacy, and the Policy on Information Security.

When UNHCR selects a partner to achieve the identified results, it establishes a partnership framework agreement (PFA) and a data protection agreement, where required (see PLAN – Section 8), before entering into a project workplan. The project workplan is between UNHCR and the funded partner only.

UNHCR establishes a project workplan within the calendar year that stipulates the responsibilities, obligations and accountabilities of the participating parties for undertaking specific activities. It outlines the specific outputs to be achieved through collaboration between UNHCR and its partner by concluding negotiations and formalizing common understandings among involved parties. This type of collaboration entails the transfer of funds from UNHCR to the partner for the delivery of results within a given duration (usually one UNHCR financial year).

To commence a project workplan, an operation initiates negotiations with the partner on detailed activities, results, and financials before mid-October, ensuring alignment with the operation’s strategic plan.

There are a number of standard partnership agreements available in Cloud ERP for use surrounding a financial commitment in accordance with the type of partner. UNHCR and partners agree on and sign a standard contract template downloaded from Cloud ERP. PLAN – Section 8 gives further details on non-standard agreements.

This section looks specifically at the standard project workplan. For further details on the other standard funded partnership agreements, refer to the sections below on grant agreements and UN-to-UN agreements.

The negotiation of a project workplan includes the following additional mandatory components that are negotiated and agreed in Aconex: 1. financial plan; 2. results plan; and 3. risk register. These three components are not annexed to the contract, which includes a financial commitment through a purchase order (PO).

For the development of the project workplan, UNHCR and the partner engage in joint consultations that actively involve the identified target population. This consultation ensures that implementation approaches defined by the partner and UNHCR are culturally relevant and effective and that activities address protection risks with the community’s involvement in implementation. Building on this collaboration, UNHCR and the partner establish risk mitigation control measures, timelines, reporting requirements, and the project details within the project workplan template. Furthermore, the results and financial plans, and risk register are developed.

Risk-based management

Effective management of risks and opportunities associated with the project workplan will contribute to the achievement of the objectives. It is essential to identify the key risks and opportunities across the partnership lifecycle so that UNHCR and the partner can collectively manage them and maximize the likelihood of successful delivery for forcibly displaced and stateless people.

It is recommended that operations capture high-risk partners in the related implementation monitoring commitments within their assessment, monitoring and evaluation workplan. This is completed by the results managers with the MFT, and highlights UNHCR’s roles and responsibilities, the frequency and deliverables of monitoring. See PLAN – Section 6 for more information about the assessment, monitoring and evaluation workplan.

Project workplan risk register

The project control function coordinates with the partner and the MFT to identify risks that could significantly impact the achievement of outputs or deviate from the expected results of the project in order to agree on the content of the risk register.

Each operation and partner aim to prioritize risks by identifying at least three project risks and associated treatment plans within the project workplan risk register before signing the project workplan. The focus is on project-specific risks, including all internal and external factors that may affect the project, and not on assessing the partner's performance. These project-specific risks may be informed by the partner’s ICA or audit recommendations, as applicable. The treatment plans outline mitigation measures to facilitate the achievement of the workplan’s outputs and to enhance accountability for resources entrusted to UNHCR.

For partners processing personal data, the data protection focal point ensures that the risk register captures the highest data protection risk(s) and information security risk(s) that were identified from the data protection and information security capacity assessment. See the External Guidance Note for UNHCR Funded Partners on Minimum Information Security Baseline for more information on this capacity assessment.

See Examples of Risk Registers (EN, FR, ES).

This risk register does not form an annex of the signed project workplan and therefore needs not be signed. However, the project control function approves the risk register, per the project workplan in Aconex, ahead of the project workplan signature.

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: ACONEX The risk register process utilizes the “Document” and “Workflow” modules. Click here for more details. |

Results plan

The results plan contains the complete list of indicators and their targets that the partner will report on for the activities to be implemented under the project workplan, in order to measure the progress and success of these activities. UNHCR shares the results plan with the partner to review, finalize and agree on via PROMS. See Examples of Results Plans (EN, FR, ES).

In case the operation considers including additional indicators in the project workplan that are not in the multi-year results framework in COMPASS, the operation must consider if these indicators are necessary, if the data is required and how it will be used. Should additional indicators be required, they are listed in the “Additional Indicators” tab of the results plan and will not be reported on in COMPASS.

