PLAN - Section 4: Vision, Strategic Priorities and the Theory of Change

Overview

The vision, strategic priorities and theory of change are established at the beginning of the PLAN for Results phase, based on a well-developed situation analysis and planning scenario. This helps operations formulate the positive changes they aim to achieve, identify the critical protection issues faced by forcibly displaced and stateless people and articulate how they will tackle these issues.

In a nutshell

- The vision is the guiding compass of a multi-year strategy. It describes the desired future situation of forcibly displaced and stateless people and shapes the strategy. It is different from a mission or impact statement.

- Identifying key strategic priorities based on the situation analysis and focusing on key issues and problems forcibly displaced and stateless people face is crucial for creating a clear and coherent theory of change.

- The theory of change is the basis of the results framework, which focuses specifically on what UNHCR can address.

- An operation’s multi-functional team (MFT) develops together the vision, strategic priorities and theory of change. It may involve external stakeholders, including UN organizations and representatives of forcibly displaced and stateless people, as needed, since engaging stakeholders is a key principle for UNHCR’s planning. To ensure an inclusive process, it is important to conduct a thorough stakeholder analysis in advance.

The vision, strategic priorities and theory of change are established at the beginning of the PLAN for results phase, based on a well-developed situation analysis and planning scenario. They set the direction and scope of UNHCR’s strategy and guide the involvement of other stakeholders.

The vision is a high-level statement of the positive changes UNHCR aims to contribute to, whether in a single country (for country operations), multiple countries (for multi-country offices), or across regions, and thematic areas (for bureaux, and headquarters divisions and entities). It serves as the foundation for setting strategic priorities and developing the theory of change. The vision is rooted in key assumptions from the planning scenario.

The strategic priorities are overarching issues in protection and solutions for forcibly displaced and stateless people. They are essential for accomplishing the vision and shaping UNHCR’s strategy and decision-making, informed by a detailed protection and solutions analysis.

The theory of change is a tool to identify how to achieve these strategic priorities through a series of changes, breaking down the vision into actionable steps.

It is important to incorporate age, gender and diversity considerations in the vision, strategic priorities and theory of change.

The development of the vision and strategic priorities starts a year before the current strategy ends (i.e., in 2024 if the strategy ends in December 2025). In country operations, this begins when the situation analysis is well advanced and operations consider lessons from the previous year, which are captured in the Strategic Moment of Reflection, the Annual Result Reports, evaluations, and other sources. It is important not to simply copy or slightly modify the previous vision, strategic priorities and theory of change. Instead, the operation uses available evidence, and the results of the Strategic Moment of Reflection, and starts a new thinking process. This ensures that the new strategy is relevant and responsive to current needs and challenges.

💡 KEEP IN MIND When determining the strategy's duration, it is important to consider the sustainable responses and route-based approaches and examine closely the results of the protection and solutions analysis. Operations may coordinate their strategy with other operations' strategies at the regional or sub-regional levels as needed. Setting the vision, strategic priorities and theory of change requires careful examination of UNHCR’s role shifting from implementer to catalyst. (see also PLAN – Section 3). |

Considerations for age, gender and diversity (AGD) in the vision, strategic priorities and theory of change

|

All operations formulate a vision to anchor their strategy.

What is the vision?

The vision outlines the overarching goals for protection and solutions for forcibly displaced and stateless people. It is formulated as a short statement that describes how the situation of forcibly displaced and stateless people will be transformed through the involvement of UNHCR, its partners and other stakeholders.

What question does a vision answer?

❓ What will the future look like for forcibly displaced and stateless people once their protection needs and solutions are addressed?

It is rooted in the planning scenario and informed by evidence from the situation analysis, results achieved, lessons learned from previous strategies and consultations with forcibly displaced and stateless people of diverse age, gender and other characteristics, as well as other stakeholders such as government authorities and UN organizations.

An operation can set a vision that extends beyond the multi-year strategy, recognizing that structural changes often take longer. The vision should align with the priorities of the new strategy but does not need to detail how to achieve them, as this is addressed in the theory of change.

