GET - Section 5: Emergency Preparedness and Response

Overview

This section focuses on how UNHCR prepares and responds to emergencies. Preparedness and early engagement are fundamental for UNHCR to be a predictable lead and a reliable partner in a humanitarian crisis.

In a nutshell

- Operations conduct emergency risk analysis as part of the annual risk review and create contingency plan if there is a high risk of an emergency.

- UNHCR collaborates with partners and governments to align emergency preparedness and response efforts with the Refugee Coordination Model or the Inter-Agency Standing Committee structure.

- In declared emergencies, operations can access reserved emergency budgets, request supplementary budgets, and engage pooled fund mechanisms to address immediate needs, as well as seek additional workforce on the ground.

- In declared emergencies, special partnership management and supply procedures apply to facilitate rapid scale-up of response activities (e.g., waiver for competitive selection of partners).

- Robust monitoring systems track progress against emergency results while reporting mechanisms with CORE data products meet internal and external stakeholder needs.

- Post-emergency planning from the onset integrates emergency outcomes into regular operations, aligning strategies, structures and resources for long-term sustainability and accountability.

The Policy on Emergency Preparedness and Response provides the overall framework for UNHCR’s engagement in emergency preparedness and response at country, regional and headquarters levels. Detailed guidance on emergency preparedness and response is provided in the UNHCR Emergency Handbook.

UNHCR defines an “emergency” as any humanitarian crisis or disaster which either:

(i) has caused or threatens to cause new forced displacement, loss of life and/or other serious harm;

or

(ii) significantly affects the rights or well-being of refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), stateless people, returnees and other people with and for whom UNHCR works, unless immediate and appropriate action is taken;

and

(iii) demands exceptional measures because the current government and UNHCR capacities at country and/or regional levels are inadequate for a predictable and effective response.

In any humanitarian response, the primary objective is to save lives and minimize serious harm by meeting the most pressing humanitarian needs.

UNHCR declares internally one of three emergency levels, considering the expected magnitude, complexity and consequences of a humanitarian crisis compared to the existing capacity of the country operation(s) and bureau(x) concerned. The Policy on Emergency Preparedness and Response provides the definitions, timeframes and procedures for declaring a Level 1, Level 2 or Level 3 UNHCR emergency.

💡 KEEP IN MIND In situations of internal displacement, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) has a set of system-wide emergency activation procedures that are referred to as ‘SCALE-UP’. The IASC Humanitarian System-Wide Scale-Up Protocols comprise internal measures to enhance the humanitarian response, allowing IASC member organizations and partners to swiftly mobilize the necessary capacities and resources to respond to critical humanitarian needs. The special “scale-up” measures are applied for a period of up to six months, with an exceptional extension of another three months. |

UNHCR’s emergency preparedness and response are guided by the following key considerations:

- Embed humanitarian principles in all efforts.

- Respect and acknowledge the state’s responsibility.

- Reflect the centrality of protection.

- Integrate a solutions perspective from the start.

- Diversify and share roles with partners.

Emergency Risk Analysis

Regular proactive preparedness is essential for all UNHCR operations. This involves conducting an emergency risk analysis for new or escalated emergencies at least once a year as part of the annual risk review, in line with the Policy for Enterprise Risk Management. Through regular information gathering and analysis on the overall situation, protection monitoring, interactions with affected communities and dialogue at the inter-agency level in the United Nations Country Team (UNCT) or Humanitarian Country Team (HCT), a country operation evaluates the likelihood and potential impact of each agreed emergency scenario and ranks them as high, medium or low risk. The operation continuously monitors the identified emergency risks, updates the operational risk register and keeps the Division of Emergency, Security and Supply (DESS) informed of any high risks. An operation at high risk of a new or escalated emergency is included in the Emergency Risk Overview of the Emergency Preparedness and Response Portal, which is maintained by DESS in close coordination with the bureaux.

Country operations facing a high risk of a new or escalated emergency develop scenario-based contingency plans with government counterparts and partners. In a non-refugee context, the country operation aligns the UNHCR-specific contingency plan with the scenario collectively developed in the inter-agency coordination forum.