Operations give particular attention to the careful management of core output indicators assigned to partners, with consideration to avoid double counting.

The partner then reviews all indicators and proposes targets, also confirming the data disaggregation that will be reported. The partner may propose a change to user-defined indicators, in accordance with the activities in the project workplan. Any changes to COMPASS indicators agreed upon by the operation within the results plan are then reflected in the partnership scope and multi-year results chain in COMPASS once the negotiation is completed in PROMS. The changes to additional indicators (if applicable) are not reflected in COMPASS.

Both parties negotiate and agree on the results plan in PROMS, however any changes to indicators must be manually adjusted by the operation in COMPASS. Once approved through the PROMS workflow, partner sub-targets are automatically imported from PROMS to COMPASS and auto summed in COMPASS to calculate the total sub-targets (partner + DI sub-total targets).

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: ACONEX The results plan document is registered in the Aconex Document Register after the partnership scope is sent from COMPASS. |

Financial plan

The partner submits the financial plan outlining the resources needed to implement the project. This includes the costs of activities/interventions, assets, human resources etc. The financial plan also demonstrates resources fully covered by UNHCR or by the partner. See the Examples of Financial Plans (EN, FR, ES).

The financial plan and project financial report (PFR) refer to the same account codes used by partners. There are two types of accounts:

1. Direct costs. These are the necessary and reasonable costs incurred in delivering a specific output and arise directly because the activities are required to achieve the specific output. They are divided into two sub-types:

- Direct programme costs. These costs may be 100 per cent directly related to one output. Costs may also be attributed to direct programme costs that are shared over more than one output, but for which both the partner and UNHCR do not want to apply an apportionment automated calculation. For example, a financial plan has three outputs. Two outputs look towards health results, while one output looks to shelter. The partner budgets one health officer over the two shared health outputs but does not want to apportion the same staffing cost to the third output. Therefore, these shared staffing costs may be budgeted using the direct programme account codes within the financial plan for the two health outputs. The bureau guides operations if in doubt about how to share direct programme costs over more than one output.

- Direct shared costs. These are costs that a partner apportions across more than one output under the financial plan of one project workplan. They are also used by the partner when representing a shared cost involving another donor. For instance, if UNHCR does not cover 100 per cent of the overall cost of an item or service, the partner may share this cost with funds provided by another donor and only include the portion of the cost that UNHCR covers in the financial plan. Direct shared costs should be used to the extent feasible, where relevant to the cost.

2. Indirect support costs. These are the costs needed to manage and run an organization. They support the delivery of activities but are not directly related to implementation and can include policies, frameworks, systems, overhead, and capacity-strengthening costs that enable a project or organization to operate successfully. It is not practical to charge indirect costs to individual funding arrangements under direct costs, but without these costs present, projects and programmes cannot be delivered effectively, efficiently and safely. These costs are covered by the partner indirect support costs.

A partner qualifies for a UNHCR contribution towards their indirect support costs when the following criteria are met:

- The partner is a national or international non-governmental organization (NGO).

- The partner enters into a project workplan with UNHCR.

- The partner specifically commits to using the indirect support costs to enhance integrity, accountability, oversight, administration, and other support.

💡 KEEP IN MIND The partner’s methodology for calculating what direct costs will be charged to a project must be transparent and applied consistently throughout a project. See the partnership terms for further details. |

UNHCR does not provide indirect support costs to grant agreement or government partners. For grant agreement partners, this is because the entire budget is a grant, much of which contributes to strengthening the capacity and internal controls of the partner. Government partners do not receive indirect support costs as governments are assumed to have the required structure, funds and oversight. Specific activities related to risk mitigation for a project implemented by a government partner are incorporated into the project as a direct cost.

The partner can use indirect support costs at its discretion to support headquarters, regional and country offices, or other locations, to achieve overall humanitarian objectives and/or project results.

UNHCR’s contribution to the partner’s indirect support costs is calculated based on a flat rate on the overall expenditures of direct costs reported under a project workplan, as follows:

- Seven per cent for international organizations (international NGOs and other not-for-profit partners that operate within and outside their country of establishment, i.e., the country where the organization is incorporated, including those that undertake global programmes from their headquarters location).

- Four per cent for national organizations (NGOs and other not-for-profit partners that operate only in the country where their headquarters are established, excluding organizations holding a grant agreement).