Who is involved?

The representative leads the creation of the vision, supported by the senior management of the operation, the planning coordinator, and the multi-functional team (MFT). It is important to foster strong ownership of the vision among the team early in the process to ensure it effectively guides strategic planning and implementation.

What does it align with?

The vision of a UNHCR strategy aligns with the UNHCR Strategic Directions 2022-2026, the focus area strategic plans, and the objectives of the Global Compact on Refugees. It also aligns with national plans relevant to forcibly displaced and stateless people, such as government-led national development planning processes, and UN planning frameworks including the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF), Humanitarian Response Plans (HRPs) and Refugee Response Plans (RRPs).

Examples of vision statements

The UN Uganda Vision for 2030:

❝A transformed and inclusive Ugandan society where people have improved quality of life and resilience for sustainable development.❞

Sample vision statements:

- Forcibly displaced and stateless people have their rights protected, are able to participate in society and find opportunities for self-reliance and durable solutions.

- ❝By 2029, forcibly displaced and stateless people in the country are better protected and have full inclusive access to quality basic and protection services as well as economic opportunities on par with nationals provided by the government of the country.❞

- Increasing proportions of forcibly displaced and stateless persons belong to self-reliant, empowered and resilient communities, and are able to actively participate in, and benefit from, all aspects of their protection and durable solutions.

💡 TIPS

|

Strategic priorities form the foundation of the theory of change (see below) and become the impact statements that guide the strategy.

The MFT identifies up to five strategic priorities critical to the vision, which are directly relevant to UNHCR’s role and mandate and leverage the organization’s expertise and comparative advantage. It also considers the complementarity with national institutions and other stakeholders, ensuring a collaborative approach, and incorporates lessons learned from previous strategies.

Developing strategic priorities usually requires several rounds of discussion. The operations consider the main challenges and gaps identified in the situation analysis, the outcome of the commitments made by government, development actors and other stakeholders, specifically in the protection and solution analysis. This ensures that the strategic priorities address the key areas of change that make a real difference to the lives, well-being and overall realization of rights of forcibly displaced and stateless people.

When are the strategic priorities identified?

It is best to identify these priorities while setting the vision and before developing the theory of change.

What questions do you ask to identify your strategic priorities?

❓ What are the priority issues that UNHCR and others need to tackle to progressively move towards the vision?

To answer this question, operations consider the following criteria and guiding questions:

| Criticality |

|

| Mandate |

|

| Position |

|

| Capacity |

|

| Opportunities |

|

| Lessons Learned |

|

💡 KEEP IN MIND Operations may ask the following additional questions for the sustainable response and route-based approaches.

|

💡 KEEP IN MIND Global priorities, policies and strategies, including the focus area strategic plans, inform the identification of strategic priorities (see: Protection and Solutions for Internally Displaced People 2024-2030). |

Examples of strategic priorities

By the end of the strategy period:

- Refugees and asylum-seekers in the country enjoy a favourable protection environment with safe access to territory, official documentation, and, for some, residency.

- Refugees, especially women and children, benefit from inclusive national policies and protection-sensitive services, particularly those related to gender-based violence, health, and education.

- Refugees take part in the cultural, social and economic life of host communities, finding climate-resilient livelihoods and economic opportunities.

- Refugees have opportunities for safe and voluntary return and resettlement.

Joint review of strategic priorities

Conducting a joint review with partners and relevant stakeholders, including representatives of forcibly displaced and stateless communities, can help validate the strategic priorities. A joint review can build consensus on the key issues faced by forcibly displaced and stateless people and accelerate stakeholder support for national priorities that advance protection and solutions. It is informed by data and evidence, including the results from the Strategic Moment of Reflection, and is locally defined and shaped through discussions and workshops. This flexible and comprehensive approach ensures the effective setting and refining of strategic priorities.

