PLAN - Section 8: Partnership Engagement

Overview

The impact of UNHCR interventions is vastly magnified by its partnerships with other organizations. Some partners bring specialized expertise, others have a dedicated local workforce with unparalleled knowledge of the context and communities, and some have networks of influence that are invaluable for mobilizing wider support. These partnerships are critical to UNHCR delivering results for forcibly displaced and stateless people.

In a nutshell

- The Implementation Programme Management Committee (IPMC) determines the most appropriate implementation modality.

- The IPMC considers implementation by local actors (including support to the government), NGO partnerships, or direct implementation (which may include commercial contracts).

- The process for the selection of appropriate implementation modality includes tools like the theory of change, stakeholder mapping, and cost-benefit analysis. They help evaluate comparative advantages, mitigate risks, and ensure that the operational goals align with inclusivity, sustainability, local engagement, and strategic workforce planning.

- There are position statements and good practices available to guide operations in effective funded partnerships with government entities.

- Partners can be selected competitively or directly, and their capacity in terms of protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA), data protection and information security (DPIS) and internal controls (ICA/ICQ) is assessed ahead of signing a project workplan.

- There are several types of standard UNHCR partnership agreements applicable to different types of partners and for either a multi-year or shorter duration. Non-standard partnership agreements require the approval of headquarters.

UNHCR collaborates with both funded and non-funded partners at global, regional and national levels. It is important to distinguish between these two types of partnerships while ensuring that they complement each other, rather than exist in parallel.

⚠️ ALERT An organization can be both a funded and a non-funded partner of UNHCR. For example, if it has made a Global Refugee Forum pledge to include refugees in its livelihood programmes, which are not funded by UNHCR, the funded partnership takes this into consideration. |

💡 KEEP IN MIND This section mainly focuses on the process of selecting and concluding agreements with partners funded by UNHCR. However, engaging with a variety of partners, including development actors and the private sector, through non-funded partnership approaches, is equally important and encouraged by the multi-stakeholder approach of the Global Compact on Refugees, the UNHCR Strategic Directions 2022-2026 and the related focus area strategic plans, especially those on Engaging Development Actors and for Climate Action, and the Secretary General’s Action Agenda on Internal Displacement. |

Types of partners

UNHCR works with a diverse range of partners, including but not limited to:

i. Non-profit organisations

ii. Governments

iii. Development partners and international financial institutions

iv. Private sector partners

v. United Nations organizations

Definitions can be found in the UNHCR Programme Glossary List for Partners.

💡 KEEP IN MIND It is important for programme colleagues to familiarize themselves with the legal requirements for non-profit organizations in their country of operation, including the registration process and authorization to operate within the areas where forcibly displaced and stateless people reside. |

A letter of understanding (LoU) can be used by an operation and a non-funded partner to document their cooperation at the country or regional levels. However, LoUs do not address funded relationships or implementation, which are covered by project workplans or standby partnership arrangements. Country-level LoUs require clearance from the Legal Affairs Section (LAS). LoUs and regional memorandums of understanding (MoUs) are shared with relevant technical specialists at headquarters. Country operations and bureaux inform the Governance and Partnership Section of the Division of External Relations (DER) of any MoU or LoU under development.

UNHCR implements activities directly or through funded partnerships. Definitions of funded and non-funded partners can be found in the UNHCR Programme Glossary List for Partners.

💡 KEEP IN MIND A relationship that can be described as “party X does something for party Y so that party Y can achieve its objective” is a commercial arrangement, not a partnership. IPSAS notes that in exchange transactions, one entity receives assets or services or has its liabilities extinguished, and directly gives to another entity approximately equal value, primarily in the form of cash, goods, services, or use of assets. A partnership is a relationship that can be described as “party X does something, and party Y does something for both parties to achieve their objectives”. In such non-exchange transactions, an entity either receives value from another entity without directly giving approximately equal value in exchange or gives value to another entity without directly receiving approximately equal value in exchange. |

Commercial entities registered legally can apply for procurement tenders to position themselves as the best-value-for-money vendor of goods or services. Where the operation determines a vendor is best-fit, a supplier or service provider is selected based on their ability to deliver goods or services and offer the best value for money, rather than their future growth or stability. Some vendors may also prioritize corporate social responsibility outcomes, which makes them suitable partners instead of just vendors. This could lead to a private partnership agreement with UNHCR.

Equally, an organization with an operational presence in areas where forcibly displaced and stateless people are located may provide a service (e.g., a vehicle workshop). This gives it an advantage over commercial entities that have no presence in these areas. While UNHCR retains full control over the programme design and operational decisions, the organization is better equipped to provide goods and/or services. In this case, the partnership is more of a goods and service contractual arrangement, but the partnership principles and tools are still applicable.

Operations may encounter ambiguity in distinguishing between emerging modalities of partnership and commercial engagement. When faced with such uncertainties, operations should consult with their bureaux, which can provide support and guidance on how to navigate these situations.

UNHCR may determine that implementing directly, including procuring services, goods and human resources, is the most appropriate modality for delivering a result. This requires strategic workforce planning to understand the existing capacity within the operation and may involve additional support from technical colleagues. In this case, HR creates a workforce plan (see PLAN – Section 7) and the supply function revises the consolidated procurement plan (CPP) during strategic planning. See below for more details on the consolidated procurement plan (CPP).

💡 KEEP IN MIND Important questions to consider when selecting the best-fit implementation modality are:

|

Implementation Programme Management Committee (IPMC)

All operations entering into funded partnerships establish an Implementation Programme Management Committee (IPMC) that makes recommendations to the head of sub-office, representative or director on:

- Best-fit implementation modalities, including factors surrounding comparative advantages regarding general procurement, taking into consideration the operation’s capacity, context, and strategic workforce planning.

- The selection of partners for undertaking funded partnership agreements.

- Not entering a competitive selection process in certain situations, where direct selection is applicable.

- Any limitations that should be applied to the project workplan regarding procurement in cases where a partner’s internal control assessment (ICA) or internal control questionnaire (ICQ) results in a significant or high procurement risk rating.

- Exceptional termination of a partnership framework agreement at the end of the current implementation year, which would result in no creation of a new project workplan for the forthcoming year.

The committee is appointed by representatives and directors and includes, at a minimum, a chairperson, two members from different functional areas, and a secretary. The size of the IPMC should be representative of the operation and include UNHCR colleagues from field offices and sub-offices, where relevant. Additional ad-hoc experts (e.g., on statelessness) may be invited. Community representatives may also participate as observers, as appropriate. Representation is aligned with UNHCR’s diversity, equity and inclusion strategy. Furthermore, the IPMC may have the same chair and membership as the Local Committee on Contracts (LCC), with the secretary for the IPMC being a programme function, and an alternate from a project control function.

In smaller country operations without an IPMC, the relevant responsibilities are assumed by the two most senior MFT members, who present recommendations verbally to the representative and document only the overall decisions.