- Inter-agency rates for the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and other UN system organizations at seven per cent, except for UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF and UNWOMEN, where eight per cent may apply.

In exceptional cases where the partner voluntarily chooses not to receive any indirect support costs, the operation documents it for audit trail, and this cost is excluded from the financial plan.

See the Account Codes for Funded Partnership Agreements.

The financial plans are designed per output in COMPASS using the B61A single account code and are linked to only one cost centre. They can be broken down by geographical location where the output is being realized, by selecting the appropriate expenditure organization in COMPASS. Financial plans comprise a single currency, which is typically the currency of the expected predominant expenditure, usually the local currency.

Ineligible costs

The following are examples of ineligible costs, both direct and indirect, that are not charged under UNHCR-funded projects:

- Losses or provision for losses due to fraud and corruption.

- Purchase of land and buildings (unless explicitly agreed in the funding arrangement). A project workplan is never to be used as a mechanism to purchase property or land on behalf of UNHCR. Operations are always required to consult and clear any property purchase with the Division of Financial and Administrative Management (DFAM).

- Interest or debt servicing costs (unless the funds are paid in arrears).

- Costs of raising unrestricted or unearmarked funds.

- Costs of gifts and donations.

- Alcohol costs.

- Entertainment costs.

- Costs directly covered by another funding source or donor.

- Costs related to depreciation of all assets.

Procurement

If a partner has no ICA/Q in the last three years, and/or its last ICA/Q has resulted in a significant or high procurement risk rating, the Implementation Programme Management Committee (IPMC) consults with the supply function about any limitations to be applied to the financial plan regarding procurement (see PLAN – Section 8). Such limitations usually result in the financial plan only including procurement costs related to the partner’s rent, communications, utilities, security, insurance, travel and partner affiliate workforce. These limitations surrounding procurement should continue until the partner improves its procurement capacity and its next ICA/Q results receive a medium or low procurement risk rating.

Final approval of the financial plan will create a PO and a prepayment

Once the partner completes the financial plan, it shares it with the programme colleague designated as the partnership manager. The programme colleague then coordinates feedback and confirmation with the results manager(s) and project control colleagues, so that the project workplan quality assurance checklist can be completed (see below).

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: ACONEX The financial plan document is registered in the “Document Register” in Aconex after the partnership scope is sent from COMPASS. Click here for more details and here for the workaround process. |

For more information on partners reporting on expenditures incurred in a different currency than that of the financial plan, see GET – Section 4.

Partner personnel

During the project workplan agreement negotiation, UNHCR can ask for an organogram or a list of titles and functions that a partner expects to charge to a project. This list does not form an annex of the signed project workplan. See a Sample Partner Personnel List.

There is no standardized contribution cap or limit for partner personnel costs globally. This means that partners can charge or share the costs of staff members who are supporting the project as determined by their human resources rules. Only in exceptional cases, where UNHCR believes with solid reason that the entitlements of partner personnel are excessive, the operation informs the partner that UNHCR will not pay the full cost (e.g., if the partner has an annual bonus scheme for personnel that results in significantly higher salaries).

However, UNHCR does not have a one-size-fits-all approach to this determination. An operation may find it helpful to conduct market research or take advantage of a recent market analysis conducted by another entity such as a partner. In most cases, a partner can estimate or calculate with some accuracy the cost of the personnel that it charges to the project. However, to allow for the possibility that the partner will not be able to estimate that cost with any certainty, an operation may have information (i.e., a market analysis) that could be helpful for project negotiation.

Several options for market research surrounding partner personnel salaries can support operations. These include a) desk research on economic trends, b) a survey or interviews administered by UNHCR directly, and c) a survey commissioned by UNHCR through an experienced consultant or external audit firm.

For agreed positions, the partner has the freedom to change personnel without asking for UNHCR’s approval, if the changes do not alter conditions set out in the project workplan (e.g., when the results at the output level remain the same and the overall project workplan financial plan is not exceeded, respecting the output budget flexibility control allocated to the partner in the contract terms).