Contingency planning

Contingency plans include the planning scenario, population planning figures, activation triggers, coordination arrangements, response strategy, preparedness and response budget requirements, and workforce needs. Due diligence is paid to security, occupational health and safety, and other key institutional policies and guidance. As part of contingency planning, a country operation identifies key preparedness measures to be implemented to enable the planned emergency response. In addition, contingency planning considers the critical data and information required for emergency response, including registration and identity management.

The context-specific overall response strategy narrative in the contingency plan is used to outline the best achievable approach to ensure the adequate protection of forcibly displaced and stateless people. This narrative covers the general strategy considerations for issues such as, but not limited to:

- access to territory and asylum

- emergency registration

- needs assessments

- protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA)

- accountability to affected populations (AAP)

- prevention mitigation

- response to gender-based violence (GBV)

- information management support

- procurement and supply

- modalities of implementation (e.g., the distribution of non-food items directly by UNHCR or its partners)

- environmental sustainability and climate considerations

The strategy can be informed by the best available evidence and lessons drawn from previous emergency responses, notably from UNHCR evaluations and relevant inter-agency humanitarian evaluations.

Contingency plans include two main budget tables, one for UNHCR preparedness actions and the other for UNHCR emergency response activities (i.e. once the emergency has been declared). The two budgets represent UNHCR’s needs for emergency preparedness and response.

Budgets under contingency plans can be revised as the situation evolves. Importantly, budgets prepared as part of contingency plans have no impact on the operation’s current OP and OL.

It is important to update contingency plans regularly to align with the evolving context and to serve as the basis of emergency response plans and appeals such as a Refugee Response Plan (RRP) or to inform UNHCR’s contribution as cluster lead agency in a Flash Appeal or a Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (HNRP).

Registration and identity management

Delivering efficient protection and assistance in emergencies requires the registration of each household and individual, which helps in identifying beneficiaries, avoiding fraud and duplication, and managing assistance, including cash. Registration also facilitates referrals, case management and the issuance of documentation.

Setting up or scaling up registration capacity includes working in partnership with the government, other UN organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector to cover all requirements such as staffing, registration centres, ICT equipment, IT infrastructure, office equipment, transport, security, logistics and information campaigns. It is important for a country operation to develop a robust registration strategy that includes budgets and human resources requirements, as it is both time-consuming and costly to set up registration, and delays can directly impact the roll-out of assistance programmes.

Cash-based interventions (CBI)

Emergency preparedness for cash assistance is crucial to be able to initiate or scale up cash-based interventions (CBI) in an emergency. It is aligned to the guidance on financial management and related risks for cash-based interventions. Emergency preparedness includes:

- Cash feasibility assessments

- Preparing for cash delivery arrangements (including remote delivery and monitoring)

- Triggering early discussions on the possible use of the Global CBI Payments Hub

- Establishing partnerships (including a pre-selected pool of potential partners)

- Contracting financial service providers (FSP) to provide rapid CBI delivery

The country operation may need to consider extending existing contracts with financial service providers to ensure timely cash delivery. Furthermore, it is important to have clarity on the objectives of the cash-based intervention and to map out the estimated number of recipients, transfer values and potential targeting, ensuring coordination with the government’s social cash assistance and other cash actors in the inter-agency community.

Partnerships

At the time of the contingency planning, the existing partnership agreements and the stakeholder mapping are reviewed to identify potential gaps in expertise, considering the scope of required results, the target population, and the geographical place of delivery during an emergency.

While an existing project workplan would not be amended before the emergency declaration, a country operation may amend existing partnership framework agreements (PFAs) to allow for better preparation for the likely emergency. The Implementing Partnership Management Committee (IPMC) is required to make a recommendation for the amendment to a PFA where there is a change in scope to expand the partner’s geographical place of delivery and/or outcome areas for the required results. Any concerns surrounding the potential change in the scope of work and the subsequent impact on the partner’s capacity to deliver are discussed with the partner and addressed prior to signing any amendment to the PFA.