⚠️ ALERT A smaller operation typically refers to an Area of Budgetary Control (ABC) with a budget estimated to be below USD 1 million during annual implementation planning for total partnerships in a year. Bureaux work with country operations to confirm whether the IPMC requirement applies, based on this criterion, and having assessed risk through consideration of trends in the number of partnership agreements, staffing capacity, and audit recommendations surrounding partnership management. |

The IPMC relies on the situation analysis and the theory of change to gain a strategic overview and understanding of both current and potential partners. This includes international and local organizations, as well as commercial entities, and their respective impact on the situation of forcibly displaced and stateless people. The IPMC identifies organizations’ general comparative advantages where they may have greater operational efficiency, cost savings, awareness of local conditions, technical expertise, and access to areas that UNHCR cannot reach due to security concerns.

The IPMC prioritizes the following implementation modalities:

- Supporting the development and strengthening of national systems and related public institutions to include forcibly displaced and stateless people in public services.

- Supporting national and local responders, including the government, in their efforts to become more sustainable and impactful.

- Giving individuals and communities the greatest consideration for their capacity, agency and dignity in meeting their needs and reducing barriers to accessing rights, assistance, and services.

The Risk Management Tool for funded partnership management can support the IPMC decision-making processes. The tool, developed by Enterprise Risk Management (ERM), aims to help operations identify and analyse possible risks when implementing projects together with partners. The tool also lists relevant proactive and reactive treatments that operations can consider, choose from, and adapt to their context. Therefore, the tool comprises several generic risk events and opportunities related to funded partnerships, with examples of causes, consequences and treatments that may apply in an operation.

CBI or in-kind assistance

Whether UNHCR is providing assistance directly, or through partners, a clear targeting and prioritization strategy should be defined and agreed upon with partners. See the UNHCR Assessment and Resource Centre for further guidance.

The Policy on Cash-Based Interventions emphasizes UNHCR’s commitment to prioritize the dignity of affected communities while meeting their basic needs. From emergency preparedness and response to achieving solutions, cash-based interventions (CBI) provide forcibly displaced and stateless people with greater dignity and autonomy in meeting their needs. In environments where social, political, security, market, and currency stability conditions are adequate, UNHCR prioritizes CBI over in-kind assistance, in accordance with the “why not cash” approach. It ensures that CBI is included (if feasible) in multi-year strategies, including its resource requirements and allocation. UNHCR also works closely with partners to achieve its CBI outcomes.

Procurement comparative advantages

Considering the best-fit implementation modalities also involves results that require the procurement of goods and services.

💡 KEEP IN MIND If an operation forms a view that a partner is better placed to procure medicines and/or medical supplies than UNHCR, then the supply function submits a request for approval from the senior regional public health officer, the Supply Management Service (SMS) and the Chief of Public Health in the Division of Resilience and Solutions (DRS). See UNHCR’s Essential Medicines and Medical Supplies Guidance for further details. For partners to procure core relief items (CRIs) and/or vehicles, the operation may request approval from DRS/SMS. All requests include a valid justification, evidence of the partner’s comparative advantage, and consider environmental sustainability implications and the carbon footprint. |

The IPMC reviews the operation’s strategic workforce planning and the CPP to consider the operation’s current and future supply function capacity, and the planned multi-year results, and to identify the partners’ comparative advantages for procurement. To assist operations in the latter, a cost-benefit analysis may be helpful, comparing the benefits and costs of UNHCR procuring goods and services versus an organization. The IPMC makes recommendations to the head of sub-office, representative or director, and these decisions are subject to annual review.

The IPMC meeting minutes document considerations regarding implementation modalities, including the comparative advantages for procurement. These IPMC minutes are archived for audit purposes in the operation’s SharePoint.

Procurement planning

During strategic planning, results managers, and supply and programme colleagues convene to analyse UNHCR’s current procurement patterns and ongoing requirements.

💡 KEEP IN MIND Difference between supply chain planning and procurement planning

|

There are four fundamental procurement principles in accordance with the UNHCR Financial and Administrative Policies, Instructions and Procedures:

- The best value for money

- Fairness, integrity, and transparency

- Effective international competition

- The best interest of UNHCR

UNHCR’s procurement planning process has two main outcomes: consolidated procurement plans (CPPs) and individual procurement strategies and plans (IPSP). See GET – Section 2 for more information on IPSPs.

Consolidated Procurement Plan (CPP)

The CPP is a tool that encompasses all procurement actions planned directly by UNHCR. The CPP does not need to be developed afresh at the beginning of every multi-year strategy because there may already be ongoing framework agreements in place in the operation. It is a living document, regularly revisited and revised, including during annual implementation planning. The CPP does not include procurement planned to be delegated to partners. See the partner’s procurement capacity section below.

After completing the stakeholder analysis and determining the best-fit implementation modalities, the supply function coordinates and updates the CPP.

Climate action and procurement

UNHCR is committed to climate action, ensuring an efficient and responsible supply network and a greener end-to-end supply chain. UNHCR prioritizes sustainable products in procurement, including their contents, packaging, transport, use and end-of-life management.

CBI and procurement

The preferred method of delivering cash-based interventions (CBIs) is through financial service providers (FSPs) or, less frequently, through UNHCR’s workforce, as per the Policy on Cash-Based Interventions. To achieve this, UNHCR may encourage FSPs to submit Global Refugee Forum pledges related to general access to bank accounts and financial services. Partners, particularly local ones, may play a critical role in assessment, response analysis, targeting, community outreach and monitoring.

In some contexts, operations may decide to distribute cash through a partner. In such cases, the call for expression of interest includes technical scoring criteria regarding a partner’s CBI procedures, data protection measures, and financial controls for cash assistance, in compliance with the guidance on Financial Management and Related Risks for Cash-Based Interventions and the section below on partnership selection.

The selection of a best-fit partner is guided by IPMC recommendations and, depending on the operational circumstances, may be achieved with or without a formal call for expression of interest (CfEoI).

💡 KEEP IN MIND The Global Compact on Refugees re-states the primary role of host governments in coordinating comprehensive responses for refugees. The host government’s view on the actors who should play a role in responding to the needs of forcibly displaced and stateless people is a valid – though not binding – consideration for the operation when making decisions on the selection of partners and when designing activities to be implemented through partnerships. Even though host governments are not part of the IPMC, their views provided through the situation analysis and stakeholder mapping can inform the IPMC decision-making process. |

UN Partner Portal (UNPP) and due diligence

The UNPP offers organizations a digital space to create an organizational profile, upload documents and provide key information to enhance their visibility to the UN. It is accessible in English, French and Spanish.

Registration on the UNPP

Organizations seeking partnership opportunities with UNHCR register on the UNPP and complete a self-declaration of eligibility. The registration process includes basic identification and legal status details, self-declaration, and acceptance of terms. The UN verification process is often connected to the partnership selection process, as this is required before signing a project workplan.

Government partners, private sector partners, and UN organizations are exempt from UNPP registration.