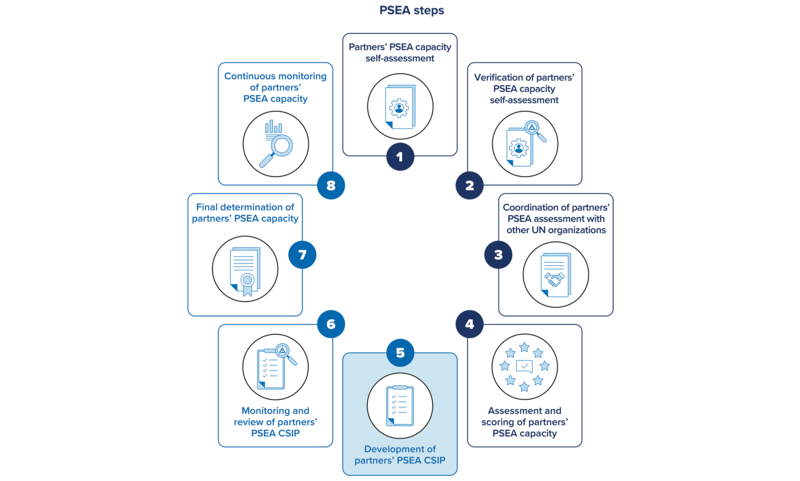

Development of the partners’ PSEA Capacity Strengthening Implementation Plan (CSIP)

For partners that are rated low or medium (meeting 1-7 core standards) in their protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) capacity assessment, the operation may finalize the project workplan for signature with the relevant justification. In this case, the PSEA focal point, together with the designated MFT members assigned for the PSEA capacity assessment of partners, develops a Capacity Strengthening Implementation Plan (CSIP) jointly with the partner to address the remaining gaps. They finalize it in the UNPP PSEA module. The monitoring and review of the partner’s capacity continue throughout the implementation of the CSIP.

Exceptionally, if the partner has no access to the UNPP, the CSIP is developed using the template of the UN Common Tool. Once signed by both UNHCR and the partner, the CSIP is then stored in the operation’s SharePoint, or the PROMS document register for recordkeeping. The template can be accessed from the Inter-agency PSEA Implementing Partner Protocol Resource Package on UNPP.

The plan includes different activities to address the gaps in the partner’s capacity for those core standards that were scored as “no” in the assessment. The following are some examples of required activities that can be added to the CSIP:

- The development of policies that prohibit, prevent and respond to sexual exploitation and abuse.

- A human resources system that includes vetting procedures.

- Mandatory PSEA training for personnel, refugee workers and community volunteers.

- The partner joining a coordinated inter-agency feedback and response mechanism.

- The development of a standard operating procedure for managing allegations and investigation processes.

In the case of a shared partner, UNHCR coordinates the CISP development with the other UN organization. Where a partner has been assessed by another UN organization and there is a CSIP already in place, UNHCR reviews it to ensure that there are no gaps and includes additional activities as needed and applicable to the UNHCR project. More information on the minimum requirements for each core standard and related CSIP activities is available on the Interagency PSEA IP Protocol Resource Package for UN Personnel.

SOFTWARE TIP: UNPP See further guidance on starting a CSIP in PSEA Module User Guides and Resource Materials on the UNPP. |

The UNPP PSEA module also allows the addition of activities in the CSIP for core standards that are scored as “yes”, in case the operation agrees with the partner on additional activities. These activities and their completion will not affect the scoring and final determination of the partner’s capacity.

UNHCR partners may use the indirect support costs in the financial plan to implement CSIP activities. Additional support may be provided to the partner, for example, by including them in trainings or networks of UNHCR or other UN organizations. See the Resources to support PSEA capacity strengthening for more guidance and support materials that can help the partner in implementing the CSIP activities.

Assets for partners

The Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) service has developed the Inventory and Asset Management tool to assist field operations in mitigating risks when managing inventory, including fleet and fuel. The tool is designed to ensure that an operation adequately identifies and analyses key risks and considers agreed-upon relevant treatments (proactive and reactive).

Assets for partners are defined as any goods or property used to implement a project, excluding those owned before the partnership or obtained from other third-party sources.

A partnership may require assets to achieve the agreed results. Assets may either be:

a) purchased by a partner with UNHCR funds, or

b) provided to a partner by UNHCR.

Goods and property bought by a partner with UNHCR funds are not reported on or physically verified by UNHCR. Similarly, assets previously controlled and owned by UNHCR (i.e., previously included in the UNHCR asset list in Cloud ERP) that are provided to a partner or third party under a transfer of ownership agreement, are also not required to be reported, nor verified. These assets remain under the ownership and control of a partner and will not be returned to UNHCR once the project ends.