💡 KEEP IN MIND In non-emergency contexts, based on the recommendation of the IPMC, a head of sub-office, representative or director has the discretion not to release a call for expression of interest if:

and/or

|

If gaps are identified based on the stakeholder mapping, a country operation can establish a pool of potential partners as part of contingency planning. This allows for timely due diligence while ensuring that the best-fit partner is ready to embark upon an emergency response when required. This can entail:

- Expediting a call for expression of interest for a pool of potential partners, as a key preparedness measure to address the scope of projected activities and the geographical areas.

- Stipulating within the call for expression of interest the timeframe for which this pool of partners selected remains valid. For example, a country operation mobilizes potential partners from the pool until 20XX. If a pool of potential partners is recommended by the IPMC via a call for expression of interest, the UNHCR representative (or head of office) may sign an agreement with a partner from the selected pool during its validity period, whether or not an emergency of any level has been declared.

Workforce arrangements

The contingency plan specifies how the operation will identify, deploy and/or recruit the necessary human resources for all potential preparedness, response and coordination activities outlined in the plan. To do so, a country operation first maps the profile of its current workforce, including expertise, skills and work experience, relevant to the activities outlined in the plan. UNHCR may utilize its affiliate workforce and standby partnership agreements with government agencies, NGOs and the private sector whose specific expertise and capacity complement UNHCR’s internal emergency surge capacity, including the emergency technical and functional rosters.

It is important for the contingency plan to determine the frequency and approach of evaluating workforce needs, depending on the emergency level and how the situation is expected to evolve. For example, at the onset of an emergency, the staffing review may take place on a weekly basis, and a human resources cell can be established to ensure specialized support from the headquarters and the bureau. Avoiding or mitigating staffing gaps from the onset of an emergency enables the operation to sustain the planned level of activities in the post-emergency phase.

Inter-agency contingency planning in refugee situations

The UNHCR operation leads inter-agency risk analysis and contingency planning, jointly with the government, where possible, to ensure proactive anticipation, preparedness, and response coordination. The operation involves a range of key stakeholders from the onset of the risk analysis and scenario determination. Effective partnerships and coordination are central to a successful contingency planning process and ensure that roles and responsibilities are well-known in advance, creating a more collaborative approach, reducing duplications, and covering gaps. It is essential that UNHCR maintains direct contact with the host government, with a clear coordination structure established from the start.

The RCM guidance sets out the authority for UNHCR refugee inter-agency coordination and how this translates to UNHCR’s role in advocacy, response delivery, resource mobilization, broadening the support base, monitoring, reporting, and driving solutions.

The RCM looks at refugee coordination within the context of the Global Compact on Refugees and includes references to UNHCR’s catalytic role, “whole-of-society” approach, and the need to immediately engage line ministries to develop national arrangements, as well as development partners and other stakeholders at an early stage of the contingency planning to support an “inclusion and solutions from the start” approach.

Additionally, the RCM recognizes that inter-agency coordination arrangements are context-specific and notes that there are situations that call for a blended approach, such as working with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in the context of mixed movements or the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to advance the resilience of refugees and their hosts.

The UNHCR representative, as the main interlocutor with the government on refugee issues, maintains a strong and constructive relationship with the Resident Coordinator and/or the Humanitarian Coordinator and informs them of actions taken to prepare for a possible refugee influx.

A good way to kick-start the contingency planning process is to facilitate an inter-agency consultation and planning workshop, aimed at:

In the event of a situation that results in the forcible displacement of people across multiple countries, the country operations collaborate with the bureaux to coordinate their preparedness strategies and draw on any existing Regional Refugee Response Plans (RRPs), including relevant country plans. However, while regional consolidation is important, it is always secondary to the development of effective context-specific national and local preparedness plans. Each country in the affected region is likely to have different dynamics including, but not limited to, forms of government and institutions, operational partners, stances on the protection regime and institutional roles, and levels of assistance offered to arriving refugees.