💡 KEEP IN MIND Check your strategic priorities against these questions:

|

💡 TIPS

|

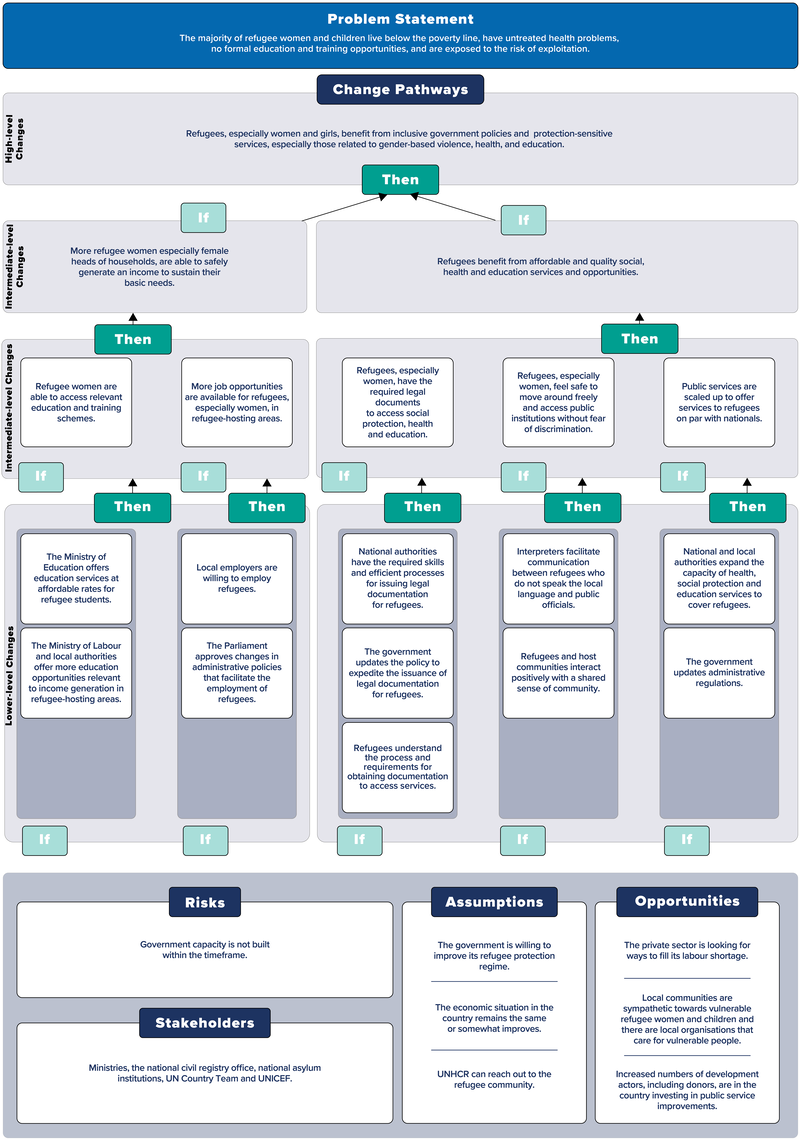

Once the strategic vision is set and the priorities are identified, the operations develop the theory of change. The theory of change is built for each strategic priority and defines what changes are required to address the strategic priorities and how to achieve them, laying the basis for the results framework.

Developing the theory of change is mandatory for country operations and multi-country offices and is strongly encouraged for bureaux and headquarters divisions and entities.

What is the theory of change?

The theory of change is a strategic planning tool that analyses problems and their causes and establishes how change can happen to achieve the vision (change pathway). The theory of change is summarized in a write-up and a visual graph in COMPASS.

Which questions does the theory of change answer?

The theory of change articulates the “if we want to change ‘x’, who needs to change what to achieve this change?”, rather than “if more resources are available, then partners will do ‘x’”.

It answers the questions:

❓ What are the underlying causes of each strategic priority issue?

❓ What needs to change to resolve the issue – and how, by whom, and by when?

❓ What are the risks, opportunities, and assumptions involved?

💡 KEEP IN MIND Operationalizing the sustainable response and route-base approaches: Operations may additionally ask:

|

Who is involved in developing a theory of change?