Right of use conditions

All partners to whom UNHCR gives the right to use vehicles and/or generators submit monthly vehicle and generator data, including mileage, fuel, maintenance, and repair costs. For the sharing of vehicle tracking system (VTS) data with partners or vendors, the third party can be granted limited access to the VTS based on the conditions and scope set out in the relevant project workplan.

The internal controls assessed (ICQ/ICA) include the partner’s general asset management framework, systems and processes in place, with further monitoring through the project financial verification process. When challenges surrounding asset management are identified, including for assets purchased by a partner and funded through UNHCR’s contribution, they are raised, via “Implementation Monitoring” in Aconex for the partner to follow up (see GET – Section 4 for raising Field module Issues).

For details surrounding partner vehicle insurance, please refer to the Right of Use articles in the partnership agreement.

Project workplan contract

During the annual implementation planning, key stakeholders collaborate to design and develop detailed activities. This is documented within the project workplan contract template. See Examples of Project Workplans (EN, ES, FR).

The partner is responsible for developing the project scope and details, alongside the UNHCR operation, which outline how they plan to implement the activities. Results managers and the MFT review the project scope and details and provide feedback.

The project workplan contract specifies how forcibly displaced and stateless people participated in the project design, as well as the mechanisms in place to ensure their meaningful participation throughout implementation. This ensures that their views are included in the project and its revisions and that there is a swift response to reported cases of mismanagement or misconduct, including sexual exploitation and abuse.

Determining essential controls

The programme function consults project control for the identification of the essential controls to be applied within the project workplan. These essential controls are informed by the partner’s UN audit results, including the internal control assessment or questionnaire (ICA/ICQ) risk rating. The UNPP provides information on the partner’s risk profile, including the latest UN project audit and the ICQ risk rating, where available.

The head of sub-office, representative or director has the authority to alter the controls within the project workplan during contract negotiation, taking into account the context, project developments, or other reasons documented within the project workplan, as additional factors considered under essential controls.

Other key sections of the contract

The dates of the implementation period specified within the project workplan contract determine the budget year in which the agreement must be considered for budget consumption purposes. This informs the determination of partnership-related commitments or pre-payments to be recorded in UNHCR accounts in compliance with UNHCR’s Accounting Policy Framework.

The resources and results are summarized in the project workplan contract once the negotiation of both the results and financial plan have been discussed with the partner.

UNHCR assets are listed alongside their descriptions and the estimated date of handover. All project assets are agreed upon and budgeted within the financial plan.

Partners who will process the personal data of forcibly displaced and stateless people need to sign a data protection agreement (DPA) (see PLAN – Section 8). The project workplan contract template details the particulars of processing personal data, including the legitimate basis for collecting and sharing, the nature and purpose of processing, and the types of personal data. The data protection focal point (DPFP) is responsible for reviewing the processing particulars.

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: ACONEX The project workplan contract is developed jointly with the partner in Aconex. Click here for more details and here for the workaround process. |

Quality assurance and signature of a project workplan

The signature of a project workplan ahead of the effective start date of implementation is critical. Thus, operations are required to finalize agreements with funded partners before implementation starts. If an operation envisages that a project workplan will not be signed ahead of the effective start date, the UNHCR signatory to the project workplan reviews the situation and documents any exception leading to the delayed signature. Such documentation considers if:

- There is a risk that the agreement will not be successfully finalized and executed according to the terms already discussed and understood by all parties.

- Failure to start implementation by the partner in a timely manner would result in a disruption of critical protection activities.

The project workplan, financial plan and results plan are shared with the project control function, or colleagues with designated project control responsibilities, for the quality assurance review. The project control function conducts this review before approval and signature of the project workplan, as well as before approval of the financial and results plans in PROMS, through the completion of the Project Workplan Quality Assurance Checklist, which is stored in PROMS.

The project workplan is signed with the respective partner and processed in Cloud ERP and PROMS only, and never offline. Operations may enter into non-standard agreements with funded partners that include deviations to the terms and conditions of the standard partnership agreement templates only after clearance of headquarters.