Key aspects of preparedness useful at the regional level include:

- Prioritization of risks in the region

- Normalization of preparedness planning for refugee outflows

- Information-sharing to increase understanding of the risk of refugee outflows

- An efficient international response to emergency logistics needs

- Coordination of key messages, including protection

Inter-agency contingency planning in all other situations of forced displacement

While UNHCR leads inter-agency preparedness for refugee situations, for all other situations of forced displacement, including conflict, natural hazard-induced internal displacement, and mixed situations, UNHCR contributes to inter-agency contingency planning processes in the UN Country Team (UNCT)/Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) and fulfils its cluster leadership responsibilities in accordance with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) emergency response preparedness (ERP) approach.

UNHCR is the IASC-appointed cluster lead agency for protection, and in conflict-induced settings for shelter, and camp coordination and camp management (CCCM). The ERP approach includes the development of an inter-agency contingency plan once the UNCT/HCT identifies a specific moderate or high risk of an emergency. When the inter-agency process identifies the risk as high, but UNHCR assesses the risk as medium, UNHCR will still engage in the inter-agency contingency planning process as a member of the UNCT and/or HCT, leveraging UNHCR’s role as cluster lead agency.

The Humanitarian Coordinator or the Resident Coordinator leads the planning process for situations of internal displacement, usually supported by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). UNHCR leads and is accountable for the development of plans for the protection, shelter and CCCM clusters, as per the IASC cluster approach.

UNHCR aims to implement at least 25% of the overall inter-agency operational response under each cluster chapter in a humanitarian response plan (HRP) for internal displacement situations.

The contingency planning process is an ongoing activity and does not end with the completion of the plan. Regular review and updates occur, particularly when risk monitoring activities identify a change in the situation or when the institutional environment alters (e.g., if there is a significant change in membership or leadership of the UNCT/HCT).

💡 KEEP IN MIND Even in non-refugee situations, UNHCR is responsible for developing an internal agency-specific contingency plan. UNHCR will develop its agency-specific contingency plan in line with the goals and content of the inter-agency planning reflecting the agency-specific operational objectives and activities, including the risk scenario and its triggers/indicators, and related IASC ERP objectives and HNRP objectives (where an HNRP exists). If no inter-agency contingency plan has been developed or adopted, UNHCR will proactively undertake agency-specific contingency planning, with government counterparts and other agencies where the context permits. |

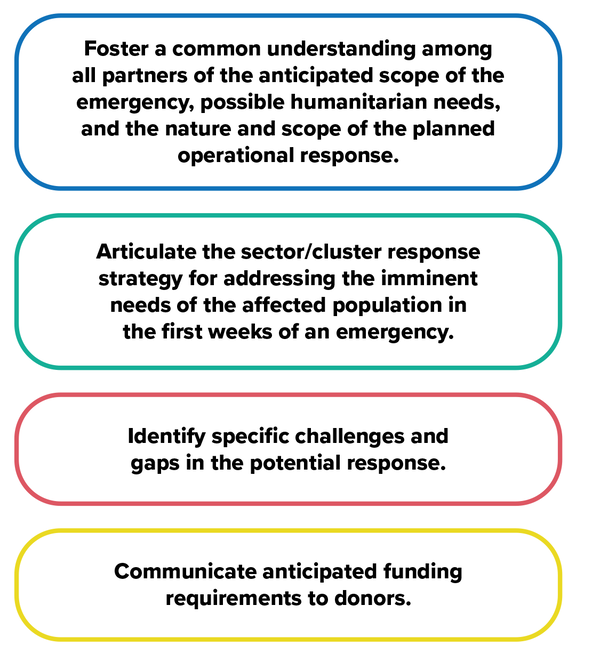

In all situations of forced displacement, the inter-agency contingency plan objectives are outlined below:

Assessments

In the first days of an emergency, it is important to gather key information as quickly as possible with an initial assessment to get an understanding of the situation. Start with a secondary data review and focus on key information that is critical to life-saving protection and assistance efforts and meeting emergency standards. Under the leadership of the representative and other senior colleagues, focus on information related to:

- Who is affected and where (number and profile of displaced people, geographic areas)?

- What are the most critical and immediate risks and needs (e.g., refugees, host communities)?

- Updating the context and who is doing what (e.g., government response, actors on the ground, possible partners).