The development of a theory of change is a consultative and participatory process. It involves MFT discussions led by the planning coordinator, with strong leadership and direction from the representative.

Involving stakeholders (including government and partners) in the theory of change process is crucial for fostering an understanding of what UNHCR plans to do in collaboration with them and validates the logic of the theory of change. Their contributions can have a profound impact on the desired change and can inform UNHCR’s prioritization.

Engagement with forcibly displaced and stateless communities could involve dedicated consultation, participation during planning workshops and communication on planning outcomes and strategic priorities.

The format and timing of the stakeholder engagement are tailored to the specific context of each operation.

How to organize a theory of change development?

It is a good practice for the MFT to plan a series of meetings and workshops to collaboratively develop the theory of change.

In the theory of change process, operations articulate their assumptions, risks and opportunities. These elements form part of the risk management narrative (see PLAN – Section 7).

Developing a theory of change is not a linear process and the changes and assumptions identified may need to be revisited and adjusted multiple times as new insights and information emerge.

How can the theory of change relate to thematic areas and interagency work?

Operations can also develop a theory of change for specific thematic areas or population types, such as stateless people when they have very distinct needs and risks. In this case, it is important to bring these different theories of change together under one broader theory of change for a strategic priority. This comprehensive approach will then serve as the basis for the impact statement and the results framework.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) in the country or other relevant planning frameworks may also include a theory of change. Operations are encouraged to review and build upon these existing frameworks where relevant.

What are the steps to develop a theory of change?

Step 1: Conduct a problem-cause analysis

The theory of change is most useful when it provides a comprehensive picture of how change happens. To achieve this, operations conduct a problem-cause analysis for each strategic priority to fully understand its major causes.

The purpose of conducting a problem-cause analysis is to analyse the strategic priorities and understand the reasons behind each problem. This analysis is necessary to determine the high-, medium- and low-level changes needed to address the challenges and problems.

To understand the key problems and their causes, it is best to:

1. Formulate a clear problem statement for each strategic priority. The problem statement can focus on rights and needs not fulfilled, considering the systems, behaviours and attitudes of people and institutions.

The problem statement should speak to the gaps and challenges identified in the situation analysis, specifying who (e.g., the government, civil service, community, people) and what (e.g., systems and institutional arrangements, legal frameworks) is causing a problem, and in what way forcibly displaced and stateless people of all age, gender and diverse characteristics are affected.

| Strong problem statements | Weak problem statement |

| 60,000 refugees and 6,000 stateless people (over 60% of whom are women and children) do not have their health issues addressed and left on their own to cope with them. | Health services are not used. |

| Internally displaced children (especially unaccompanied boys aged 8-16, and all girls) are not in education, exposed to exploitation and are left with little prospects for the future. | Children lack access to services. |

2. Identify the causes of each problem. A problem can have several causes, and several causes may lead to the same problem. For each problem, ask why this problem exists, and continue asking “why and why again”, to dig deeper into the cause, considering:

- Which causes (e.g., values, attitudes, behaviours, capacity, structures/systems) need to be changed or transformed?

- What are the age, gender, and diversity dimensions of these causes?

- Who can act as an agent of change and have a substantive positive influence (including the forcibly displaced and stateless communities themselves based on their capacities and skills)? Can these agents change/transform the problems for the better?