Transfer of first prepayment for project workplan

The expected prepayments are calculated during the development of the financial plan, based on the determined essential control measures incorporated in the project workplan contract, as described above.

The first prepayment is transferred in a single currency to the authorized bank account held by the partner and within the applicable timelines. The disbursement of subsequent prepayments is subject to the availability of funds, the receipt of accurate reports from the partner, the timely implementation of activities, the cash flow needs, and the resource requirements estimated for the following months. If UNHCR anticipates funding challenges, the partner is notified as soon as possible.

The bank account, whether pooled or dedicated, does not need to be in the same country as the project. When UNHCR transfers a prepayment to the partner in the currency of the project workplan, the amount that the partner receives in its pooled bank account, in the currency of the pooled bank account, depends on the exchange rates used by the bank.

The purchase order and first prepayment invoice are created via integration once the results and financial plans have been approved on their respective workflow in PROMS, with an active contract in Cloud ERP. See the Video Tutorial: Search for PO and prepayment in Cloud ERP.

UNHCR strives to promote the role of grassroots organizations or groups in responding to challenges related to forced displacement and statelessness, aiming to contribute by way of a grant and through capacity strengthening for the work of such organizations or groups.

The grant agreement brings an indirect contribution to the overall advancement of UNHCR’s mandate and is designed to empower groups led by forcibly displaced and stateless people, without creating a dependency on UNHCR funds. Strengthening engagement with community-based organizations, including those led by women, is a key programming principle that underpins several UNHCR Focus Area Strategic Plans.

A grant agreement facilitates a one-off payment of no more than USD 12,000 per partner per year, which may be issued as a single grant or multiple smaller ones. Unlike standard partnership funding arrangements, UNHCR grants do not require implementation or financial reports, financial verification, or the return of unused funds, falling under the category of transactions without binding arrangements per IPSAS 48. Grant agreements differ from regular partnerships in that they do not require financial, or results planning and are not integrated into Aconex.

A grant agreement partner is an organization or group where individuals with direct lived experience of forced displacement or statelessness hold primary leadership roles, and whose stated objectives and activities focus on responding to the needs of forcibly displaced and stateless people and communities hosting them. The grant agreement partner may also be a community-based organization from the communities hosting forcibly displaced and stateless people, whose stated objectives and activities focus on responding to the needs of forcibly displaced and stateless people and the communities hosting them.

Operations are encouraged to inform relevant communities about grant agreement opportunities with UNHCR. An operation may choose to conduct a competitive selection process to establish a grant agreement, either for a one-time activity or for recurring activities in a multi-year plan. This process is optional. Community-based organizations can register on the UNPP to apply for a grant agreement, though it may prove too difficult for a grant agreement partner with no formal status. Applications can be made in response to a call for expression of interest on the UNPP or through different communication channels but can also be submitted unsolicited. See the Grant Agreement Concept Note Template.

Grant agreement partners are exempted from a PSEA capacity assessment, an internal control assessment, a data protection and information security capacity assessment and from being project audited. However, PSEA and other safeguards are included in the eligibility criteria which must be reviewed by the programme function, alongside the supporting documentation provided.

Selected grant agreement partners are registered in Cloud ERP. The grant agreement partners enter their details with the Cloud ERP Grant Agreement Registration Form, completing Part B - Self-Declaration in case they are not registered on the UNPP. If these organizations lack legal status in the country in which they operate, UNHCR may award the grant to an individual representing the organization. See the sample of the Certificate of Authority.

The agreement consists of:

- The grant agreement, including the activity details, budget and reporting deadline.

- The general conditions of contract for grant agreements (the "General Conditions"), as Appendix 1 to the grant agreement.

- The code of conduct template as Appendix 2 of the grant agreement.

Ahead of signature, the project control function reviews the grant agreement alongside the eligibility checklist for quality assurance purposes, signing on completion. The standard quality assurance checklist is not applicable to grant agreements. Upon signature of the agreement, UNHCR makes a single payment to the partner for the full amount noted in the grant agreement. UNHCR is not obliged to make any further payments under one agreement.

Deepening partnerships with other UN organizations is one of the five priority actions of the Focus Area Strategic Plan on Engaging Development Actors. This entails operations ensuring that relevant organizations’ country programmes include forcibly displaced and stateless people, leveraging global commitments made at the executive boards of UN development organizations to share responsibility.