SOFTWARE TIP: UNPP The UNPP website offers detailed guidance, including on login and navigation, management of a call of expression of interest and partner management. |

All UNHCR colleagues can access the UNPP using their UNHCR e-mail address. However, if they need a more advanced role to fulfil their IPMC-related responsibilities, the operation can contact their bureau.

In exceptional cases, an offline process may be used by the partner to register with UNHCR, with the operation’s support. The operation shares the CfEoI with the prospective partner, alongside any relevant templates. The prospective partner then submits to the operation the required documents, such as the concept note, the protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA) capacity self-assessment and the partner data protection and information security self-assessment, using the corresponding templates. If shared offline, these documents are not visible to other UN organizations. The justification for such an exception is documented and archived for audit purposes on the operation’s SharePoint.

There are various roles in the UNPP for reviewing concept notes, preparing and presenting information to the IPMC and selecting partners.

Verification and due diligence

An organization creates a profile on the UNPP before submitting a concept note for a partnership opportunity. A partner self-declaration is required and covers discrimination, sexual exploitation, sanctioned entities, fraud, corruption, terrorism, trafficking, internal misconduct, bankruptcy, liquidation, tax and legal compliance. Any participating UN entity can review the information submitted by the organization and conduct a due diligence verification. While not mandatory to submit a concept note to a UN organization, UN verification and due diligence are necessary for UNHCR partnership selection.

The UNPP system automatically screens profiles of organizations registered in the UNPP against the UN Security Council sanctions lists, and UN agencies share partnership risk information. A “verified” status indicates that the organization meets minimal due diligence requirements to operate lawfully in the country, has a mandate that aligns with the UN’s mission, has measures to safeguard resources and forcibly displaced and stateless people, and poses no unacceptable reputational risks to the UN. However, verification does not imply competence in a sector or geographic area, nor does it guarantee suitability as a partner for UNHCR. It only means that the organization has met the UN due diligence requirements.

⚠️ ALERT “Raising a flag” on the partner’s profile on the UNPP If headquarters establishes that a partner has failed to meet important obligations under a partnership agreement regarding financial requirements, PSEA, ethics, integrity and investigations, a flag is raised on the partner’s profile on the UNPP. Depending on the type of flag, the operation seeks guidance from headquarters on whether to continue considering the organization’s application in the selection process. |

Direct selection

Based on the recommendation of the IPMC, a head of sub-office, representative or director has the discretion not to release a CfEoI for any relevant sector, outcome, or location when:

- The identity of the most appropriate partner is already known. This may be evident from the theory of change and stakeholder mapping conducted during multi-year planning. This can be the case when the partner is an organization with a unique attribute and/or mandate, specific expertise or is the only possible and available entity to deliver the intended results.

- The potential partnership budget is estimated not to exceed USD 100,000 for a partner within one calendar year.

- A private sector entity is considered for a partnership, which usually involves a different approach compared to engaging an organization or government partner. The intention of the partnership may originate from UNHCR or the private sector entity.

The operation must be able to fully justify selecting a partner in a non-competitive manner.

Following an emergency declaration, the representative holds the authority to temporarily suspend competitive selection without a recommendation from the IPMC. After the emergency declaration expires, the representative revisits the implementation modalities with the IPMC prior to the next year of implementation.

An organization can be directly selected via the UNPP. The UNHCR operation UNPP user initiates the UNPP workflow for the creation of a direct selection partnership opportunity. The use of the UNPP to log direct selection partnership opportunities provides several benefits. It ensures that all necessary due diligence and screening are conducted on the partner, and it allows for greater sharing of partnership selection data with other UN organizations. Justification for the use of direct selection is documented by the IPMC for audit purposes on the operation’s SharePoint.

💡 KEEP IN MIND Certain partners are exempt from the competitive partnership selection process, including UN organizations, government institutions with specific mandates, and individuals or organizations considered for a grant agreement. |

Unsolicited proposals

Organizations have the option to propose their own initiatives through an unsolicited concept note, even if there is no active CfEoI. If the operation sees merit in the initiative and it aligns with its strategy, the IPMC considers whether a competitive selection process is appropriate, taking into account the theory of change and situation analysis, including the stakeholder analysis.

Competitive selection

Operations may periodically survey the area of operation to identify one or more organizations they wish to partner with. It is good practice to do this shortly after the multi-year strategic plan has been submitted and as part of the PLAN for Results phase.

It is also good practice to identify a pool of potential partners as part of contingency planning if the annual risk assessment reveals a high risk of a new or escalated emergency, and existing partnerships are judged inadequate to respond to the likely emergency in terms of capacity, location, and scope of projected emergency response activities. For more information, see GET – Section 5.

💡 KEEP IN MIND It is recommended that the competitive selection process (from issuing the call for expression of interest to communicating the decision on selection to applicants) does not exceed three months. |

Calls for expressions of interest

The UNPP’s calls for expression of interest (CfEoI) aim to attract partners who can collaborate with UNHCR and contribute their expertise, resources and support to achieve common results. The call provides prospective partners with key information on the partnership opportunity, including project scope, selection criteria, duration, deadlines, and geographic coverage, aligned with the multi-year strategy. It must include UNHCR’s areas of specialization for partners that are available on the UNPP and outlines key sector-specific policies, standards and guidelines with which partners are expected to comply with, be guided by, or explain their omission. The call may include questions surrounding capacity assessments (excluding the PSEA assessment), and UNHCR may prescribe how the results are to be achieved or invite innovative delivery mechanisms. See a Sample Template for a Call for Expression of Interest (EN, FR, ES).

A CfEoI, that looks for partnerships that will likely include processing of personal data of forcibly displaced and stateless people, requires partners to adhere to UNHCR’s policies on Personal Data Protection. Such CfEoIs will therefore specify whether the project involves a Controller to Controller (C2C) or Controller to Processor (C2P) model with respect to the processing of personal data in connection with the activities to be performed. The CfEoI will furthermore request any applying organization to complete a self-assessment of their data protection and information security capacity, to be submitted alongside their concept note. See the Partner Data Protection and Infosec Self-Assessment.

See below for more information surrounding a partner’s data protection and information security capacity.

The CfEOI template outlines that the partnership duration is contingent on partner reviews (performance and financial, including project audits), pending open receivables, changes in context, compliance with partnership framework agreements and project workplan terms, willingness to work within the scope, and feedback from affected communities that is in line with UNHCR’s Policy on Age, Gender and Diversity.

Selection criteria

Calls for expression of interest have weighted criteria for selection that are developed by results managers with input from the MFT. Interested organizations demonstrate their comparative advantage and value via a concept note, with criteria specific to each opportunity. It is recommended that the following criteria be utilized in the UNPP for UNHCR selection:

- Sector expertise and experience

- Project management

- Local experience and presence

- Accountability to communities and community relations

- Cost-effectiveness

- Access/security considerations

In line with UNHCR’s commitment to localization, it is recommended that operations do not incorporate weighted criteria surrounding the partner’s “contribution of resources” but rather look at the overall cost-effectiveness in consideration of best value for money.