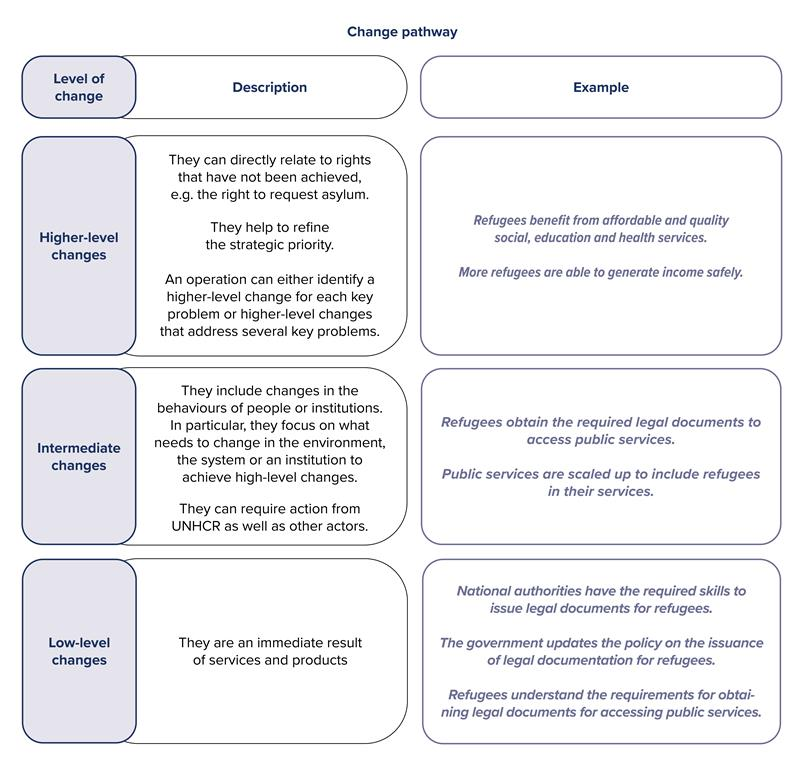

Step 2: Identify the change pathways

Change pathways define a series of forward-looking changes that address the problems and causes. For each strategic priority, the operation maps out the different levels of change that are necessary to achieve the desired impact, underpinning different strategic priorities. This is done using the if/then logic: If/when “scenario X” happens, then “Y” will change positively.

In this step, operations reflect on all the different changes needed to achieve the strategic priority, as guided by the vision. The focus is not on identifying “SMART results”. Instead, when developing the results framework, the changes are translated into impacts, outcomes, and outputs. Initially, the theory of change may consider overarching changes related to outcomes, which will later be followed by specific outputs relevant to UNHCR’s interventions.

Operations analyse the relation of the changes to:

a. The enabling environment, which includes legal and policy frameworks, national institution set-ups or other enabling systematic changes.

b. The provision of protection and solutions, which focuses on the availability of institutions providing adequate services, and equitable access, capacity, knowledge and attitude of staff in national and public institutions, as well as civil society service providers.

c. The behaviour and capability of stakeholders, such as authorities, civil servants, local community and forcibly displaced and stateless people, for example, their capacity to speak the local language, pay for services, and their cultural beliefs and behaviours.

Step 3: Undertake stakeholder analysis and identify UNHCR’s engagement

Building on the stakeholder mapping undertaken in the situation analysis, operations identify the changes that UNHCR is best placed to contribute to and changes that other stakeholders can achieve. This step informs the operation’s partnership and stakeholder engagement and allows UNHCR to further refine its role and contribution. This will shape the next step of developing the results framework for the coming years.

To undertake the stakeholder analysis:

- Identify the changes UNHCR must engage in based on its comparative advantage and mandate, as well as the criticality of the changes and the changes at different levels.

- Identify changes that other stakeholders (including communities of forcibly displaced and stateless people) can take action and influence, as well as existing and potential stakeholders for these changes. Understand their mandate and characteristics, including planning and operational modalities, communities targeted with their programmes, and their role in coordination mechanisms.

- Determine the stakeholders’ potential for partnerships and engagement to help define UNHCR’s engagement and advocacy action over the course of the strategy. For this, assess the stakeholders’ interests, power and leverage to bring about the specific changes identified in the change pathways, including structural, systemic and behavioural changes. Assess the likely impact of stakeholders on UNHCR’s strategy (positive, negative, or unknown) and identify who to engage as a priority.

- Document the potential roles of stakeholders and ensure that the results framework reflects:

a. The changes UNHCR will focus on.

b. The actions and methodologies UNHCR will use to facilitate the engagement and role of these stakeholders.