The initial assessment can use rapid primary data collection methods alongside secondary data, such as observations, satellite imagery and interviews with different key informants (community members, authorities, key service providers, and local organizations). This initial assessment can be followed by a rapid assessment (within two to four weeks of an emergency) to gather more in-depth information and inform updates of appeals and priorities.

Responsibility for these assessments varies depending on the operation's structure and the type of assessment being conducted. However, sector or cluster leads are generally responsible for coordinating relevant sector- or cluster-specific questions and ensuring that their areas of expertise are adequately covered in the assessment.

The Needs assessment in refugee emergencies (NARE) is UNHCR’s multi-sectoral rapid needs assessment tool, designed to obtain an initial understanding of the needs. It applies several methodologies to produce a rapid cross-sectoral analysis of needs in an emergency. These first assessment efforts can already be captured in basic infographics through CORE tools, and expanded throughout the response. The NARE provides evidence to identify priority areas, groups and needs to respond to in an emergency, and is led by UNHCR in close collaboration with other agencies and partners. While the NARE is primarily designed for refugee emergencies, it can also be adapted for use in IDP and mixed situations.

When a sudden onset disaster strikes, a joint needs assessment process, the Multi-Sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA), is one of the first steps in the HCT’s emergency response and is usually led by OCHA. This process enables actors to reach from the outset a common understanding of the situation and its likely evolution. Based on its findings, humanitarian actors can develop a joint plan, mobilize resources, and monitor the situation. It is most effective in a sudden onset natural disaster but can be adapted for other emergency situations.

Results framework

The Emergency Handbook provides information on how to plan, implement, and monitor an emergency response using UNHCR’s programme cycle.

In order to ensure the delivery of appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance to affected communities and to allow for the rapid transfer of an OL (and potentially OP) increase, a country operation’s existing results framework can be modified at the onset of an emergency.

An operation uses existing results chains and makes changes:

- At the output level: The country operation can add new and/or revise existing output statements and/or add new output indicators, including new population types in the output statement.

- At the outcome level in consultation with the bureau: The country operation can add new and/or revise existing outcome areas, and statements and/or add new indicators, including new population types in the outcome statement. For new or revised outcome areas, corresponding output statements need to be added/revised, and indicators added.

- Creation of a new impact statement and results chain: This may only be done in very exceptional circumstances when the modification of the existing results framework is not feasible because the current impact statements in no way reflect the changes required in the lives of the affected populations targeted in the emergency response.

When adding a new outcome and/or output indicator, an operation:

- Defines the population type(s) and disaggregation levels for each indicator.

- Establishes baselines/targets where relevant for the indicator type.

- Identifies appropriate means of verification.

An operation is encouraged to choose a limited number of indicators with clear measurement criteria, a monitoring plan, and data collection mechanisms. If an indicator cannot be measured, it is not selected.

This approach helps a country operation avoid unnecessary complexity in the strategy’s narratives and facilitates the integration of activities into regular programming post-emergency.

💡 KEEP IN MIND If the emergency occurs in a UNHCR country operation with no current results chain, the creation of an entire new results framework is necessary. In this case, the operation first creates an area of budgetary control and a strategy in COMPASS before reaching out to the bureau for guidance on how to create new results chains. |

The results chains for country operations with a declared emergency are best kept simple, focusing on the key results the operation expects to achieve in the emergency phase and having only a limited number of new outcomes, outputs, and indicators. This simplifies budgeting, resource allocation, including requests for additional resources, partnership agreements, monitoring and reporting. There is always the opportunity to add later new outcomes, outputs and indicators (post-emergency).

In declared emergencies, the representative or director has the authority to decide on the best-fit implementation modalities without an IPMC recommendation. This decision considers the needs, operational capacity, presence and availability of other stakeholders, and other context-specific parameters. It must be documented. After the emergency declaration expires, the representative will revisit implementation modalities with the IPMC prior to the next year of implementation. The Emergency Handbook contains a Partnership Management for Emergency Preparedness and Response entry for further information. In addition, the Risk Management Tool for Funded Partnerships helps colleagues identify common risks and opportunities for partnership agreements in emergencies.