Technical expertise such as health, gender-based violence, child protection, legal assistance, and disability, are also among the criteria.

💡 KEEP IN MIND Conditions and project requirements may affect the selection criteria. For example:

|

Dissemination

The programme function is responsible for publishing the CfEoI on the UNPP in a timely manner. Further dissemination of the CfEoI may be explored via social media promotion of the UNPP link, outreach to civil society platforms, or other relevant communication platforms (humanitarian, development, government), considering the local context.

The same information and general clarifications are provided to all existing and potential partners via the UNPP at the same time and with the same deadline to ensure fairness and objectivity in the process. A UNPP CfEoI is open to organizations for a minimum of four weeks.

Concept notes

The operation uses a standardized concept note template, or tailors the template to its context when launching its CfEoI to help applicants familiarize themselves and to ensure consistency and objectivity. The scoring criteria are then tailored and weighted accordingly and entered into the UNPP against the above five selection criteria. UNHCR aims to make the application process accessible to all organizations, regardless of size or capacity and considers ways to make it easier for them. The complexity, length, language, or format of the concept note is not to be a barrier for organizations interested in applying.

💡 KEEP IN MIND Operations may wish to include the following options in the selection criteria:

|

Organizations may be asked for supporting documentation with their concept note, but requests are minimized to avoid disadvantaging less experienced local organizations. Operations can refer to the organization’s profile on the UNPP, which already contains useful information, including assessments by UNHCR and other UN organizations. See the Sample Concept Note Template (EN, FR, ES).

Conducting the technical evaluation

The MFT evaluates concept notes based on the criteria, led by the results manager or delegate, with representatives from programme and project control. Conflicts of interest among those involved in the evaluation are declared to the IPMC chair, who decides whether to allow involvement or manage the conflict in another way.

UNHCR colleagues assigned to the MFT user role on the UNPP can check the profiles of organizations on the platform and use some of its information for technical evaluation.

The results manager provides the IPMC with an overview of the top-performing organizations based on their technical scores.

Partner screening

The IPMC secretary screens the UNPP for either the highest technically scored organizations (1-3), in case of a competitive selection process, or all non-competitively proposed organizations to identify the following information:

- Has the organization’s profile been verified?

- Have any flags been raised by a UN organization concerning the partner?

- Does the UNPP contain the results of any valid capacity assessments of the organization by UNHCR or other UN entities that may include relevant information against the selection criteria?

- Does the organization have a UN/UNHCR project audit internal control questionnaire (ICQ) or a UNHCR internal control assessment (ICA) risk rating available in the last three years?

The IPMC secretary shares the shortlist of screened organizations with the data protection focal point (DPFP) so that the DPFP can carry out the Data Protection and Information Security (DPIS) Initial Review of the Partner DPIS Self-Assessments. Risk levels for each individual control in the DPIS Initial Review form are automatically calculated based on the drop-down selections made by the partner in their DPIS self-assessment form. These risk levels are preliminary and indicative. They can be used to assist in shortlisting, but IPMC members are encouraged to review the information provided in the “Additional details” field of the form. The DPFP shares the results of the DPIS initial review with the IPMC for its consideration. See the External Guidance Note for UNHCR Funded Partners on Minimum Information Security Baseline for more information.

The IPMC secretary then presents the findings to the IPMC for its deliberation. Registration of a partner in the country of operation is not a pre-condition for selection but may be required by local legislation. Partners are responsible for securing government requirements for registration and operation in each country before the project workplan is signed. Therefore, at this initial stage, and dependent upon the country’s requirements, the IPMC secretary may also check the registration documentation of an organization.

Recommendation and decision

The IPMC secretary generates UNPP reports for the IPMC’s review, alongside the technical evaluation, which include the current status of organizations regarding a) the PSEA capacity assessment; b) the UN/UNHCR project audit internal control questionnaire and/or internal control assessment risk ratings; c) and the risks flagged.

Following the technical evaluation, the IPMC recommends to the head of sub-office, representative or director one or more organizations with whom UNHCR may enter into a partnership framework agreement (PFA), data protection agreement (DPA) and subsequent project workplan. The IPMC may recommend to pool or roster multiple partners for specific results or sectors.

The recommendation includes further requirements and documentation (e.g., reference check, web search etc.), and notes whether any further capacity assessments are required, which include verifying the completeness and validity of the organization’s PSEA assessment and the development of a capacity strengthening implementation plan (CSIP) if required, as well as conducting a data protection and information security capacity assessment. The IPMC may provide observations about a recommended partner that is to be considered during the project design. The head of sub-office, representative or director can agree or disagree with the IPMC recommendation and has the option to select another partner or undertake a new selection process. A justification for the decision is documented on the operation’s SharePoint.

💡 KEEP IN MIND The IPMC notes areas of weakness or potential improvement that do not preclude the organization from being the best-fit partner. These recommendations could be included in the project workplan risk register and are addressed during implementation. For example, the IPMC may make observations about an organization’s capacity to absorb additional funding in the event of an emergency or other circumstances resulting in an OL increase. |

Partner notification

To demonstrate transparency, programme personnel inform all applicant organizations about the outcome of the selection process in a timely manner. This is normally communicated automatically via the UNPP.

The selected partner’s name may or may not be announced to all organizations at the operation’s discretion. The operation communicates with applicant organizations using appropriate methods considering protection sensitivities, security constraints, and the operational environment (e.g., UNPP, email, letter etc.).

Partners requesting clarification on selection decisions receive a response from the head of sub-office, representative or director, explaining the transparency and integrity of the process, within fifteen working days after the finalization of the CfEoI. In exceptional cases where operational sensitivities prevent disclosure, the partner is informed that no feedback can be provided. Dissatisfied organizations may escalate their concerns to UNHCR via [email protected], in which case the bureau reviews the process undertaken by the country operation. The dissatisfied organization is informed as to whether fairness and adherence to the procedure were observed.

The closure of the partnership selection process triggers the commencement of the capacity assessments, as required. Any exceptions or delays in partnership selection are documented, such as late notification of the partnership selection outcome due to new outputs and activities or earmarked funds.

Partnership selection recordkeeping

Programme is responsible for keeping records and documentation of the selected partner. All legally binding contractual documents are stored in the “Contracts” module of Cloud ERP. For processes not documented in the UNPP or the Project, Reporting, Oversight and Monitoring Solution (PROMS), the operation’s SharePoint is used to retain records for six years following project completion. Documentation for recordkeeping includes the partner’s registration, self-declaration, and verifications of post-sanctions screening, the CfEoI, the partner’s PSEA capacity self-assessment (only in case the offline template is exceptionally used), the partner’s data protection and information security capacity assessment, concept notes, technical evaluation matrixes or scoring, the partner’s feedback on the selection process, the minutes of the IPMC and their recommendations, and any alternative decisions made by the representative.