Power, interest and capacity: criteria to assess the stakeholder’s potential role in a desired change

| Power and leverage | Interest | Capacity | Engagement |

| High | High | High | The stakeholder is most likely to become a partner. It may be an organization, decision-maker or opinion leader. |

| High | High | Low | The stakeholder is supported with capacity development and resources. |

| Low | High | Low/high | The stakeholder is kept informed. It might form a coalition and lobby with UNHCR to influence change. |

| High | Low | High | The stakeholder is kept informed. They can influence key audiences and allies. UNHCR is kept abreast of its positions and activities and tries to reduce any negative influence by engaging with actors who exercise influence on the stakeholder. |

Power and leverage measure the influence a stakeholder has over the change, and to what degree they can help to achieve or to block it. Interest measures to what degree the stakeholder is affected by and invested in these intended changes. Capacity can include resources, skills and assets, as well as the possibility to expand presence in targeted locations or to integrate forcibly displaced and stateless people in programmes and policies. | |||

💡 KEEP IN MIND When identifying stakeholders, be specific about each actor, such as the relevant ministry within national authorities or groups like adult women in the host community. For the sustainable response and route-based approaches, operations ask additional questions:

|

Step 4: Identify assumptions

Operations identify the key assumptions, risks and opportunities related to the desired changes and the engagement of stakeholders. Operations use the planning scenario of the strategy and iteratively help fine-tune it (see PLAN – Section 3).

If any assumptions lead to a fundamental rethink of the strategy and the theory of change, it is an indication that the operations need to reformulate the strategy, the planning scenario or the theory of change.

Examples of assumptions

❝A large proportion of the population will return to their country of origin in the next two years.❞

❝Development partner funds for reconstruction will be secured in the coming three years.❞

❝Political leaders will continue to enforce key asylum laws.❞

❝The protection environment will deteriorate over the next years❞.

💡 KEEP IN MIND When evaluating your assumptions, check them by considering the following questions:

|

Theory of change: Examples

Step 5: Review the theory of change

Once the operation has finalized the problem-cause analysis and change pathways, it is helpful to review whether the change pathway is adequately responding to the issues identified in the situation analysis and the problem-cause analysis. This assessment could include a peer review and/or verification with external actors.

Ask these questions when reviewing the theory of change:

- Is the direction/impact of the theory of change clear?

- Do the changes logically lead to the impact and the vision? Does the “if/then” logic make sense?

- Are the agents of change clearly identified?

- Do the changes address the root causes of the problems?

- Are age, gender and diversity considerations embedded?

- Are the prioritization decisions clear? Is it clear which immediate changes UNHCR will prioritize?

- Is it clear which changes we want other stakeholders to enact?

- Does the theory of change speak to UNHCR’s mandate and comparative advantage?

- Does it include change pathways for enabling sustainable responses?

- Are the assumptions clearly expressed? Are there implicit assumptions? Are there assumptions that require a redesign?

- Are the assumptions based on evidence?

UNHCR’s Policy on Age, Gender and Diversity Accountability seeks to ensure that all forcibly displaced and stateless people are put at the centre of its programmes. This aims to make sure that they fully participate in decisions that affect them and enjoy equal rights with others.

Integrating an age, gender and diversity (AGD) approach throughout the planning cycle is an organization-wide commitment. UNHCR’s strategies must present an inclusive response to the diverse needs, capacities and choices of forcibly displaced populations, promoting meaningful participation, accountability, and equitable outcomes.

The key questions for AGD considerations are:

❓ What are the measures included in the strategy for addressing the priorities, challenges, and barriers faced by those individuals with specific AGD characteristics in the forcibly displaced and stateless communities?

❓ How do these measures ensure that no one is left behind?

❓ In what way, including participatory methodologies and feedback mechanisms, do forcibly displaced and stateless people of diverse AGD characteristics participate in consultations, programmes and decision-making processes that affect them?

Operations hold preparatory briefings and brainstorming sessions on applying the AGD policy, involving the MFT or extended groups of colleagues. This helps designate AGD champions within the MFT, representing diverse functions. It is important that operations understand and analyse the results of participatory assessments.