Once an emergency of any level has been declared, the following partnership management procedures apply for the duration of the declaration, including any extensions:

- The head of sub-office, representative or director can expand the scope of an existing partnership framework agreement (PFA) via an amendment (e.g., to cover a new outcome or geographical area) without a new recommendation from the IPMC, if the partner has prior experience, proven capacity and is willing to expand. The exceptional circumstances are documented in the operation’s SharePoint and signed by the head of sub-office, representative or director.

- The representative holds the authority to temporarily suspend competitive selection for new partnership agreements established within the emergency period. This decision must be documented. The operation must revisit implementation modalities with the IPMC after the emergency declaration period and prior to the next year of implementation.

- Any new partner must be registered on Cloud ERP, including bank account details.

- The registration, due diligence and verification on the UN Partner Portal for newly selected partners must be completed as soon as possible and no later than three months after signing the project workplan.

- All new partners’ PSEA capacity is assessed, and a capacity strengthening implementation plan (CSIP) is developed in case of low or medium capacity, as soon as possible and no later than three months after signing a project workplan in an emergency, in case of no existing valid assessment. See PLAN – Section 8 for more details on partners’ PSEA capacity.

- For new partners, operations generate, sign, and approve a standard PFA cover sheet, data protection agreement (DPA), if applicable, and a project workplan with basic information completed in Cloud ERP. A financial plan must be negotiated and documented in Aconex. The financial plan can be concluded on the basis of one account code (budget line) per output.

When the project’s implementation ends within the declaration period (including any extensions), it can be closed based on a PFA (and DPA if applicable) with project workplan minimum details and a financial plan. The project workplan’s liquidation, closure and audit can occur after the expiry of the emergency declaration.

- The creation and signature of a project workplan in an emergency can take place at any time of the year.

- If the project workplan is extended beyond the emergency declaration period, where an internal control assessment (ICA)/internal control questionnaire (ICQ) and/or data protection information security (DPIS) capacity assessment are required, the ICA and/or DPIS capacity assessment are to be completed before the emergency declaration expires. See PLAN – Section 8 for further details surrounding a partner’s capacity strengthening and risk management, as well as the applicable capacity assessment processes.

- To extend a partnership agreement established during an emergency beyond the emergency declaration period (including any extensions), an amendment to the PFA, DPA (if applicable) and project workplan is required. Extensions are only valid until the representative re-visits implementation modalities with the IPMC prior to the next year of implementation. The amendment is made to include all project workplan details, a results plan and a risk register, and requires the completion of a funded partnership agreement quality assurance checklist.

Monitoring is a crucial component of an emergency response. There are no reduced implementation and results monitoring requirements during an emergency. The frequency of monitoring activities may in fact increase.

To ensure effective monitoring, it is recommended that a country operation updates (or develops) the assessment, monitoring and evaluation workplan (AME), which is informed by the overall M&E plan. This will enable the operation to determine the key M&E activities required for the emergency. See PLAN – Section 6 for more information.

The humanitarian situation in a country is often fluid and subject to frequent change. Monitoring partnership projects is therefore essential to track and confirm their progress against agreed performance targets, adjust their direction and implementation as needed, and identify measures to improve their impact and quality. UNHCR, its partners and other stakeholders, including local authorities (as applicable), jointly monitor and review partnership projects, share information and coordinate to strengthen their collective ownership and joint responsibility for project results.

During an emergency, the MFT and the PSEA focal point regularly monitor the partners’ capacity to prevent, mitigate and respond to risks of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA). For a partner who is in a high-risk environment and has previously been assessed as having a low or medium PSEA capacity and therefore has a capacity strengthening implementation plan (CSIP) in place, the operation monitors the implementation of CSIP activities after three months from its development and continues checking its progress throughout the CSIP period, and the emergency declaration and any extension period. Within six months, or nine in the case of an extension to the CSIP, the partner should have reached full capacity. Reasons for signing a project workplan with a partner despite its low or medium PSEA capacity during an emergency need to be documented and may include the partner’s specialized technical expertise within a particular area, lack of viable alternatives in that sector or location, or a satisfactory risk assessment of the partner. See GET – Section 2 for more details about the development of a CSIP.