After the IPMC recommends a partner, its capacity may need to be assessed. These assessments influence whether UNHCR signs a data protection agreement (DPA) and project workplan with a partner and how much responsibility is placed on the partner. UNHCR is transparent with partners when assessments are conducted and opportunities to improve are identified.

UNHCR expects that partners are on their own journey to reform, improve and grow, and it supports them in these efforts. Except for PSEA, and data protection and information security (DPIS), UNHCR does not dictate what capacity a partner needs to strengthen, rather the partner determines its own reform priorities and learning agenda.

Partners, including governments, can make a request to UNHCR for capacity-strengthening funds. This capacity-development initiative can be documented as an output under a project workplan. For small organizations led by forcibly displaced or stateless people, UNHCR has a grant mechanism (see grant agreements below) with minimal requirements that can be used by organizations led by forcibly displaced and stateless people to strengthen their capacity.

The most senior programme colleague coordinates all capacity assessments required by the partner, ensuring that the MFT members lead assessments in their area of expertise.

All recommended actions for improvement are followed up throughout implementation, and any documented improvements are captured during the project performance verification process and recorded in PROMS.

💡 KEEP IN MIND

|

Partner’s capacity to protect from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA)

Overview of PSEA

UNHCR is committed to the IASC Six Core Principles and the Secretary-General’s Bulletin: Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse, to ensure the protection from sexual exploitation and abuse of affected communities. Ensuring that these principles and measures are assessed under a partner’s PSEA capacity and putting in place a plan to address any identified gaps, is a prerequisite for a partnership with UNHCR.

When entering agreements with partners who work in direct contact with forcibly displaced and stateless people, operations ensure that the partners have a valid PSEA capacity assessment. The PSEA capacity assessment tool currently applies only to NGOs.

Several UN organizations (including UNHCR) have agreed on a common partner PSEA capacity assessment tool based on eight core standards, effecting the requirements of the United Nations Protocol on Allegations of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Involving Implementing Partners (the UN Protocol). This common tool is digitized and available in the “PSEA” module of the UNPP. It enables UN organizations to assess the partners’ PSEA capacities in accordance with the UN Protocol. Where needed, the UN organizations, together with the partners, develop and monitor a capacity-strengthening implementation plan (CSIP) based on the gaps identified.

Partner assessments conducted by one UN organization using the common tool are recognized by the others. This avoids the duplication of assessments of common UN partners and maintains information-sharing and transparency between the UN organizations and partners. In exceptional cases, if a partner has no access to the UNPP, the assessment is conducted offline using the template available and shared with UNHCR via email. See the Inter-agency PSEA Implementing Partner Protocol Resource Package on the UNPP for further guidance and the offline template of the tool.

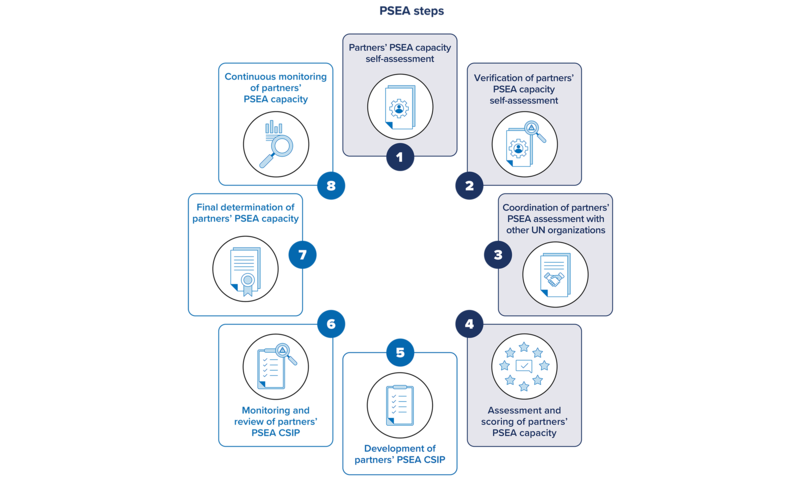

The key steps for the PSEA capacity assessment of a partner are:

- Partners’ PSEA capacity self-assessment.

- Verification of partners’ PSEA capacity self-assessment.

- Coordination of partners’ PSEA assessment with other UN organizations.

- Assessment and scoring of partners’ PSEA capacity.

- Development of partners’ PSEA CSIP. See GET – Section 2.

- Monitoring and review of partners’ PSEA CSIP. See GET – Section 4.

- Final determination of partners’ PSEA capacity. See GET – Section 4.

- Continuous monitoring of partners’ PSEA capacity. See GET – Section 4.

Partners’ PSEA capacity self-assessment

Relevant organizations complete a PSEA capacity self-assessment in the “PSEA” module of the UNPP and upload the supporting documents. If UNHCR’s project does not require an organization to have direct contact with forcibly displaced and stateless people, the organization indicates that in their self-assessment. It is not mandatory for that organization to complete the self-assessment, though the option is available.

If the partner has been assessed by a UN organization using the common tool within the last five years, there is no need to redo the assessment. UNHCR reviews the assessment and supporting documents and may request any additional documents from the partner if missing. A new assessment is only needed in case of significant changes in the operational context or the partner’s structure. See GET – Section 4 for more details on reasons for reassessment.

Verification of partners’ PSEA capacity self-assessment

As part of the partner screening process, whether competitively selected or not, the IPMC secretary checks the UNPP for the organization’s PSEA capacity self-assessment. In cases where the organization applied offline, the PSEA self-assessment form and supporting documents will be submitted offline. This screening aims to verify the status of the PSEA capacity assessment of either the highest technically scored organizations (1-3) or the organizations proposed through a non-competitive process. This information is presented for the deliberation of the IPMC.

The following are considered during this process:

- Any flags raised on the UNPP about the organization’s PSEA capacity.

- If the organization has an existing assessment that is still valid (i.e., conducted within the past five years).

- If there is a need for a new assessment in case the existing assessment has expired.

- The availability of supporting documents.

- If the organization is ineligible due to not meeting Core Standard 8 on corrective actions. In that case, UNHCR cannot partner with this organization.

If a shortlisted partner has an existing assessment that was carried out more than five years ago, the IPMC secretary requests them to complete a new PSEA self-assessment as soon as possible in order to be considered shortlisted.

If the review of the partner’s supporting documents for Core Standard 8 does not give rise to justified doubts that a partner has taken adequate corrective measures following a previous SEA allegation, and if no flags exist on the partner’s UNPP profile, the operation may act on the assumption that the organization adheres to Core Standard 8.

SOFTWARE TIP: UNPP For further guidance on the partner’s self-assessment, see the PSEA Module User Guides and Resource Materials. |

The IPMC recommendation to the head of sub-office, representative or director notes the need for the completion of the PSEA assessment/scoring and the development of the CSIP (if required) before signing the project workplan.