Joint programming is a way to achieve a catalytic development result that depends upon the comparative advantages of two or more participating UN organizations, working together with partners as a team in a coordinated and integrated manner. Joint programmes strive to contribute to one or more United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) outcomes, national development priorities and related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In addition, they focus on one or more policy levers with the potential to catalyse systemic change. A joint programme can be at country, regional or global levels. See the Guidance Note on a New Generation of Joint Programmes for more information.

The UN-to-UN transfer agreement template is used by UNHCR colleagues in operations for all transfers to another UN organization undertaking programme-related activities. The template is not to be used to transfer funds for authorized administrative activities such as the cost-sharing of an office building, inter-agency secondments, or the secondment of UNOPS personnel, all of which are managed under separate contractual templates. In cases where UNHCR is the recipient agency, then the contributing agency will provide UNHCR operation with an editable UN-to-UN transfer agreement template.

The UNHCR operation then negotiates the UN-to-UN agreement with the following components:

- The UN-to-UN transfer agreement template is downloaded from the Cloud ERP “Contracts” module, by selecting the “UN Agreement” template from the terms library.

- A financial plan is automatically generated in PROMS via integration, attached to the contract as Annex A: Budget.

- A results plan is optional, depending on the type of activities required. If required, results can be negotiated using the results plan template that is automatically generated in PROMS via integration (like the financial plan) and added as an additional annex.

- A risk register is optional and contingent upon the nature of the project. The decision to draw up a risk register is made by the operation (project control together with programme and the multi-functional team) and in consultation with the UN partner. The need for a risk register is based on identifying risks or opportunities that could significantly impact the project's outputs or cause deviation from expected results. For example, a risk register may be critical for construction projects, but less so for joint UN programmes, or research projects where risks and opportunities, as well as treatments involved, may be minimal. Treatment plans for example, within a risk register, may simply outline existing UN standards already adopted. The risk register should form part of the technical project documents exchanged between the parties, but it is not included as an annex to the UN-to-UN transfer agreement.

For a UN-to-UN agreement, the quality assurance process is essential. The project control function reviews the quality of the agreement in advance of the approval and signature of the contract, as well as before approval of the financial plan and results plan (if applicable) in PROMS and the finalization of the risk register (if applicable).

A UN-to-UN agreement is not subject to project audits nor financial verifications. Other than this, the same principles that apply to a project workplan, also apply to a UN-to-UN agreement unless otherwise stipulated.

To realize its strategic vision, UNHCR has contracts with commercial suppliers that offer goods and services. In general, UNHCR defines a procurement contract as a legally binding agreement between UNHCR and a vendor with established terms and conditions of a procurement action.

Procurement contracts cover the following categories:

- The purchase of goods and/or services (including, but not limited to, telecommunication and IT services, cash-based interventions, construction, banking, transport, warehousing, insurance, travel management services, security services etc.).

- The lease and acquisition of real property (including UN common premises).

The requesting function defines the technical specifications for the procurement needs, known as the requirement definition, which determine the criteria for the technical evaluation of bids from tenders that then leads to the awarding of the contract. If the technical specifications are not clearly and strategically defined, it can pose risks such as inadequate bid submissions, contract amendments, budget implications and confusion regarding the scope of work. See 2.1 Establishment of projects for definitions of the requesting function, contract manager and contract procurement administrator.

There are multiple risks involved in every step of the procurement process, from the mismanagement of the procurement and the sourcing of the wrong product to fraud and corruption. All have the potential to significantly hamper UNHCR’s programmes and discredit its reputation.

The General Policy on Personal Data Protection and Privacy regulates the management of personal data of forcibly displaced and stateless people in a procurement contract.

The general conditions in the goods and/or services contracts include an article on PSEA stating that vendors take all appropriate measures to prevent their employees and any other person engaged and controlled by the vendor from getting involved in sexual exploitation or abuse. Any breach of these provisions entitles UNHCR to terminate the contract immediately upon notice to the vendor, without any liability for termination charges or other liability of any kind.

The United Nations Global Marketplace (UNGM) is the procurement portal of the UN system that brings together the UN procurement personnel and vendor community. UNGM acts as a hub where potential vendors register with all UN organizations and receive information across the UN system and alerts about upcoming tender notices. It is also an important procurement tool for shortlisting vendors during competitive bidding.