Coordination of partners’ PSEA assessment with other UN organizations

At the country level, the relevant UN organizations agree on a lead agency to coordinate the PSEA assessments of common partners. Interagency PSEA coordinators at the country level have a role to play in the coordination of PSEA assessments of common partners. UNHCR usually takes the lead in refugee settings. If common partners are assessed at the same time, the UN agencies involved decide which of them will lead the assessment on a case-by-case basis, according to context-specific criteria such as the type of projects implemented and the financial size of the agreement.

Assessment and scoring of partners’ PSEA capacity

Once the IPMC recommends an organization for selection to the head of sub-office, representative or director, and if no valid capacity assessment is available, UNHCR assesses and scores the partner’s PSEA capacity self-assessment. This process is usually coordinated by the most senior protection function (PSEA focal point), or other designated PSEA focal point, who has the technical expertise to assess the potential partner’s adherence to the core standards and the relevant supporting documents. A multi-functional team (MFT), led by the senior protection officer or the PSEA focal point and comprised of IPMC or non-IPMC members (including programme and project control), according to the operation’s context and capacities, is designated to carry out the process of the PSEA capacity assessment of partners. The operation also grants the relevant team members access to the UNPP, according to their roles in the assessment process.

The designated MFT reviews the partner’s self-assessment to determine whether adequate safeguards are in place to prevent, mitigate and respond to the risks of sexual exploitation and abuse. Compliance with each core standard is assessed individually, by reviewing the relevant supporting documents, and rated with a “yes” or “no” (or “n/a” for Core Standards 2 and 8) and the score is calculated accordingly. If the offline template has to be used exceptionally, the head of sub-office, representative, director or a delegate (e.g., the chair of the IPMC) signs the preliminary determination or the final determination of the partner’s PSEA capacity.

The UNHCR assessment may require further communication with the partner and/or other UN organizations, for example in the case of common partners, if the assessments were previously carried out by another UN organization, or if there are any missing supporting documents. Knowledge of past allegations against partner personnel is disclosed with the understanding that details of individual cases remain confidential.

If the partner has an existing and valid assessment by another UN organization, UNHCR may review it, together with the supporting documents, and may request any additional supporting documents if required given the operational context of the planned project. A new assessment is recommended in case of a new emergency or significant changes in the operational context or the partner’s structure, or if the last assessment was carried out more than five years ago.

SOFTWARE TIP: UNPP For further guidance on assessing and scoring a partner’s self-assessment, see the PSEA Module User Guides and Resource Materials. |

The UN/UNHCR assessment may result in one of the following scenarios:

1. Full capacity (meets all 8 core standards)

The final determination of the PSEA capacity is concluded on the “PSEA” module and UNHCR’s regular partnership engagement procedures apply. It is valid for five years. UNHCR communicates the results directly to the partner if the offline assessment modality was exceptionally used.

2. Medium or low capacity (meets from 1–7 core standards)

A preliminary determination of the partner’s PSEA capacity is concluded. UNHCR may decide to proceed with establishing a project workplan with a partner with medium (six or seven core standards met) or low capacity (one to five core standards met). The operation needs to justify its decision, given the partner’s capacity gaps, on the “PSEA” module. This justification is visible to UN organizations participating in the UNPP, but not to the partner. The remaining gaps are addressed through the development of a capacity strengthening implementation plan (CSIP). See GET – Section 2.

Reasons for signing a project workplan with a low or medium-capacity partner may include their specialized technical expertise within a particular area, lack of viable alternatives in that sector or location or a satisfactory risk assessment of the partner. Capacity strengthening regarding PSEA is a key area of UNHCR’s work with these partners.

Operations that have assessed one or more partners as low capacity are encouraged to proactively identify potential alternative partners that could assume responsibility for areas of work performed to avoid the potential disruption of services to forcibly displaced and stateless people.

See a sample of communications with partners available in the Inter-Agency IP Protocol for PSEA of the Resource Library on the UNPP. More information on the assessment and scoring of partners’ capacity and the minimum requirements is available on the Interagency PSEA IP Protocol Resource Package for Partners.

Internal control assessment

When a partner recommended by the IPMC lacks a UN/UNHCR project audit internal control questionnaire (ICQ) or an internal control assessment (ICA) from the past three years, or the UN-conducted assessment does not follow the harmonized ICA/ICQ template, the MFT, led by project control, must complete an ICA. The ICA takes place as soon as the partner is selected and assesses whether they have sufficient internal controls in place to achieve the project’s desired results. If the ICA cannot be completed before the start date of implementation, ahead of the project workplan signature, the exceptional circumstances are signed by the head of sub-office, representative or director, documented and uploaded to the Aconex document register for audit purposes.

All funded partners, except UN and grant agreement partners, undergo the ICA to determine their internal control strength. Government partners are not exempt from the requirement of an ICA/Q. However, if operations encounter challenges when requesting government partners to review their policies and evidence of compliance during an ICA/Q, a high-risk rating will be applied by the operation when determining the essential controls for the project workplan.

The ICA examines the partner’s legal status, governance structures, financial viability, programme management, organizational structure and staffing, accounting policies, assets and inventory, financial reporting, monitoring, and procurement rules and capacity. The ICA focuses on compliance with policies, procedures, regulations and institutional arrangements issued both by the host government and the partner.

The ICA results in risk ratings of either low, medium, significant, or high in multiple areas of controls, providing the same categorized and overall risk rating for a partner as the ICQ conducted by UN project auditors. However, the ICA risk rating is superseded by a project audit ICQ risk rating. Hence, either an ICA or a UN/UNHCR project audit resulting in an ICQ takes place every three years for every UNHCR-funded partner.

💡 KEEP IN MIND The supply function leads in reviewing the procurement category within the ICA. This is a critical assessment within the overall ICA that informs the operation of the partner’s procurement rules and capacity and identifies the risks and opportunities. |

UNHCR ensures that partners have effective internal controls in place to track progress and safeguard the quality and timeliness of goods and services delivered. This helps to ensure that resources received from UNHCR are used in line with the project workplan and not diverted for other purposes. The ICA/Q helps UNHCR assess the risks associated with each partner organization, identify ways to mitigate these risks, and determine how to leverage the strengths and opportunities of the partners when relevant.

In situations where partners are not willing to share some information due to confidentiality or other concerns, UNHCR (for the ICA) or project auditors (for the ICQ) write directly into the concerned section of the ICA/Q that the partner is not able to disclose such information, including reasons if known.

Supporting documents, reviewed during the ICA process, include, for example, the policies, manuals, certificates of incorporation, organograms, and procurement-related documents such as standard operating procedures (SOPs). These documents, when reviewed during the ICA, are referenced as such within the ICA template. Where the partner’s processes are rated as moderate (medium), significant or high-risk, project control colleagues upload such supporting documents to the PROMS document register for audit purposes.

Partners are engaged in discussions on internal control improvements, identifying areas where UNHCR may provide support to strengthen their project management capacity (e.g., training and additional project funding). The results of the assessment assist in identifying the timing and nature of ongoing implementation monitoring and determining the types, timing, and extent of procedures applicable to subsequent project audits.

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: Aconex The ICA review process utilizes the “Document” and “Workflow” modules in Aconex. Click here for more details and here for the workaround process. |

The ICA, once completed by the MFT, is uploaded by project control on the UNPP. The Regional Controller monitors that country operations, within their bureau, are completing ICAs in a timely manner and to the quality required, in compliance with established guidelines.

💡 KEEP IN MIND The ICQ, once completed by auditors as part of scheduled audits, is uploaded directly into UNPP/IAM by the assigned project auditors. |

Leading on from the finalization of the ICA report, project control is responsible for consolidating identified ICA recommendations to improve the partner’s controls and for entering these recommendations into the UNPP IAM. The matrix of ICA recommendations is downloaded from the UNPP IAM and is shared with the partner in PROMS, ensuring all MFT members are involved in follow-up.

See the Offline Templates for the Internal Control Assessment (EN, FR, ES).

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: Aconex The ICA recommendations process utilizes the “Document” and “Workflow” modules in Aconex. Click here for more details and here for the workaround process. |

Partners’ procurement capacity

UNHCR aims to align its partner’s procurement rules, regulations and practices with the UN and UNHCR’s key procurement principles and ethical standards. All goods and services, except for medicines, core relief items and vehicles, may come under a project workplan’s financial plan when a medium or low procurement ICA/Q risk rating is concluded.

If the ICA results in a significant or high procurement ICA/Q risk rating, the IPMC shall consult with the supply function about how the procurement needs of the partnership can be met. The IPMC shall recommend to the head of sub-office, representative or director, the limitations to be applied to the project workplan regarding procurement. These limitations may include the partner’s ongoing operating procurement costs such as rent, communications, utilities, security, insurance, travel and partner affiliate workforce (see GET – Section 2 for the financial plan limitations). The final decision is made by the head of sub-office, representative or director, and is summarized within the project workplan risk assessment as additional factors considered when deciding essential controls. All factors considered for the decision surrounding whether such procurement limitations will be applied or not, including the size of the operation and the UNHCR supply unit, are documented through the head of sub-office, representative or director signing the project workplan.

All recommendations to improve and strengthen a partner’s procurement rules and capacity, as identified by an ICA, are incorporated in the ICA recommendations matrix. Procurement risks and opportunities identified during the ICA may also be jointly incorporated, alongside respective treatment plans, in the project workplan risk register (see GET – Section 2). Country operations continue to monitor the partner’s procurement capacity by following up on the ICA recommendations, scheduled financial verifications, and project audits, as applicable.

Government partners from World Trade Organization (WTO) member States, excluding observers, have procurement rules that are considered compatible with UN/UNHCR standards. Therefore, the ICA/Q process compares WTO member State government partner compliance with UN procurement standards without having to review policies or systems in place. If a government partner from a non-WTO member state is found unable to comply with UN/UNHCR procurement principles due to legal constraints, the operation documents the circumstances and seeks guidance from DESS/SMS, including explanations and justifications. DESS/SMS reviews such submissions on a case-by-case basis and provides advice accordingly.

Partner’s data protection and information security (DPIS) capacity

UNHCR pursues best practices in data protection and information security (DPIS) when processing personal data and aims to work in close collaboration with partners towards the same. UNHCR seeks to create an environment that enables the principled collection, use and sharing of personal data in furtherance of its mandate. Therefore, the same DPIS measures apply for funded partners as they do for direct implementation projects which involve the processing of personal data of forcibly displaced and stateless people.

When relevant to the partnership, each call for expression of interest posted on the UNPP by UNHCR requires partners to complete the template and specifies whether the respective project involves a Controller to Controller (C2C) or Controller to Processor (C2P) model with respect to the processing of personal data in connection with the activities to be performed.

- In a Controller-to-Controller (C2C) relationship, both parties accept equal responsibility for these areas. The C2C model is applicable for most projects involving case management (notably programmes focused on the delivery of health, protection case management, protection monitoring, GBV programming, child protection interventions, etc.). Hence both UNHCR data protection policies and partner and national policies apply.

- In a Controller-to-Processor (C2P) relationship, UNHCR assumes primary responsibility in these areas. The C2P model continues to be most appropriate for most other projects. The UNHCR data protection policy is the sole applicable framework.

The IPMC secretary shares the shortlist of screened organizations, with the highest technical score from the evaluation, with the data protection focal point (DPFP) so that the DPFP can carry out the initial review of the partner DPIS self-assessments. The results of the partner DPIS self-assessment are processed using a DPIS Initial Review form to gauge the indicative risk level for each applicant organization.

The DPFP shares the results of the DPIS initial review with the IPMC for their consideration. Risk levels for each individual control in the DPIS initial review are automatically calculated based on the selections made by the partner in their DPIS self-assessment. These risk levels are preliminary and indicative.

For partners recommended by the IPMC and for whom the DPIS initial review has already been completed, the DPFP, assisted by the cybersecurity focal point (or IT lead), conducts the DPIS Capacity Assessment.

The in-depth capacity assessment process includes measuring an indicative risk level (high, medium, or low) based on the DPFP’s DPIS initial review from the partner’s responses to their self-assessment, identifying appropriate mitigation measures in consultation with the partner and estimating the residual risk level that will be achieved by implementing them.

The assessment framework is focused on practical, testable controls that UNHCR can check and verify when visiting partner offices, as well as a contextual protection analysis. The assessment builds on top of the UN-wide risks assessed during the ICA/ICQ. The highest data protection risk(s) and information security risk(s), with their corresponding treatment plans/mitigation measures, are incorporated in the project workplan risk register, prior to the signature of the project workplan.

For directly selected partners, the partner still completes the partner DPIS self-assessment, before signing the DPA, and the DPIS capacity assessment is completed by the DPFP.

The DPIS capacity assessment remains valid for the duration for which the partner is selected.

Operations use global mandatory and protected templates that are approved by the Legal Affairs Service (LAS), accessed in Cloud ERP and signed to establish agreements. UNHCR uses standard agreement types for funded partnerships, which equate to a different contract template available in three languages (English, French and Spanish) and are available to download from the Cloud ERP “Contracts” module. Translating any template into another language will not be recognized as the official contract. The standard agreement types are set out below. While not all partnerships involve financial commitments from UNHCR, they are critical in achieving protection and solutions outcomes for forcibly displaced and stateless people.

The following table summarizes the standard types of partnership agreement templates available in Cloud ERP.

| Type of agreement | Type of organization | Timeframe | Level of application | Funding commitment |

| Global partnership agreement | International non-governmental organization (INGO) partners | Indefinite | Global | No funding commitment |

| Partnership framework agreement | All partners | Ideally multi-year | All levels | No funding commitment |

| Data protection agreement | All partners processing personal data of forcibly displaced and/or stateless people | Ideally multi-year | All levels | No funding commitment |

| Project workplan | All partners | Annual or shorter | All levels | Funding commitment |

| Grant agreement | Organization led by forcibly displaced or stateless people | Annual or shorter | All levels | Grant commitment |

| UN to UN agreement | All UN organizations | Annual or shorter | All levels | Funding commitment |

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: Aconex The content of all types of partnership agreement contracts can be negotiated and finalized with partners in Aconex utilizing the “Document” and “Workflow” modules. The final signed contracts are then uploaded to the Aconex document register. Click here for more details and here for the workaround process. |

💡 KEEP IN MIND Non-standard partnership agreements govern funding arrangements between UNHCR and the partner where exceptions to the established standard funded partnership agreement are required. These exceptions may arise due to the nature of the arrangement, counterpart entity and the funded activities. The non-standard partnership agreement incorporates special provisions agreed upon by LAS and the partner. The same partnership management principles that apply to a standard agreement also apply to a non-standard agreement unless otherwise stipulated. For further information contact your bureau. |

A global partnership agreement (GPA) may be established for international partnerships, often with INGOs, at a global scale. The GPA is comprised of global partnership commitments that encompasses strategic partnership opportunities between UNHCR and a partner. It may include provisions that impact upon policies, procedures, and rules. Where a GPA involves changes to template documents, it will include an annexed non-standard PFA cover sheet template that sets out the special provisions agreed upon with the partner for global use and signature by UNHCR operations.

Upon completing the partnership selection process – whether competitive or otherwise – the operation can proceed with the multi-year partnership agreements. However, it is often advantageous for the operation to wait until any required capacity assessments are completed, allowing for alternative partnership options if the assessment results indicate that control measures may be insufficient for the intended results.

There are two types of standard multi-year partnership agreements, often aligned with the duration of the operation’s multi-year strategic plan, as follows:

- Partnership framework agreement (PFA)

- Data protection agreement (DPA)

Partner registration

A partner entering into a PFA and DPA is first registered in Cloud ERP. The operation sends a Cloud ERP Partner Registration Form to the partner to either complete its details and/or review and update information for verification.

An invitation is then sent to the partner to register in Aconex. After creating a profile in Aconex, the partner can collaborate and negotiate with UNHCR on a PFA and DPA (where relevant), and subsequently on the project workplan.

🤝 SOFTWARE TIP: Aconex The process of creating a profile in Aconex is outlined here. |

Partnership Framework Agreement (PFA)

A partnership framework agreement (PFA) includes two components, as follows:

- Standard partnership terms, which define the terms and conditions of the partnership between UNHCR, the partner and the government (in the case of tripartite agreements).

- A standard PFA cover sheet contract, which is available in Cloud ERP.

The PFA cover sheet contract is often over a multi-year duration, typically aligned with the operation’s strategic plan that lasts three to five years. The PFA describes the purpose and scope of the partnership for which the partner was selected and does not go beyond the Area of Budgetary Control (ABC). The PFA may be bipartite or tripartite, if the government also signs. It does not include any financial commitment. See an Example of a PFA Cover Sheet (EN, FR, ES) and the PFA Contract Presentation for guidance on how to fill out the contract.

Pooled bank accounts

The PFA cover sheet includes the type of bank account. Partners are required to nominate one bank account to which UNHCR will transfer prepayments for the project. They can use a pooled bank account without prior approval from UNHCR if they have adequate mechanisms in place to trace the use of UNHCR funds. The partners allow UNHCR and its project auditors to conduct financial verifications by accessing the pooled account bank statements and related reconciliations. However, if a partner is unable to satisfy these requirements, it is the partner’s responsibility to open a separate bank account exclusively for the use of UNHCR funds. This separate bank account ensures proper tracking and accountability of UNHCR funds.

If the partner plans to use both a pooled bank account and a dedicated one, they must have a clear policy on how exchange rates are managed for pooled expenses, and this policy should be made available to the UNHCR operation. The operation is then recommended to consult with their bureau for guidance before finalizing the PFA.

Misconduct disclosure procedures

The PFA cover sheet asks for the partner’s misconduct disclosure procedures, which links to their PSEA capacity assessment’s Core Standard 3 on vetting and reference checks for potential new hires. In case the operation is still verifying the PSEA capacity assessment, it can leave this blank and later amend the PFA, entering these details.

If PSEA capacity-strengthening is in process, a good option for partners is to consider joining the Misconduct Disclosure Scheme (MDS). Under the MDS, a partner is committed to systematically conducting reference checks for potential new hires and responding to such reference checks from other employers. Joining the MDS will support the partner in meeting the requirements of Core Standard 3. Therefore, the partner may stipulate that they have already joined the MDS or note their intention to join the MDS as soon as possible. That said, partners may also have other misconduct disclosure procedures in place, which they should then describe in this section of the PFA cover sheet.

A PFA can be signed with a partner even before capacity assessments are finalized. Within the PFA terms and conditions, the partner commits to undergo UNHCR capacity assessments as necessary. Depending on the risks identified and the subsequent results outlined in these capacity assessments, an operation may decide not to proceed with a project workplan and may, in exceptional circumstances, propose to the IPMC that the PFA be terminated on these grounds. All capacity assessments are concluded before a project workplan is signed and UNHCR disburses funds to the partner, except in the case of a declared emergency where special partnership procedures apply (see GET – Section 5).

Data Protection Agreement (DPA)

A data protection agreement (DPA) is subject to a PFA and is required whenever the partner is foreseen to process personal data of forcibly displaced and stateless people under the project workplan. A DPA is a legally binding document between UNHCR and a partner that establishes the terms and conditions of how the personal data of forcibly displaced and stateless people, who are benefiting from a project/service delivered/provided by the partner, will be used. A DPA signifies the principles and standards set out by UNHCR’s personal data protection and privacy framework established by the General Policy on Personal Data Protection and Privacy. A DPA often covers a multi-year duration, is aligned with the PFA and by itself does not impose any financial obligations.

The DPA includes standardized terms only and therefore requires the completion of the corresponding “Data Protection” table in the project workplan to outline the personal data processing particulars for the relevant project. This allows for specifying details relating to the processing of personal data such as the specific purposes, personal data elements, transfer methods, and additional safeguards.

The content and structure of the DPA are grounded in the principles of partnership and aim to reinforce mutual respect for the respective mandates, obligations, independence, constraints, and commitments of UNHCR and the organizations with which it partners. Moreover, the DPA recognizes that many of the organizations with which UNHCR collaborates have their own data protection and privacy policies and are also subject to compliance with data protection laws applicable in the jurisdictions where they work.

The DPA determines the roles and relationships of UNHCR and the partner, which is the foundation for correctly attributing the responsibility for the implementation of data protection principles and ensuring respect for data subject rights.

The DPA provides a foundation for clear, predictable, and principled data flows between UNHCR and its partners in compliance with key data protection and humanitarian principles.